TFC’s Distribution Days is upon us!

Next week, The Film Collaborative is holding a free virtual distribution conference, Distribution Days, which will offer concrete takeaways on the state of indie distribution and how filmmakers can navigate it. Attendees will hear from exhibitors, distributors, consultants, and filmmakers, some with case studies, as they describe and reflect on the landscape.

This conference hopes to help filmmakers develop critical thinking skills around distribution by looking at what is and what is not viable within a traditional distribution framework. It will also offer some alternative approaches. Willful blindness or a doomsday mindset are equally unproductive.

So, we are offering this pre-conference primer to set the tone, take stock of what myths are out there, and talk about what thought leaders in this space are coming up with as ways to deal with the current landscape.

Here we go!

Remember the days when creators and distributors were lying back in their easy chairs, proclaiming their satisfaction with how independent cinema has been evaluated by the marketplace? Yeah, we don’t either…and we’ve been in the industry (in the U.S.) for more than two decades. Nevertheless, there is a pervading sense that the state of independent film has never been worse—and that we’ve been going downhill from this mythic “better place” ever since Sundance was founded in 1978.

Why do we insist on bemoaning a Paradise Lost when the truth is that being a filmmaker has never been a paradise? Filmmakers have always been confronted with predatory distributors, dense and confusing contract language, onerous term lengths, noncollaborative partners, lack of transparency, and anemic support, if any (just to name a few). For an industry that prides itself on creating and shaping stories that speak to diverse audiences, we should be better at articulating truer narratives about our field.

It doesn’t help that, at Sundance this past year, all one could talk about was how streamers were “less interested in independent film than a few years ago, preferring [instead] to fund movie production internally or lean on movies that they’ve licensed” and how Sundance itself was “financially struggling, presenting fewer films than in previous years and using fewer venues.” (https://www.thewrap.com/sundance-indie-film-struggles-working-business-model) Still others like Megan Gilbride and Rebecca Green in their Dear Producer blog have put forth ideas how Sundance should be reinvented completely.

But we all know that independent film isn’t just about Sundance. We have heard a lot of discussion recently about the need to reshape the narratives we tell ourselves regarding the state of the independent film industry.

Distribution Advocates, which is also doing great work chasing the myths vs. the realities of the field, also believes that we must all question “some of our deepest-held beliefs about how independent films get made and released, and who profits from them.”

In their podcast episode about Exhibition, economist Matt Stoller remarked how “weird” it is that even with all the technology we possess connect audiences, we’re still so “atomized” that all that rises to the top is whatever appears in the algorithm Netflix chooses for us in the first few lines of key art when we log in (and we will note that even the version of the key art you see is itself based on an algorithm).

But is it really all that strange? One of the main reasons that myths exist is that someone is profiting from perpetuating them. The same with networks and platforms and algorithms. And the more layers of middlemen and gatekeepers there are, the harder it is for us to see the forest for the trees. Keeping us in our algorithmically determined silos numbs us into not minding (actually preferring) that we are watching things—or bingeing things—from the safety and comfort of our living rooms. The ability to discover on our own content that aligns with our true interests or consuming content in a communal space has disappeared the same way that the act of handwriting has…we used to be able to do it but haven’t done it in so long that it feels unnatural and too time-consuming to deal with.

Brian Newman / Sub-Genre Media acknowledges that the problems remain real, but that what everyone is calling crisis levels seems to him merely a return to norms that were in place before the bubble burst. No one, he says, is coming to rescue “independent film”—certainly not the streaming platforms, which merely used it as necessary to build a consumer base.

Many have posited myriad ideas about how to bypass the gatekeepers. Newman echoed what TFC has been recently discussion internally: that instead of many competing ideas, we need them to be merged into one bigger idea/solution. Like, for example, an overarching solution layer run by a nonprofit on top of each public exhibition avenue that will aggregate data and help filmmakers connect audiences to their content. A similar idea was also discussed at the last meeting of the Filmmaker Distribution Collective in the context of getting audiences into theaters.

By exclaiming that “No one is coming to the rescue,” Brian really means that we are all in this together, and that it’s going to take a village.

We agree, but a finer point needs to be made.

Every choice we make moving forward—whether you are a filmmaker, distributor, theater owner, or festival programmer, what have you—could possibly be distilled into either a decision for the independent filmmaking public good…or for one’s own professional interest. Saying that a non-profit should come in and offer a solution layer to aggregate data is all well and good until it threatens to put out of business someone whose livelihood is based on acquiring and trafficking in that data. How refreshing was it to be reminded at Getting Real by Mads K. Mikkelsen of CPH:DOX that his festival has no World Premiere requirements? It reminds us of the horrible posturing and gatekeeping film festivals do in the name of remaining relevant and innovative. For us to truly grow out of the predicament we are in, some of us are going to have to voluntarily release some of the controls to which we are so tightly clutching.

Keri Putnam & Barbara Twist have an excellent presentation on the progress of a dataset they are putting together of who is watching documentaries from 2017 – 2022. They provide some other data that was very sobering:

Film festivals: comparing 2019 numbers to 2023 – there was a 40% drop in attendance;

Theatrical: most docs are not released in theaters and attendance is down even for those that are released.

But they also note that there is really great work being done in the non-theatrical space— community centers, museums, libraries – that is not tracked by data. TFC’s Distribution Days offers two sessions on event theatrical and impact distribution, so we’ll be able to see a tiny bit of that data during the conference.

We also know that the educational market is still healthy, and that so many have remarked of the importance of getting young people interested in film…so we have three sessions where we hear from the Acquisitions Directors of 11 different educational distributors.

We also have a panel from folks in the EU who will provide advice on the landscape and how best to exploit films internationally and carve our rights and territories per partner. And we’ll speak to all-rights distributors about what kinds of films they see doing well, what they are doing to support filmmakers—and what their value proposition is in this marketplace.

We have a great panel on accessibility, and two others that relate to festivals and legal agreements.

Starting off with a keynote from noted distribution consultant and impact strategist Mia Bruno, the 2-day conference aims to summarize the state of the industry while providing thought provoking conversations to inspire disruption, facilitate effective collaboration, and to aid broken hearts.

Regardless of whether current days are better or worse than the heydays of Sundance and the independent film of yesteryear, Distribution Days will identify the current obstacles of the independent film distribution landscape, and what we can hold on to—as a commonality—to evolve the landscape together in the future.

If you look a little deeper, you will see that, despite all the challenges, filmmakers have and can still achieve “success” when they understand the terrain, (sometimes) work with multiple partners with a bifurcated strategy, protect themselves contractually, and maintain and grow their own personal audience.

We hope you will join us. And for those of you that cannot make all of the sessions we are offering live on May 2 & 3, you’ll be able to catch up on what you missed via The Film Collaborative website after the conference is over.

We look forward to seeing you next week! And if you have not registered yet, you can do so for free at this link.

David Averbach April 25th, 2024

Posted In: case studies, Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, education, Film Festivals, International Sales, Legal, Marketing, Theatrical

All About AVOD? part 1: What To Do with Your Library Title

by David Averbach and Orly Ravid

One of the joys of working at The Film Collaborative is our extended filmmaker family. Some of the filmmakers we work with we have known for decades, back to when they made their first films. Inevitably, after seven-, ten-, or twelve-year terms, many of these filmmakers are getting their rights back from the distributors with whom they originally entered distribution deals.

They often ask us, “What is possible for my film now? What can I do to give it a second life?”

(We should state that the vast majority of these filmmakers do not have obviously commercial projects that could simply be offered to a different large streaming service like Netflix or Hulu. They are the type of films that TFC handles: solid films with good or at least decent festival pedigrees and proper distribution at the time of their initial release.)

Unfortunately, there is no one answer for every film. Nor is there a fixed answer for each type of film, as platforms’ needs can change at the drop of a hat. Except that all platforms seem to have an endless appetite for true crime docs, but we digress…

So, this blog article is less of a “how to” for library titles, and more of a “how to think” about them.

Certainly, there are non-exclusive subscription-based (SVOD) platforms that align with various content areas, such as Documentary+, Topic, Wondrium, Curiosity Stream, Coda, Qello, Tastemade, Gaia, Revry, and many more (check out our Digital Distribution Guide for more info). These are platforms that offer a revenue share based on minutes watched. Since they may have not been in existence when the filmmakers’ original distribution deals were arranged, they are definitely worth exploring when one (or more) of them is a fit for your project.

But there are also ad-supported (AVOD) platforms1, which are free to the end user and rely on commercials that play before the film starts. Generally speaking, AVOD platforms seem to be more lucrative in terms of revenue than specialized SVOD platforms, and we’ve heard that some films are making “real” money them (more on that later). While there’s no guarantee that AVOD platforms will bring in more money than SVOD platforms, or much money at all, this at least makes sense, anecdotally: with the rise in commercial streaming services and especially since the start of the pandemic, folks are watching increasingly more content, but actually spending less above and beyond the Netflix/Amazon Prime/HBO/Disney etc. combination of platforms that they have ostensibly come to view as basic utilities.2 So AVOD provides a win-win for platforms and consumers alike.

Until recently, filmmakers have been somewhat reluctant to place their films on AVOD platforms, but they are coming to realize what distributors have known for a few years now—that AVOD can continue to bring in revenue when transactional platforms such as iTunes are no longer performing for a film the way they might have at the beginning of their digital run.

So, we set out to ask what we believed was a simple question: which AVOD platforms are taking which type of library content? The Film Collaborative has some limited experience with AVOD platforms, but we felt it prudent to talk to some folks that do this day in and day out. To that end, we reached out to Nick Savva, Vice President of Content Distribution at Giant Pictures, and Tristan Gregson, Director of Licensing & Distribution at BitMAX.

The answer turns out to be a complicated one. Here’s why:

Most AVOD platforms are looking for all kinds of content. One of the trends that has been occurring for the past few years is the addition of new platforms, not just in the U.S., but globally. And the pandemic has accelerated existing trends, so there are even more new platforms than ever. These platforms are not going to be able to produce or acquire enough new content to justify their existence, so they rely on library titles as much as they do new releases. So, the good news is that there are more outlets and revenue opportunities for library titles than ever.

The not-so-great news is that sometimes AVOD platforms are actually looking for specific types of films, but only for a limited time to fill a specific need. Platforms have a good sense of what percentage of their films are, for example, comedies, dramas, thrillers, horror, documentaries, true crime, etc. When they look at who is watching what, if comedies are overperforming on the platform relative to the percentage of titles they occupy overall, the platform may not take as many comedies for a while until that changes, or they could decide to double down and take more comedies at the expense of other types of films. Conversely, if there is a category that is underperforming, they could decide that they need some fresh meat in that category, or simply decide to take less of it.3

So why exactly is this bad news? Because as the needs of AVOD platforms ebb and flow, the entities with the best chance of succeeding are those that can respond quickly to calls from these platforms for specific content. A high percentage of the work Giant Pictures does with AVOD platforms involves their distributor clients, who use Giant as a sort of white label service. Giant is tasked with placing their content libraries on these platforms because these distributors don’t have the bandwidth to keep up with which platforms want what from month to month. Similarly, BitMAX works with many studios to deliver to these platforms, but the studios are the ones handling the licensing. What this means is that the bulk of content going to AVOD platforms is coming from the content libraries of studios and distributors. That is not to say that films from individual filmmakers aren’t being placed on AVOD platforms by Giant/BitMAX, it’s just that studios and distributors are their go-to sources for content because they can provide a bunch of titles with a quick turnaround.

The sad reality here is that AVOD is one area of distribution where middlemen are being added to the mix in a way that makes it harder for individual filmmakers to take back control of their films.

Many of the filmmakers who have just gotten their rights back often remark to us how glad they are to have done so, as if they are finally getting out of a bad marriage. Even if the relationship wasn’t such a badmarriage, this sentiment—justified or not—perhaps stems from the fact that their TVOD sales had dropped over the years and they felt like their distributor was no longer doing anything for their film, or that they were tired of not receiving reporting because there were long periods of time with no earnings. The last thing they appear to want to do is start up a new relationship with a new distributor or aggregator and incur more encoding costs for a shot in the dark in terms of being accepted by these platforms only to earn $12 a quarter in earnings.

It’s important to really have a look at the reporting your old distributor provided you. There’s a good chance that simply re-creating what your old distributor did—perhaps your film was already on AVOD platforms—is going to give you a completely different outcome. But to the extent that your project has not been tested in the current landscape, what should a filmmaker be thinking about if they find themselves in the position of deciding whether to go it alone or offer their film to another distributor?

It’s Your Time and Money

Bandwidth:

Tristan Gregson remarked that the same rules apply for library titles as when just starting out, and his stance was the following: if you know how to engage your audience then put it somewhere. If not, then don’t. Whether you try to go it on your own or partner with another distributor, unless there is someone that’s going to remind your audience that it’s there, there’s a good chance your film will sit unnoticed in a glut of content. This is going to take some effort and while a new distributor might do a bit of marketing, you are going to have to get creative. Perhaps time the re-release of this older film with a new project of yours?

Cost:

If you go through an aggregator like BitMAX, you are probably looking at a bare minimum of $2,000 for encoding, QC, and delivery and to pitch and deliver to a few SVOD or AVOD platforms. It’s a fee for service, so they will be hands off when it comes to strategy, and uninvolved when it comes to your earnings. If a distributor like Giant Pictures is willing to work with you, it can cost twice that much, but they will be real partners in the sense that they will be proactive in helping you come up with a strategy. They will also take a certain percentage of your earnings. You may also be able to negotiate lower encoding costs in exchange for an increased percentage of your earnings.

What is in it for the Platform?

Metrics:

Nick Savva advises filmmakers to think about your film like a platform would: what are your film’s metrics? These scores can tell a lot about the public’s level of familiarity with your film, and there are data tracking services that distributors and platforms use to determine them. Also among the first things that an acquisitions team would look at would be indications of basic audience awareness, such as the of the number of positive reviews on Amazon, or the ratings on IMDb. If the metrics are good, a deal might be attractive to a platform. Are there any recent reviews? In other words, does your film still hold up?

Is there one Platform that is better for my film than others?

Honestly, there are not all that many AVOD platforms in the U.S. Tubi, Pluto, Roku, Peacock, IMDb TV, and a few others. The good thing about AVOD is that most deals are non-exclusive, meaning that you can be on more than one at once. But should you apply for all of them? How does one decide?

Signal Boost:

The following might not be possible for every film, but, if possible, try to think about the likely television habits of your audience and the specifics of each platform and take advantage of the free signal boost.

People are very familiar with platforms like Netflix and Hulu, but when it comes to platforms like Tubi or Pluto, why would one choose to watch one over the other? The answer might be simpler than you would think!

Does your film have a TV star in it? If they are on the FOX network, chances are that audiences will see ads for Tubi, because Fox is the parent company of Tubi. If they are on NBC, then perhaps Peacock or Xumo will be advertised.

There are also tricks that might apply for documentaries too. Pluto just became available in Latin America and Mexico, so films with Latinx content might want to consider that platform first.

One of The Film Collaborative’s digital distribution titles, The Green Girl, has been doing extremely well on Pluto, but not so well on Tubi or Roku, and for the longest time we couldn’t figure out why. Then it hit us: this documentary is about an actress who famously appeared on the 1960s television show Star Trek. Since Pluto is owned by Viacom, which is the parent company of Paramount, Pluto is the AVOD destination platform for Trekkies!

Keywords:

Make sure your keyword game is strong. Aggregators and distributors will ask you to fill out a metadata sheet with genres/keywords, but you must make sure the choices conform to actual categories and genres on the platforms, which can differ from one another and evolve over time. Distributors have even admitted that it’s hard for them to keep up sometimes, especially if such metadata is capture via web interface. Case in point: The Film Collaborative placed a few films we have been working with for years onto Tubi, but the keywords that we chose when we first submitted the film to our aggregator were based on iTunes genres, which are very narrow. Cut to the films getting up onto Tubi, and they were almost impossible to find without searching for their exact titles. It’s been several months, and we are still struggling, with the help of our aggregator, to get these updated on the platform. Bottom line is that it’s important to be familiar with each platform and know how one might best search for your film and be proactive to ensure that the proper information is being delivered to each platform at the time of delivery.

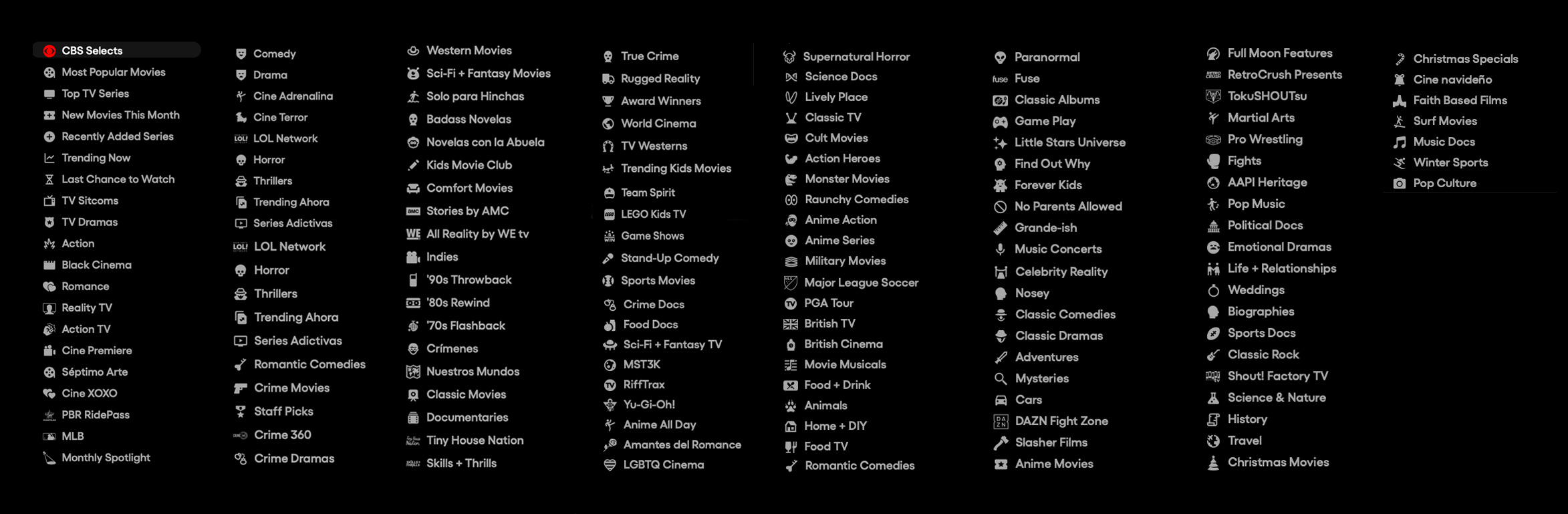

Pluto TV (owned by CBS/Viacom) offers a dizzying array of genres/categories to choose from (they appear in a vertical sidebar and seem to rearrange themselves periodically)

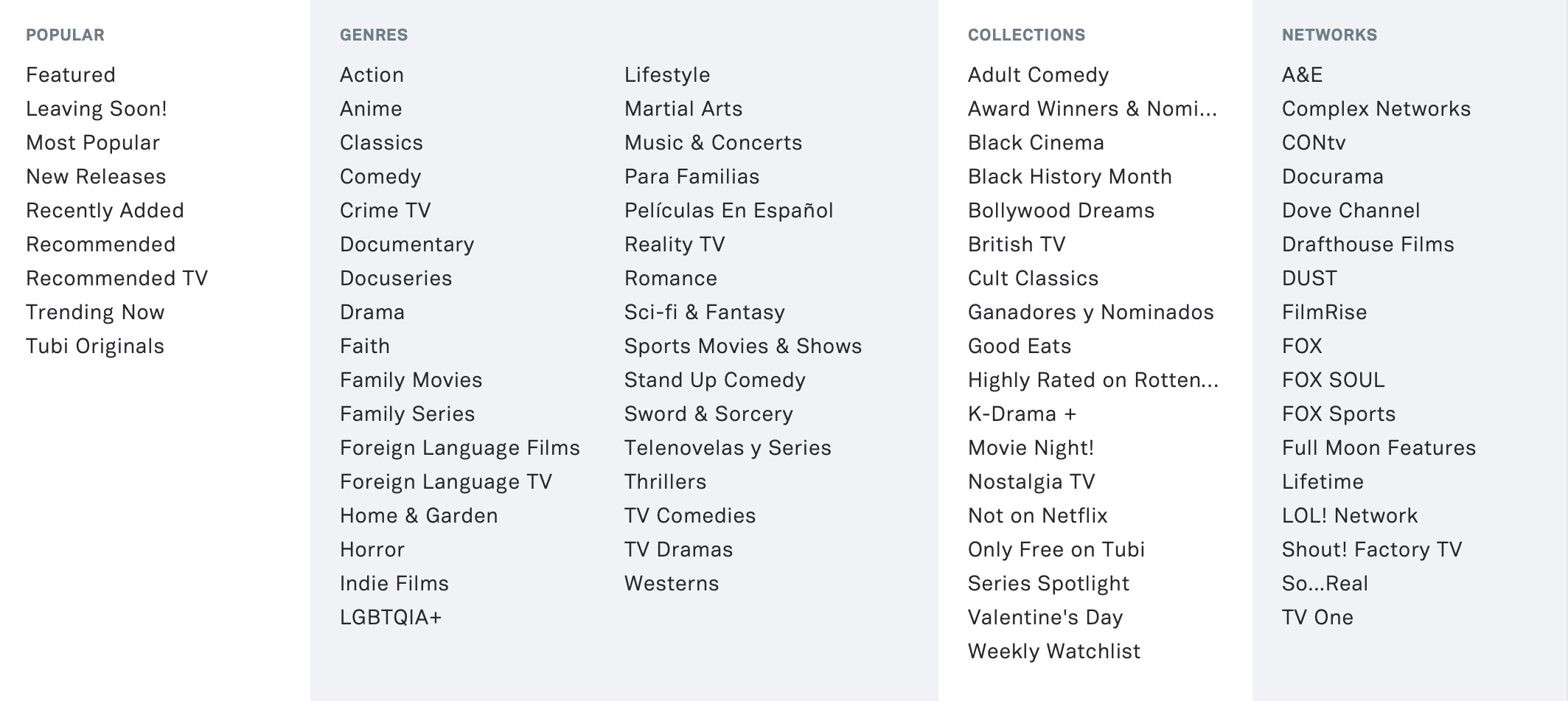

Tubi’s current “Browse” navigation tab. Tubi’s parent company is Fox Corporation.

Very Mini Library Titles Case Study

We talked to director/producer Kim Furst, whose rights to her 2014 film Flying the Feathered Edge: The Bob Hoover Project came back to her after her aggregator (Juice) declined to renew the term. She expressed that she did not want to use another aggregator like Distribber/Quiver/Bitmax/FilmHub because there was a concern that they might not be around in another 5 years. (As you probably are aware, Distribber has shuttered, and Quiver is not currently accepting films from individual filmmakers and will probably turn into something else).

So, she went with Giant Pictures.

The cost to re-encode was about $4K. While she did not feel great about having to shell out such a huge chunk of cash on a library title, Kim still felt that the film still had life in it, and she wanted to try other distribution avenues, such as public television, that she never managed to do when the film originally came out.

We should note that one of the reasons why Giant might have been interested in the film was that it is narrated by Harrison Ford. The film is about Bob Hoover, an American fighter pilot and air show aviator, and Ford has a longstanding love of flying planes. So, there is some commercial appeal that can be leveraged here.

She is at the stage where they have initiated the re-release. Right now, the film is back up on TVOD platforms, including being re-placed on Amazon, which Giant was able to accomplish despite the platform’s embargo on unsolicited non-fiction content.

We asked Kim to report back on what happens next. We suggested that she note where all of Harrison Ford’s top movies are on AVOD and take note if that platform sees any boost from the connection.

Revenue Range

With so many variables and permutations, it’s hard to give a real range in terms of what’s possible for a library title on AVOD, especially since it’s impossible to know when we are talking about the revenue of a “library” title—as opposed to that of a title that enters AVOD as part of their “new release” window.

When I asked Tristan about revenue, he acknowledged that to even talk about it would put us into “anecdotal space,” because he isn’t aware of what it took for some of his clients to earn, for example, 5 figures during an AVOD revenue period, as compared with other clients who were only able to earn, say, 3 figures. While he admitted that he has seen a single independent film title clear quite a bit, he also reiterated to me that at a certain point of revenue generation, distributors tend to get involved with a title to signal boost, so it isn’t exactly “a fair comparison to those independents working day in and day out to make a few grand on their title. But if the message is that you don’t have to be working with one of the major studios to reach seven figures in revenue, it can still very much be accomplished in this current age of VOD releasing.”

Nick spoke more specifically to AVOD, noting that they “have had a couple of indie titles which have generated $100k+ royalties in 1 month on 1 AVOD platform. But, of course, those are outliers.”

One of our filmmakers told us that they have two filmmaker friends-of-friends (whose films deal with Black Cinema content) for whom Tubi is paying well: one reported $15K a month in residuals while the other one says they are making $4-6K a month on a movie released 10 years ago. Both filmmakers allegedly went through an aggregator, but their friend said they were reluctant to allow the names of their respective films to be shared publicly.

So, as Tristan remarked, it’s best not to hold too tightly onto evidence that is merely anecdotal, because TFC certainly knows films that are making almost nothing on AVOD.

Notes:

1. As we were conceiving this article on Library titles, and realizing how important AVOD could be for an older title, Tiffany Pritchard of Filmmaker Magazine approached us about an article she and Scott Macaulay were writing about AVOD. Its title is Commercial Breaks and it is available in the January 2022 issue of the magazine (behind paywall, at least for now).

2. As a reference, this article discusses how shorter theatrical windows might be accelerating TVOD decline and shows the increase in both spending and subscription stream share from 2019 to 2021. Others, however, predict that streaming services will lose a lot of subscribers in 2022. Still, it’s hard to know how streaming services are faring, as many of them are not transparent in their total number of subscribers and average revenue per year.

3. Stephen Follows assembled a team, called VOD Clickstream, that uses clickstream data to analyze viewing patterns on Netflix between January 2016 and June 2019. He also offers a ton of information on his website. In November 2020, he presented a talk entitled, “Calculating What Types of Film and TV Content Perform Best on SVOD?”, in which he outlined how he believed Netflix navigates how popular a genre is versus what percentage of content of that genre is available on the platform.

David Averbach February 8th, 2022

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, Documentaries, technology

UPDATED: A Practical Guide to Distributing Your Film Internationally: Who Else is Out There in the International Digital Space Beyond the Global “Big Guns”?

Guest blog post by Wendy Bernfeld

Note: This article was originally published in May, 2020. We are updating it as of March 2021, since things continue to evolve at lightning speed in the digital sector. All March 2021 updates will be in red.

The ongoing mission of TFC’s Digital Distribution Guide is to list every platform one could possibly or reasonably be on. It’s a very ambitious list, but not necessarily exhaustive because there are thousands of tiny or not completely reputable platforms (and, conversely, channels with non-linear versions of their broadcasts on VOD) that we have chosen not to include, but striving as much as possible to list the most credible or key platforms where one’s film could possibly be.

But which platforms are actually good targets for arthouse film, especially the kinds of indie content that TFC normal handles, that pay enough money to potentially make sense in an international hybrid distribution strategy? And how do we look at the platforms and film sales in general in light of the “new normal” that we’re all in?

For this, we could think of no better person to ask than our dear friend and colleague Wendy Bernfeld, Founder and Managing Director of Rights Stuff and co-author of our second case study book in 2014 Selling Your Film Outside the U.S. (free on Amazon Kindle and Apple iBooks). Wendy specializes in Library and Original Content acquisition/distribution, international strategy / deal advice, for traditional media (film, TV, pay TV), digital media (Internet/IPTV, VOD, mobile, OTT/devices), and web/cross-platform/transmedia programming, and also active on various film festival / advisory boards, such as IDFA, Binger Film Institute, Seize the Night, Outdoor FilmFest, and others, including TFC! Follow her on Twitter: @wbernfeld. So without further ado, here is Wendy’s update:

For this, we could think of no better person to ask than our dear friend and colleague Wendy Bernfeld, Founder and Managing Director of Rights Stuff and co-author of our second case study book in 2014 Selling Your Film Outside the U.S. (free on Amazon Kindle and Apple iBooks). Wendy specializes in Library and Original Content acquisition/distribution, international strategy / deal advice, for traditional media (film, TV, pay TV), digital media (Internet/IPTV, VOD, mobile, OTT/devices), and web/cross-platform/transmedia programming, and also active on various film festival / advisory boards, such as IDFA, Binger Film Institute, Seize the Night, Outdoor FilmFest, and others, including TFC! Follow her on Twitter: @wbernfeld. So without further ado, here is Wendy’s update:

I’m not a distributor or sales agent, taking IP, but rather, a digital sector consultant. Most of the time I’m a buyer/biz dev exec for platforms, often before they launch, or afterwards when they roll out into new regions, genres, and biz models. The rest of the time I’m on your side of the table, helping rightsholders/producers/sales agents/festivals deal beyond the usual suspects.

Since my last TFC blog on the topic, the platform-buying sector has continued to grow and by now explode—particularly in SVOD and AVOD, along with a more recent upsurge in TVOD variations and innovations driven by COVID-19 (Premium VOD, virtual cinema, and festivals, both online and hybrid)u.

Explosion in the VOD Sector Pre Covid-19

This explosion came from various sources:

- the competitive appetites of mainstream “Big Guns,” i.e. Netflix, Amazon and now, the newer USA entrants, such as HBOMax, AppleTV+, Disney+/Hulu, Peacock, Viacom/CBS in SVOD, and Pluto.tv, TubiTV, Roku.tv in AVOD (most of which will also roll out internationally in 2020-21);

- Overseas demand from the scores of EMEA/International sector regional and multiregional VODs (via telecom, cable, OTT, TV networks, cinemas and consumer electronics types) who strive to be ‘head on’ competitors;

- and a wealth of complementary VODs, drilling down into a specific theme, genre, or niche target audience, which are lower-priced and positioning themselves as “stackable” add-ons for the household.

The beauty is, beyond the Global Big Guns, most of the VODs still license titles non-exclusively, so one can sell across multiple windows and regions, through TVOD, SVOD, and AVOD, balanced with traditional.

Although some of the earlier indie film and doc services sadly fell away since the last blog, more have stabilized, morphed, and matured.

- Some arthouse SVOD sites (Mubi.com, UniversCine and FilmIn Spain for example) have been around for more than a decade. Other new entrants have found a foothold, although are still in early days (e.g. Cinetree).

- Some were already credibly funding or co-funding Originals (Movistar+, FilmIn, Viaplay, Stan, Curiosity Stream).

- Others either went deeper into niches, or expanded to wider regions, (e.g. American sites adding international regions, or vice versa), and/or added more genres of buying, and/or added other business models—hybrids in TVOD, SVOD, and AVOD). Examples of these include Rakuten, Mubi, UniversCine/Uncut, All4/WalterPresents, SundanceNow/Shudder, and Acorn.tv.

Already, before the advent of COVID-19, the ‘Holy Grail’ of a Netflix or Amazon deal was increasingly challenging for most indies, since, in general:

- more focus was on platform Originals, and/or Series (rather than feature films or docs);

- and for features, more focus was on stars/recognition rather than niche films.

- Non-USA films became a bigger priority, as the platforms intensified EMEA and international localization and had to deal with regulatory/political content requirements (e.g. airtime and funding).

Thus, it had already been critical for indies to go beyond the Big Guns to see who else was out there abroad, buying and sometimes funding.

Since COVID-19

It is no surprise that audiences in lockdown globally have caused a dramatic surge in VOD/TV viewing. With production halted, and festivals and cinemas closed or morphing online, the platforms and networks have been rapidly running through their inventories. As an upside, domestically and abroad, more platforms are now more open to wider types of buying than before, including an enhanced appetite for festival, indie films, and docs.

“Big Guns”

Even the largest and mainstream players are turning now to select curated library and classics – for example, in recent weeks Netflix licensed packages of French/other auteur classics from MK2 France.

Assume for the moment you are in the lucky position to have interest in your film from a global Netflix or Amazon Prime type, from which the highest-priced deals can result. However, along with it comes restrictive exclusivity and various other window holdbacks. Heavier personal marketing is required to help viewers find your film and hear your message (assuming that is important to you, rather than just the large license fees).

As before, keep in mind the domestic deal offerings are one price tag, but do you agree to automatically tack on “ROW” (rest of world) to the domestic deal offer? Certainly easier and where the deal is non-exclusive, also an easier call—but if exclusivity is required, now more than ever it is key, if your film is in hot demand, to consider international possibilities/valuation from these competitors and complementary sites abroad, across different regions, multiple platforms, and successive windows.

That strategy, if you choose to follow it, is WAY more work, as there are a dizzying array of opportunities to explore. However, if you are willing to take the time and effort – whether directly, or via your agents or a combination (hybrid) of digital and traditional reps—to go beyond the usual suspects, you achieve a new pipeline for the longer term. At the very least, the intel from the patchwork of offers allows for better negotiation of the ROW deal requested back home.

Netflix has quietly and significantly launched a linear version of its SVOD service to SVOD subscribers in France. If this interesting trial (sort of like an ‘everything old is new again’ experiment) goes well, Netflix may well expand this linear programming approach to other regions. There is awareness particularly in some countries that consumers may be struggling with too many choices and would prefer to ‘lean back’ on a more curated programming experience that includes scheduled linear viewing, etc…and on a related note, some other SVODs, such as Docubay in India, have also launched a linear option for their viewers/subscribers. Let’s watch this space!

Netflix also announced recently in January that it will focus on premiering one new feature film per week (as opposed to earlier, where there was more of an emphasis on series originals).

As of late February 2021, Amazon just suddenly shut off ‘short form content’ and ‘documentaries’ from the self-upload Prime Video Direct program, causing great concern in the industry as to the fate of indie docs that are ‘unsolicited.’ We are looking into whether this also applies to distributors, aggregators, and other sources, as well.

TVOD sector: and newer festival streaming, PVOD, virtual cinema

The COVID-19 era has, on the plus side, mobilized the industry to break away from traditional assumptions and has rapidly sparked innovation (particularly in historic approaches to film distribution) for new releases.

Innovations: Although beyond the scope of this blog to detail this, I’ll note my KUDOS to the film industry in the face of these challenging times, for the recent resurgence in TVOD and related innovations borne out of COVID-19:

- Festival Streaming: Festivals/markets that were cancelled are moving commercially and creatively online (e.g. New Zealand International Film Fest)

- Premium TVOD:

in lieu of cinema exhibition, some films are going straight to platforms (e.g. Never Rarely Sometimes Always, etc.)Although HBO Max and various other U.S.-based platforms are skipping theatrical and going straight to VOD releases—a sore point for some indie filmmakers in the U.S.—one should note that for HBO Europe, this is not expected to be the case until later in 2021 because HBO Max is not available yet in Europe. The first region in 2021 that HBO Max will launch internationally in will be Latin America. HBO Europe will still continue as it is until later this year. - Virtual Cinema: in lieu of Theatrical, releasing Currents/events online and sharing revenues with Cinemas (e.g. ModernFilm UK, KinowMarquee USA,) and other innovations like Drive-ins! (Vilnius airport!)

All require open, nimble and flexible thinking, balancing traditional and digital sector audiences and stakeholders, windows, revenues, and marketing—all at lightning speed.

There is no doubt in my mind that some of these will continue, at least in modified form, post COVID-19…although we all acknowledge there is no total substitute for the cinema experience and in-person contact.

Traditional TVOD: For current and library titles, usually nonexclusive, and on rev share, the windows and strategies remain largely unchanged from our earlier blogs:

- DON’T STOP AT ONE DEAL – i.e. if doing an iTunes or similar TVOD deal, try to also go to as many of the rest out there that you can,

- Including TVODs from cinema-related chains (e.g. PatheThuis NL), telecoms/cable (e.g. Vodafone/Ziggo, Orange) PayTV and Free TV (e.g. Sky, RTL, All4, UniversCine, etc.),

- across many regions, and mainstream and niche/theme sites so the revenues (and marketing buzz) cumulates.

SVOD/AVOD Internationally

The PayTV/SVOD sector is still where most of the revenues for filmmakers arise. For library deals, usually the sweet spot for SVOD is for films 2-5 years old, and AVOD is usually older.

Although there are in theory over 3000 VOD platforms in the EU alone (not even considering the rest of the world), at Rights Stuff, we tend to focus on a curated fraction, e.g. those 50-100 that are reputable, and yet also commercial, paying proper flat license fees (the usual for SVOD/AVOD and ‘multimodel’ sites).

Of course, there are some exceptions where flat fees/MG’s are less customary or needed due to platform size/scale (such as for the larger USA sites like Hulu, Amazon, Tubi.tv, Pluto.tv). However, as a general rule in EMEA/international, one needs something more than a rev share in smaller SVODs and AVOD.

Platform Examples (a non-exhaustive list for Indie Films and Docs)

Below is a snapshot list of some examples of platforms (whether mainstream, or thematic: i.e. niche/genre specific) beyond USA. These have recently bought and are open to buying quality indie films, art house, or docs from USA indies, usually with some festival or other high acclaim – without necessarily having local EU releases, language versions, or big stars (although the latter helps elevate the appetite and deal size).

CAVEATS: This list is NOT exhaustive, but an illustrative snapshot at this time. There are many more, not listed below, including mainstream or very local language sites, or those in various niches not usually of immediate interest to TFC filmmakers.

To help bring it down to earth, I’ve used as one criteria: they have done a deal with a niche indie/doc filmmaker from the USA in the recent past.

Also keep in mind:

- Platforms tastes, needs, and appetites (and competitive positioning) are always changing.

- So, on the plus side, even if a title is rejected now, one can circle back 6 months later (if the rejection reason was more that the platform was overstocked in a category or bad budget timing).

- But obviously do not circle back if they rejected the film because they didn’t like it/not suitable for them.

- Your film benefits most overseas if it travels well culturally, has strong acclaim, or is particularly topical and/or other marketable appeal.

- Language is very relevant but does not have to be a barrier:

- English OV films generally travel easiest first to other English regions/sites (Canada, UK, IE, AU, NZ, South Africa);

- then next easiest, is subtitling-friendly regions (like Nordic, Benelux) as well as the pure cinephile arthouse and documentary sites (where audiences are accustomed to subtitles);

- In other regions such as Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and Brazil, dubbing requirements have to be factored in. That said, if you have a few potentially interested platforms in one region/language, it is easier to assess value of dubbing costs—no need to do in advance.

- Politically: USA films are, frankly, not at the top of some EU platform priorities at the moment – so be realistic in your expectations.

- For example, EU platforms now have content country of origin quotas (official and unofficial) to balance, ranging from 20-50% in practice.

- This means after a platform has first bought its MPAA studio major output deals (if applicable), and then bought from its own EU or local minimajor and indie distributors, and then bought its own direct local indie filmmakers, then and only then can they have room for ad hoc cherrypicked USA indie sector films.

Caveats aside: Let’s look at some platforms who have, despite the above, bought USA indies selectively in recent past. The thematics (niches) are usually listed first, as sales to mainstreamers are less frequent (but some are still listed).

Regions

UK/Ireland

Niche

| Mubi | ||

|

curated art house | Multiregion • SVOD, some TVOD | Expanded most recently to India and ever-innovating, such as with its MubiGo cinema cross-marketing initiatives and its “Day and Date” or other theatrical partnerships with UK indie art cinemas. Expanded beyond merely day-and-date to include “virtual cinema” offerings. Mubi has also expanded their library, and expanded to more regions as well. |

| Curzon | ||

|

arthouse | date and date TVOD | Expanded beyond mere day-and-date to include “virtual cinema” offerings. |

| AMC’s Sundance Now | ||

|

indie series | SVOD | Has expanded beyond North America to the UK and Ireland |

| Shudder | ||

|

horror | UK, USA, some other EU • SVOD | Has moved also into Ireland, Australia, and New Zealand. Later in 2020 it started funding Originals. |

| Docsville | ||

|

docs | UK | Nick Fraser (ex BBC Storyville). Although still live online hasn’t been actively buying or funding lately, unfortunately. We’ll watch this space as it morphs through different reorganization/investment stages. |

| Acorn.tv | ||

|

British | USA, UK • SVOD | Content that features British and English colonies, some exceptions. AcornTV has expanded beyond the U.S. and UK to also include Canada, Latin America, Spain, Australia, New Zealand, the Nordics, the Netherlands and South Africa. They also have been funding some Originals again. They are positioning themselves against the competitors in the Brit/Anglo space—such as BritBOX (BBC, ITV, Channel4) and are buying from wider sources and regions to differentiate themselves. |

More Mainstream

| All4 | ||

|

occasional indie titles | multimodel | All4 / Film4 / Channel4 |

| Walter Presents | ||

|

episodic | SVOD, AVOD | Walter Presents is mainly focused on episodic from outside UK, not films or docs. Channel 4’s Walter Presents series SVOD/AVOD has expanded regions beyond UK, Ireland, the U.S., and Australia to Belgium, Italy and New Zealand, as well. |

| NowTV by Sky | ||

|

mainstream | PAY/SVOD/TVOD | BSkyB/Sky/SkyNow. Rare, unless there is a location connection/rep/acclaim/release |

| Discovery+ | ||

|

mainstream | SVOD | Now launched in the UK |

Australia/New Zealand

Niche

| iwonder | ||

|

docs | SVOD, AVOD • AU, NZ, Southest Asia | in 2020, iwonder also funded an Original during the pandemic that may be a one-off or may be followed by more, but it is still an interesting development for creators when buyers start to get involved in funding…we’ll watch this space. |

| SBS World Movies Network | ||

|

world cinema | AVOD and TV • Australia | AVOD arm of SBS TV / VOD. SBS World Movies is now only AVOD and TV, not SVOD anymore. They still focus on films from outside Australia (world cinema and foreign language cinema). |

More Mainstream

| Stan | ||

|

mainstream | SVOD • Australia | Channel 9’s SVOD. Stan SVOD in Australia has greatly increased both its number of subscribers and its competitive position, and continues to fund Originals. In early 2021, Stan announced a partnership with Walter Presents for an expanded drama slate. |

| Neon | ||

|

mainstream | SVOD • New Zealand | merging with competitor Lightbox. New Zealand’s Neon and Lightbox services have merged into one SVOD, still called Neon, run by parent Sky New Zealand. Neon is not to be confused with the Neon (Neon Rated) distributor in the U.S. |

| Lightbox | ||

|

mainstream | SVOD • New Zealand | merging with competitor Neon. New Zealand’s Neon and Lightbox services have merged into one SVOD, called Neon, run by parent Sky New Zealand. |

Benelux

Niche

| Cinetree | ||

|

SVOD/TVOD • The Netherlands | |

| Uncut | ||

|

PVOD/Virtual Cinema/SVOD/TVOD • Benelux | Uncut and Universciné have merged their SVOD offerings and rebranded into a new hybrid Benelux (Belgium, Luxembourg, the Netherlands) service called “Sooner,” which is also in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland. They also have been active in select virtual cinema offerings. | |

| Universciné | ||

|

PVOD/Virtual Cinema/SVOD/TVOD • Belgium | Uncut and Universciné have merged into a new hybrid SVOD service called “Sooner” (see Uncut, above, and Sooner, below). | |

| Sooner | ||

|

SVOD | Uncut and Universciné have merged into this new hybrid SVOD service in Belgium, Luxembourg, The Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (see UniversCiné and Uncut, above). | |

| OutTV | ||

|

LGBTQ | SVOD •The Netherlands | (separate from OUTtv in Canada). OutTV in the Netherlands (not to be confused with OUTtv in Canada) has expanded to wider regions (Benelux, Sweden, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Israel, Spain, and Central/Eastern Europe.) The platform owners of OutTV in The Netherlands have also bought Cinemien, the local art house Benelux distributor, and will be consolidating offerings in platforms and content licensing in future. Watch this space. |

More Mainstream

| Proximus | ||

|

TVOD/SVOD • Belgium | |

| RTLs4 / Videoland | ||

|

multimodel | TVOD/SVOD/AVOD and TV • The Netherlands | Also funding (local) Originals |

| Movies & Series | ||

|

SVOD/TVOD • The Netherlands | from Vodafone/Ziggo | |

| Film1 (SPI International) | ||

|

PAY/SVOD • The Netherlands | now part of Central Eastern Europe/UK-related SPI International sites Filmbox and Filmbox Arthouse | |

| Pathé Thius | ||

|

TVOD • The Netherlands | complementary spinoff Pathé brand cinemas in the Netherlands. Pathe Thuis in The Netherlands funded its first original. An interesting development from ‘mere’ buyer to now funder. | |

| NPO+ | ||

|

Dutch public broadcasting | SVOD • The Netherlands | only occasional non-Dutch buying |

Spain

Niche

| FilmIn | ||

|

SVOD, some TVOD | Spain/Mexico/Portugal. Also now funding select Originals. | |

| Planet Horror | ||

|

horror | SVOD | via AMC |

More Mainstream

| Movistar (Telefonica) | ||

|

PAY/SVOD | Spain / Latin America | |

| Rakuten (formerly Wuaki.tv) | ||

|

multimodel | Spain, Beneflux, other EU. Rakuten expanded its focus beyond SVOD, TVOD, to increased AVOD/OTT offerings (e.g., via connected TVs), and has funded a few Originals in more mainstream categories (previously, it had been ‘merely’ a buyer). |

France

Niche

| FilmoTV | ||

|

arthouse | SVOD |

| Universcine | ||

|

TVOD/SVOD | |

| Trace.tv / TracePlay | ||

|

SVOD | Afro.urban theme, millennials, also in UK, Africa/global diaspora | |

| La Cinetek | ||

|

SVOD | |

| Tenk | ||

|

docs | SVOD | TENK docs SVOD is in France, Belgium, Switzerland, Luxembourg, and (most recently) Quebec in Canada. |

More Mainstream

| Pluto.tv | ||

|

AVOD | France, Germany, US (now part of Viacom). Pluto AVOD (part of Viacom group) expanded to more regions, beyond Germany, U.S. and France to also include Latin America, Spain, Canada, the UK, and Brazil. It is expected to launch in Italy later in 2021. | |

| Orange, OCS | ||

|

multimodel | mainstream multimodel but also selective higher-end arthouse and indies | |

| MyCanal | ||

|

SVOD | CanalPlay SVOD has been discontinued, but they still offer CanalSERIES, which, in addition to France, has also since expanded to Poland. |

Nordics

Niche

| Curio | ||

|

docs | SVOD |

| Dplay | ||

|

docs | SVOD/AVOD | via Discovery Network. DPLAY SVOD has expanded to more regions, and also its new service brand variation SVOD, Discovery+, in the UK. |

More Mainstream

| Viaplay / Viafree | ||

|

TVOD/SVOD/AVOD and PAY/FREE | usually mainstream, and local, but some indie buying from abroad. Viaplay Nordics (SVOD and multimodel) announced a launch in the U.S. (and also in the Baltics, later in 2021). This will amount to a high volume of Originals deals and coproductions (digital) with other players, including series producers in the U.S. and Canada. | |

| Cmore | ||

|

PAY/SVOD | |

| HBO Europe | ||

|

PAY/SVOD | Central Eastern Europe, Nordics, Spain, Portugal. HBO Europe remains for the time being, as it is not yet the full-on HBO MAX that the U.S. is offering. As noted above, HBO Max’s first international launch will be in Latin America, and then other regions in the EU will follow later in 2021. |

Germany

Niche

| Realeyz+ | ||

|

SVOD/TVOD and broader OTT | |

| Flimmit | ||

|

SVOD | Austria. Removing this from the active interest selling list for U.S. indies, as their programming model has recently narrowed/intensified to films specific to the Austrian region rather than from wider sources abroad. They are very active and good quality but not buying (much) in terms of U.S. indies these days. |

More Mainstream

| Joyn / Joyn Plus | ||

|

SVOD/TVOD and broader OTT | Germany. Maxdome is merging into it. Joyn+ SVOD has begun funding German Originals, not just ‘buying.’ |

Central Eastern Europe / Middle East / Russia

Niche

| Filmbox / Filmbox Arthouse | ||

|

PAY/SVOD | Central Eastern Europe, UK. Filmbox Live has now evolved as of Feb. 2021 to Filmbox+, replacing FilmBox Extra and expanding their service offerings in content (film, docs, etc.) and tech variations (apps, channel). Filmbox ArtHouse continues, as do other thematic channel strands. |

More Mainstream

| StarzPlay Arabia | ||

|

SVOD | StarzPlay MENA has expanded to OTT in other EU regions, some that are direct-to-consumer (e.g., apps and online), and others via telecom/cable carrier partners. Overall their total reach as of Jan. 2021 is 55 regions. | |

| Mnet Movies | ||

|

PAY/SVOD | Africa | |

| Multichoice | ||

|

TVOD | Africa | |

| Showmax | ||

|

SVOD | Africa. In 2021, there will be increasingly African-focused content, and therefore less appetite for internationally-sourced indie material, although there will be some exceptions (e.g., for African-filmed or coproduced content). | |

| IVI | ||

|

SVOD | Russia |

Asia

Niche

| Crunchyroll | ||

|

anime | SVOD, AVOD | Crunchyroll has added AVOD in addition to SVOD, and is now global. |

| Docubay | ||

|

docs | SVOD, Linear | India. As noted above, DocuBay has added linear channel option beyond mere SVOD. |

More Mainstream

| Alibaba / Youku | ||

|

multimodel | China | |

| Viu | ||

|

SVOD/AVOD | Asia |

Canada

Niche

| OUTtv | ||

|

LGBTQ | SVOD | (different from OutTV Netherlands). Canada’s OUTtv, beyond North America, is also in South Africa and New Zealand. It also has begun funding Originals. |

More Mainstream

| Crave | ||

|

SVOD | Canada. Crave has added a French language (Québécois) variation. |

OTHER: Note there are many other international micro-niche sites you can sell to non-exclusively, such as kids, short form episodic/webseries, wildlife, expats/diaspora, lifestyle, gardening, dance, millennials, reality, hobbies, and series, but as they are generally not applicable for most TFC filmmakers, I don’t list them here.

In 2021, more micro-niche thematic sites continue to abound, such as children’s content (Hopster, with multiple competitors around the world), wildlife specialized sites (Love Nature), expats/diaspora (Afroland, ZeeTV), nonfiction reality entertainment (Insight.tv), performing arts (Marquee.tv), and others including gardening, dance, millennials, and other hobbies. Many OTT box offerings are also curating theme channels and microthemed channels, such as Pluto, Roku, etc.

Takeaways

As before, our basic rules have not changed:

- Act quickly and work collaboratively (filmmakers + agents/distributors) to seize timing opportunities.

- Balance traditional and digital to best capture cumulative and incremental revs in the non-exclusive deal sector, while also developing a longer term platform pipeline.

- Be aware many platform buyers rarely attend markets/festivals and instead work virtually (even pre COVID-19, as I did) to better allocate their leaner budgets towards programming spend, rather than markets.

- Don’t stop at just one deal, unless exclusivity or funding elements are in play and worth it.

- Don’t be blocked per se by rights issues. Pragmatic business deals where others are “cut in’’ can help make those melt away.

- Consider hybrid distribution: traditional and digital specialists sharing the job for maximum bang for your buck: “100% of Zero is still Zero”

- After the deal is done – Help audiences know where to find your film!

I look forward to seeing more of your films and docs here and in other parts of the world!

— Wendy Bernfeld, Rights Stuff • @wbernfeld

David Averbach March 1st, 2021

Posted In: Uncategorized

Recent Blog Posts on Distribution

A review of all of our distribution-related articles of the past year or so… enjoy!

New Blockchain Distribution Platform in India

VOD Distribution in India + New Blockchain Distribution Platform/Service

Light of the Moon Case Study

SXSW Case Study Discussion – The Light of the Moon

Making Distribution Choices with Your Film

Making Distribution Choices with Your Film

Intelligent Lives Case Study

Education Market (Outcast)

Evolution of the Education Market

Blockchain Articles

Legal Issues with Blockchain Technology (Part 3 of a 3-part series on Blockchain)

Social Media Articles

Social Media Update for Indie Filmmakers, Part 1: Facebook

Social Media Update for Indie Filmmakers, Part 2: Instagram

Social Media Update for Indie Filmmakers, Part 3: Twitter

David Averbach April 15th, 2019

Posted In: Uncategorized

The Evolution of the Education Market

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

As the summer winds down and the new school year approaches, Outcast Films is revving up marketing initiatives for our fall releases. Rolling around in the back of my head is how much technology has changed the business of film distribution: everything from how we position the films to our audience of teachers and librarians to how we deliver the films.

Our primary goal at Outcast is servicing our customers: teachers and librarians. These are the folks that are going to pay money to purchase and rent your film. I think you will agree with me that if teachers and librarians don’t know about the fantastic new documentary you just finished, then what’s the point?

When I started Outcast Films in 2004, we were distributing VHS tapes. A few years later, DVDs (and Blu-rays) hit the market and VHS tapes were quickly made obsolete. Now, here we are in 2018, with educational digital platforms like Kanopy, AVON (Alexander Street Press), and Hoopla, all of whom service the educational and library markets, not to mention Amazon, Netflix, iTunes and so on, digital is moving at light speed forward.

Two years ago, 95% of our income came from DVD sales. Last year that number dropped to 75% and halfway through this year DVD sales only represent approximately 45% of our total sales. By the end of 2020, I believe DVDs will be just like VHS tapes and dinosaurs. There will be some DVD/Blu-ray sales, of course, but for students, teachers, and the increased demand for on-line college classes in the U.S. digital is the future. The problem is technology should work for everyone—big and small – and it doesn’t.

For this blog, I am focusing solely on the educational market, which is Outcast Films’ area of expertise. But giant tech companies like Amazon, Netflix and Hulu also play a huge factor especially in collapsing the markets. For a couple years now, Netflix has been demanding hold back rights for up to three years from the educational platforms like Kanopy and AVON. Now other big tech companies are placing the same demands on producers: you can come with us or go with Kanopy. Most filmmakers will obviously take the bigger money contracts. (I know I would.) But ultimately, this is driving the cost down for consumers which is good for all of us who like to watch films but bad for the bank accounts of filmmakers.

Kanopy’s collection has comprised of approximately 30,000 titles and AVON has over 100,000. It is impossible for these platforms, to market all their films, all the time. That is not a knock against Kanopy or AVON, I think they have been leaders in the industry and I have a tremendous amount of respect for them. They are providing a great service that students and teachers love.

However, a recent monitoring of VIDLIB, a listserv frequented by academic librarians, reveals that many of them are beginning to rail against some platforms like Kanopy and AVON. You can access the entire discussion by signing up for the VIDLIB listserv but for your convenience, I’ve included some anonymous excerpts below:

- “We are concerned about our rising costs from Kanopy”

- “I believe many of us could not foresee just how expensive streaming, DSLs, etc. would cost us in the long run.”

- “Librarians jobs have become more accountant in nature than collection development.”

- “Trying to balance the needs of faculty/our community for access with a commitment to continue to develop and maintain a lasting collection is difficult.”

- “Our IT department is over-taxed as is and does not have the resources to devote to hosting streaming video files.”

- “We basically had to stop all collection development.”

- “The paradox of increasing production and availability of media resources and shrinking acquisition budgets, due to streaming costs is a disturbing trend, particularly when considering that 100% of our video budget went to DVD acquisitions just four years ago.”

- “(our budget for DVDs) is $20,000 and there’s no way we can purchase in-perpetuity rights for digital files; and, really, there’s no way we can ‘do it all’ or meet all needs.”

- “We love Kanopy – but when it costs $150/year to just provide access, not ownership, to one title, it’s really, really hard to justify.”

- “State legislators are beginning to put pressure on schools to find ways to reduce the cost of things like books, etc.”

- “When colleges and universities are already under fire for the cost of textbooks, etc., asking students to pay one more additional cost gets lumped into the argument about the increasing cost of higher education.”

The concerns these librarians have expressed have been on a slow simmer the last few years but it’s only a matter of time before they hit a full-on pasta boil. One of the most significant concerns, and the one that will affect filmmakers most, is the high cost of streaming.

Another factor that we need to consider is the copyright law and the “Teacher’s Exemption”. With the help of the University of Minnesota, the law is simplified below:

- The Classroom Use Exemption

- Copyright law places a high value on educational uses. The Classroom Use Exemption (17 U.S.C. §110(1)) only applies in very limited situations, but where it does apply, it gives some pretty clear rights.

- To qualify for this exemption, you must: be in a classroom (“or similar place devoted to instruction”). Be there in person, engaged in face-to-face teaching activities. Be at a nonprofit educational institution.

- If (and only if!) you meet these conditions, the exemption gives both instructors and students broad rights to perform or display any works. That means instructors can play movies for their students, at any length (though not from illegitimate copies!)

In other words, if a teacher is going to use the film in their classroom, and they teach in a public university or high school, they do not need anybody’s permission to stream the film to their students.

That’s not the best news for filmmakers but I always say: facts are your friends. Knowing that they won’t need your permission, what can you do to ensure teachers see (and love) your film?

Stay with me because I’m going to ask you to do a little math:

If a librarian has a budget of $20,000 a year for films, at an average cost of $150 for a one-year digital site license (DSL), then they can expect to rent approximately 133 DSLs a year. According to Quora, there are nearly 10,000 films currently being made each year and that number is growing (thanks in large part to technology.) The bottom line is that you have a 1.3% chance that your film will be rented by that university or college. If we increase the library’s budget 5 times, your chance increases to 6.5% which are not great odds.

Facts are our friends. If independent film producers and companies like Outcast Films are going to survive in this volatile business, we need to embrace the facts to solve the problems which means doing your homework. Filmmakers who think they have a great film for the educational market, will have to make their film available through digital platforms. But if they want to increase their odds of selling the film, you will also have to do their own marketing – or hire someone who has experience in the business to help you.

Here are a few tips to help you get started:

- Define and establish your goals as soon as possible

- Write copy for your film with your audience in mind (i.e. teachers are going to want to know how they can use this film in their class)

- Organize a college tour before you turn over the rights of the film

- In the process, find academic advocates who will present the film at conferences AND recommend it to their librarians.

The educational market is a very important audience to reach for many filmmakers. I think most folks reading this blog would agree there is not a better way to educate than by using film. The educational market can also be lucrative, but librarians cannot sustain the increase in costs for steaming over the long haul. As information flows freely through technology, teachers are becoming savvy to the business and realize they don’t need permission to stream a film in their classroom if they respect the criteria set forth in the copyright law.

Remember, facts are our friends. If you think your film is perfect for the educational market, then do your homework: research, strategize and find partners who will help you.

David Averbach August 1st, 2018

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, education, Netflix, Uncategorized

How viable is DIY Digital Distribution? The Case Study of Tab Hunter Confidential

David Averbach is Creative Director and Director of Digital Distribution Initiatives at The Film Collaborative.

When distributing your film, a lot of time is spent waiting for answers. Validation can come only intermittently, and the constant string of “no”s is an anxiety-ridden game of process of elimination. Which doors open for your film and which doors remain closed determines the trajectory of its distribution, whether it’s festival, theatrical, digital, education or home video (until that’s dead for good).

I work with filmmakers, way down-wind of this long and drawn-out process, who, after exhausting all other possibilities, have “chosen” DIY digital distribution as a last resort.

TFC’s DIY digital distribution program has helped almost 50 filmmakers go through the process of releasing their film digitally over the past 5 years and with most of them, I have often felt as though I were giving a pep-talk to the kid who got picked last for the dodgeball team. “Hang in there, just stick to it…you’ll show them all.”

Is DIY Digital Distribution anything more than a last resort? Perhaps not…

DIY vs. DOA

Since TFC was formed over six and a half years ago, we have optimistically used “DIY” as a term of empowerment, where access and transparency had finally reached a point where one could act as one’s own distributor. After all, we tell these (literally) poor, exhausted filmmakers, “no one knows your film better than you do”, so “no one can do a better job of marketing it.” With a little gumption, a few newsletters and handful of paid Facebook posts, you, too, might prove all the haters wrong and net even more earnings than Johnny next door who sold his film to what he thought was a reputable distributor but never saw a dime past the MG (minimum guarantee) in his distribution agreement. We even wrote two case study books about it.

It’s not that I’m being untruthful with these filmmakers. Nor is it the case that these films are necessarily of poor quality. What they have in common is a lack of visibility. Most had some sort of festival run, and only a handful were released theatrically, usually with one- or two-day engagements in a handful of cities. Occasionally, we’ll get a film that has four-walled in New York or Los Angeles for a week. Or sometimes ones that have played on local PBS affiliates or even on Showtime. But their films are not even close to being household brand names. So without the exposure or the marketing budget, they can do little more than to deliver their film to TVOD platforms like iTunes and hope for the best.

So what happens to these films? The news, as a whole, is not good. Based on what I’ve seen from these films in the aggregate, and all things being equal, if you DIY/dump your film onto only iTunes/Amazon/GooglePlay with moderate festival distribution but no real money left for marketing, you will be lucky to net more than $10K on TVOD platforms in your film’s digital life.

And the poorer the filmmaking quality of your film, or the less recognizable the cast, or the less “niche” your film is, the more likely it will be that you won’t even earn much more revenue than what is required to pay off the encoding and delivery fees to get your film onto these platforms in the first place (which is around $2-3K).

Which is why, as of late, I’ve been aggressively suggesting to filmmakers that holding off on high profile TVOD platforms and instead trying to drive traffic to their websites and offering sales and rentals of their film via Vimeo On Demand or VHX, two much cheaper options, might be a better use of their limited remaining funds.

But am I down on DIY? Not necessarily.

Risky Business

Granted, there are a lot of films out there for which The Film Collaborative can do very little for in the area of digital distribution other than hold filmmakers’ hands. But what about for films working at the “next level up” from last-resort-DIY? Films who have either gotten a no-MG or modest-MG distribution offer?

Many distributors and aggregators working at this level will informally promise some sort of marketing, but many times those marketing efforts are not specifically listed contractually in the agreement. So when filmmakers ask me whether going with a no-MG aggregator is better than doing DIY, this is my answer…

It’s important to remember that, once a film is on iTunes, no one will care how it got there. And by this I mean with no featured placement, just getting it on to the platform. So, if that’s all a distributor/aggregator is doing, this is not the kind of deal that a filmmaker can dump into someone else’s hands and move on to their next project. In fact, many aggregators will send you a welcome packet with tips and suggestions on how to market your film on social media, such as Facebook. In other words, they are literally expecting you to do your own marketing. Not just do but pay for. So, it is entirely possible that all that an aggregator or distributor is doing is fronting your encoding costs, which they will later recoup from your gross earnings, but only after they take their cut off the top. And if your distributor is offering you a modest MG, you must be prepared for the possibility that that MG may be all the earnings you are ever going to see. Certainly, we have seen many, many filmmakers in this position.

So the question remains: Is DIY still too risky for all but films that have run out of options?

It’s a hard question to answer, mostly because there is no ONE answer. Undoubtedly, some films will be helped with such an arrangement and some films will not.

A View from the Other Side…

Distributors, of course, will stick to the sunny side of the street. They will tell you that DIY is too risky for the vast majority of films, and remind you that distribution is more than getting a film on to one or two platforms.

When I asked Gravitas Ventures founder Nolan Gallagher, a veteran in distribution and whose co-execs have a combined 50+ years in distribution experience, about his feelings regarding DIY, he was quick to point out that the main difference between a proven distributor and DIY is that while much of the work in DIY happens in year 1, distributors can help in year 3 or year 5 or beyond. He believes that DIY individual filmmakers will be shut out from new revenue opportunities (i.e. the VOD platforms of the future) that will be launched by major media companies or venture capital backed entrepreneurs in the years to come because these platforms will turn to established companies with hundreds or thousands of titles on offer.

This is a fair point, in theory, but I honestly cannot recall a single instance of one of our filmmakers from 2010-2013 jumping for joy over that fact that his or her distributor had suddenly found a meaningful new VOD opportunity in years 3-5, nor have we heard of any specific efforts or successes down the line. But it’s good to know one can expect this if signing with a distributor.

He also mentioned that many of Gravitas’ documentarians receive multiple 5 figures in annual revenue over 5 years after a film first debuted.

That’s nice for those filmmakers…But what about the ones that don’t? It would be ludicrous to suggest that any decent film, with the proper marketing and industry connections, can become a respectable grosser on iTunes.

By no means am I singling out Gravitas in order to pick on them in any way. For many films, clearly they do a terrific job.

But does that mean that there aren’t a handful of filmmakers that have gone through aggregators like Gravitas or other smaller distributors that many TFC films have worked with, such as The Orchard, A24, Oscilloscope, Virgil, Wolfe, Freestyle Digital Media, Breaking Glass Pictures, Amplify, Wolfe, Zeitgeist Films, Dark Sky Films, Tribeca Films, Sundance Selects, who are not entirely convinced that they were well served by their distributor? Of course not.

The Million Dollar Question…

The question I really wanted to know was more of a hypothetical one than one that assigns blame: if these so-called “borderline films” that went through aggregators/distributors had done DIY instead, how close could they have come netting the same amount of earnings in the end? Is it possible that they could have gotten more?

This is a hard question—or, should I say, a nearly impossible question—to answer, because no one has a crystal ball. But also because of the continued lack of transparency surrounding digital earnings, despite initiatives like Sundance Institute’s The Transparency Project, and because the landscape is continually evolving.

A recent article in Filmmaker Magazine, entitled “The Digital Lowdown,” discusses how independent filmmakers struggle to survive in an overcrowded digital marketplace and “admits” that niche-less festival films will only gross in the range of $100K-$200K, and that, in fact, talks about a “six-figure goal.” But in almost the same breath, there is a caveat. Sundance Artist Services warns that “…if a filmmaker spends about $100,000 in P&A to finance a theatrical run, they’re probably going to be making that much from digital sources.”

I have heard many stories of distributors and filmmakers alike, who put “X” dollars combined into P&A for both theatrical and digital only to make a similar amount back in the end. So what’s the point? If you look at distribution from the perspective of paying back investors, are a good portion of filmmakers netting close to nothing, no matter whether they do DIY or whether they gear up for a theatrical and digital distribution via a distributor? If a film does not succeed monetarily, is the consolation prize merely visibility and exposure? (Which is not nothing, but it’s not $$ either).

Sweet/Talk

A few months ago, my colleague Bryan Glick posted a terrific piece on our blog that questioned the ROI of an Oscar®-qualifying run, given the unlikelihood of being shortlisted. Bryan implies that because filmmakers like hearing “yes,” and like having their egos stroked, when publicists, publications, screening series, cinemas, and private venues all lure filmmakers with a possibility of an Oscar®, something takes over and they lose perspective at the very moment they need it most.

Could the same be true for a distribution strategy? Are filmmakers so happy to be offered a distribution deal at all that they are unable to walk away from that distribution deal, even if they suspect that it undervalues their film? And could a viable DIY option change that?

Evaluating Success with DIY

Last fall, I began to think about what a “successful” DIY digital release could look like. On the low end, we’ve heard about a magical $10K figure that I discussed above…in the context of MGs paid to Toronto official selections via Vimeo on Demand, and Netflix offers to Sundance films via Sundance Artists Services. So it would have to be at least greater than $10K. And on the high end, it would have to be at least $100K that the filmmaker gets to net over a 10-year period.

Working backwards, how can this be achieved and is it possible to recreate that strategy via DIY?

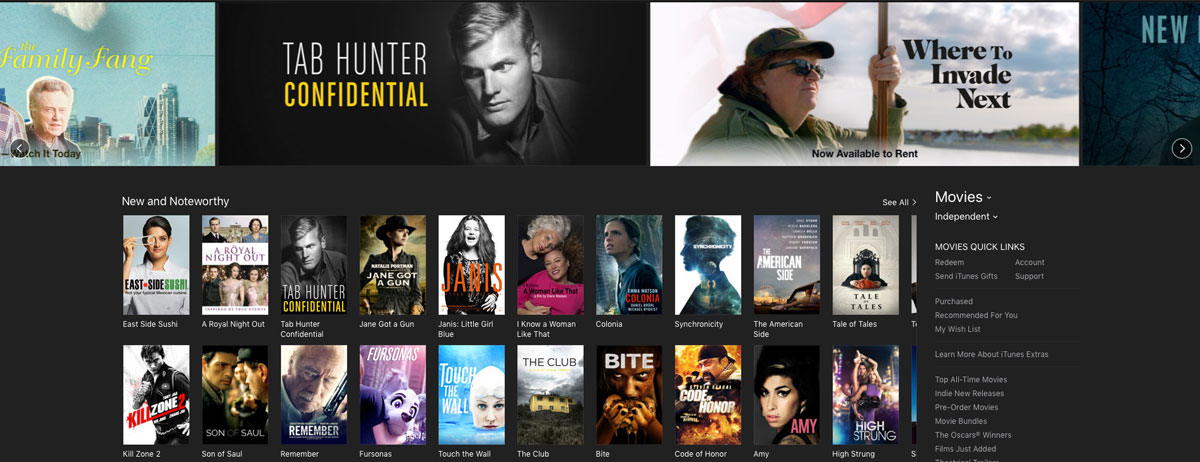

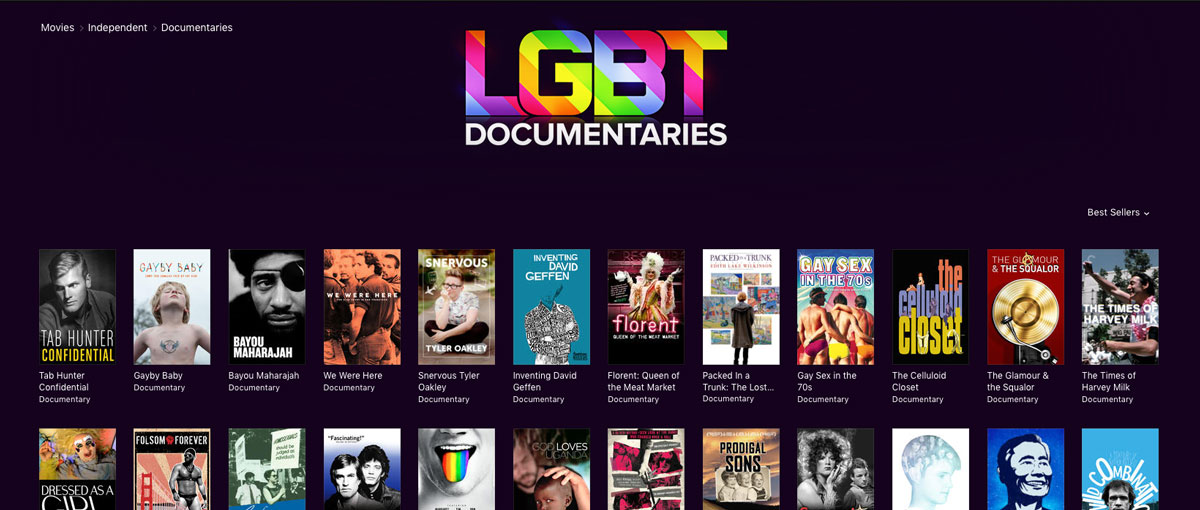

One thing that gave me hope was when my colleague Orly Ravid, acting as sales agent, negotiated a licensing low-six-figure deal with Netflix for the film Game Face, about LGBTQ athletes coming out. The film won numerous audience awards at film festivals, but had no theatrical release. Timing, as well as the sports and LGBT niche, made this film perfect for a DIY release. The only catch was the Netflix insisted on a simultaneous SVOD & TVOD window, so Netflix and iTunes releases started within one day of each other. TFC serviced the deal through our flat-fee program via Premiere Digital Services.

Lessons Learned from the DIY Release of Tab Hunter Confidential