Don’t Just “Take the Plunge” in a Distribution Deal

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To • by Orly Ravid

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next • by David Averbach

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals • by Orly Ravid and David Averbach — COMING SOON

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To

by Orly Ravid

We know from filmmakers the reasons they often choose all rights distribution deals, even when there is no money up front and no significant distribution or marketing commitment made by the distributor. Regardless of whether the offer includes money up front, or a material distribution/marketing commitment, we think filmmakers should consider the following issues before granting their rights.

The list below is not anything we have not said before, and it’s not exhaustive. It’s also not legal advice (we are not a law firm and do not give legal advice). It is another reminder of what to be mindful of because independent film distribution is in a state of crisis, and we are seeing a lot of filmmakers be harmed by traditional distributors.

Questions to ask, research to do, and pitfalls to avoid

- Is this deal worth doing?: Before spending time, money, and energy on the contract presented to you by the distributor, ask other filmmakers who have recently worked with the distributor if they had a good (or at least a decent) experience. Did the distributor do what it said it would do? Did it timely account to the filmmakers? These threshold questions are key because once a deal is done, rights will have been conveyed. So ask that filmmaker (and also decide for yourself) whether they would have been better served by either just working with an aggregator or doing DIY, rather than having conveyed the rights only to be totally screwed over later.

- Get a Guaranteed Release By Date (not exact date but a “no later than” commitment): If you do not get a “no later than” release commitment, your film may or may not be timely released and, if not, the point of the deal would be undermined.

- Get express specific distribution & marketing commitments and limitations / controls on recoupable expenses: To the extent filmmakers are making the choice to license rights because of certain distribution promises or assumptions about what will happen, all of that should be part of the contract. If expenses are not delineated and/or capped, they could balloon and that will impact any revenues that might otherwise flow to the filmmakers. There is a lot more to say about this including marketing fees (not actual costs, but just fees) and also middlemen and distribution fees. But since we are really not trying to give legal advice, this is more to raise the issues so that filmmakers have an idea of what to think about.

- Getting Rights back if distributor breaches, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy: Again, lots to say about this which we will avoid here, but raising the issue that if one does not have the ability to get their rights back (and their materials back) in case a distributor materially breaches the contract, does not cure it, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy, then filmmakers will be left having their rights tied up without any recourse or access to their due revenues. It’s a horrible situation to be in and is avoidable with the right legal review of the agreement. Of course, technically having rights back and having the delivery materials back does not cancel already done broadcasting, SVOD, AVOD and/or other licensing agreements, nor can one just direct to themselves the revenues from platforms or any licensees of the sales agent or distributor (short of an agreement to that end by the parties and the sub-licensees)…but we will cover what is and is not possible in terms of films on VOD platforms in the next installment of this blog.

- Can you sue in case of material breach? Another issue is, when there is material breach, does the contract allow for a lawsuit to get rights back and/or sums due? Often sales agents and distributors have an arbitration clause which means that the filmmakers have to spend money not only on their lawyer(s) but also on the arbitrator. Again, there is much more to say about this, but we just wanted to raise the issue here. There are legal solutions for this, but distributors also push back on them, which gets us back to the first point, is this deal worth doing? Because if the distributor’s reputation is not great or even just good, and, on top of that, if it will not accommodate reasonable comments (changes) to the distribution deal that would contractually commit the distributor to some basic promises and therefore make the deal worth doing and protect the filmmaker from uncured material breach by the distributor, then why would you do that deal?

Filmmakers too often just sign distribution agreements without understanding what they are signing or without hiring a lawyer who knows distribution well enough to review the agreement. This is foolish because once the contract is signed and the delivery is done, the film is out of the filmmakers’ hands and they will have to live with the deal they made. If that deal was not carefully vetted and negotiated, then the odds are that it will not be good for the filmmaker. Filmmakers can make their own decisions, but we urge them to be informed.

How to best be informed:

- Get a lawyer who knows distribution

- Check out our Case Studies

- Read the Distributor ReportCard to see what other filmmakers have said about a distributor and/or find filmmakers to talk to on your own who have used them recently. If we haven’t covered a certain distributor in the DRC but one of our films has used them, just contact us. We could be happy to ask them if they’d be willing to speak with you, and, if so, make an introduction.

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next

By David Averbach

When TFC started our digital aggregation program[1] in 2012, there was a palpable sense of possibility, that things were changing–access was opening up, and filmmakers were finally being given a more even playing field. Who needed middlemen when one could go direct [2]!?

In many ways, going direct, choosing to self-distribute, was (and maybe still is) viewed a bit like electing to be single, as opposed to the “security” of a relationship and/or a marriage. When your film gets distribution, it’s a little bit like, “They said, ‘yes!’ Somebody loves me. I don’t have to go it alone.” Less stigma, more legitimacy.

Relationships and distribution deals have a lot in common. If you are breaking up with your distributor, it can get messy. That’s why TFC Founder Orly Ravid has outlined above some of the basic concepts and things you can do with your lawyer to make sure that if you choose to do a deal, you protect yourself as you enter into a binding relationship. Like a pre-nup. So that you get to keep everything you brought with you into said relationship when you part ways.

Good News, Bad News

So, let’s say there is good news in the sense that you are able to hang on to whatever belongings you brought into the relationship.

But there’s bad news, too. Your ex is keeping all the stuff you bought together.

At least it’s going to feel like that. I know…you would rather kick your ex out and stay in your apartment. Really, I get it. But it’s not going to happen. It’s going to feel like your ex has all your stuff and won’t give it back. Because you are not going to feel grateful like Ariana; you will want someone to blame. But that’s not really fair. Because it’s more like you are both getting kicked out of the apartment and technically your partner still owns all the stuff that’s still inside, but also that they changed the locks and neither one of you can get back inside and access it. And, also, you are now homeless. Good times.

OK, let’s back up for anyone confused by the breakup metaphor: You got the rights to your film back.[3] Yay! Your film is up on all these platforms. All you want to do is keep it up on those platforms. Sorry, not gonna happen. You’re going to have to start again from scratch.

Why you have to start from scratch with most platforms when you get your rights back.

I know, you have questions. From a common-sense perspective, it makes zero sense. I’m going to go through the reasons as to why this is the case, on a sort of granular, platform-focused basis, but the answers I think say a lot about how the distribution industry is and, in many ways, has always been set up. And it underscores everything I’ve always suspected about the sorry state of independent film distribution.

I have to thank Tristan Gregson, an associate producer and an aggregation expert of many years, who was generous enough with his time to rerun questions that filmmakers have asked him over the years about salvaging an existing distribution strategy, and why, unfortunately, it is pretty much impossible.

So, let’s begin by limiting our parameters. I mentioned shared materials that were created after your deal was signed. If your distributor created trailers and artwork, I suppose that technically they own the rights, even though your distributor probably recouped their cost, but the train has left the station on those, so how likely is it that someone would go after you for continuing to use them? I would recommend making sure you have a copy of the ProRes file for your trailer and layered Photoshop files (along with fonts and linked files) or InDesign packages for your posters before things go south, because you are going to need the originals again when you start over. I’m assuming you still possess the master to your actual feature. And don’t forget about your closed captioning files.

Licensing deals (that ones that come with licensing fees) have been harder to come by for many years, but if your distributor has licensed your film to a platform, the license itself would be unaffected, so that would not have to be “recreated,” so to speak.

The rest—the usual suspects: transactional platforms (TVOD), rev-share based subscription platforms (SVOD), and ad-supported platforms (AVOD) (in other words, situations where revenue is earned only when the film is watched)—are what I’m going to be focusing on here.

Let’s say your film is up on a handful of TVOD and/or AVOD platforms. Why is it not possible for them to remain up on those platforms?

In the best of all possible worlds, couldn’t somebody simply flip a switch, change some codes, and point all the pages where your film currently lives to a new legal entity and let you continue on your merry distribution way?

But who exactly is this “someone”? They would have to have a direct contact at the platform. So maybe that’s your distributor, maybe it’s their aggregator. And is this contact at the platform the person who will do this? Probably not. It’s probably someone who deals with the tech. So now, you need to mobilize a small army of hypothetical people who are all willing to do this work for you for free. For each platform that you’re on. And don’t forget things between you and your distributor are complicated and tense right now. They are going to do you a favor to save you a few thousand bucks?

But it’s actually worse than that. You would also be assuming that Platform X, who perhaps is also trying to sell books, goods, phones and tablets, actually cares one single iota about your tiny (but fantastic) little film enough to do this for you. They do not. Despite happily taking 30-50% of your selling price for all these years. They absolutely do not.

The Nitty Gritty

I had suspected this, but I sought out Tristan for confirmation. I had only spoken previously to Tristan on a handful occasions, but he is an affable guy. Gregarious but not to the point of being garrulous. He cares. Talking to him, you get the feeling that he would go the extra mile for you if he could. Please remember this as he recites answers that he has probably given more times than he can count. His cynicism is well earned…it comes from experience.

[Note: I’ll ask and answer some of my own questions in places. Tristan’s responses will be in italics, mine will be in plain font.]

You are my distributor’s aggregator. Can’t I just work with you directly?

The answer is yes, if you start from scratch. But your distributor paid for the initial services. They paid to have it placed there. Not you.

But I made the film, and I got my rights back. Why can’t you tell Platform X to keep it up there and just change where the money should go?

Yes. I know your name is listed. But that string of 1s and 0s is associated with your distributor, not you.

It all comes back to tech. Because at the end of the day, it’s a string of 1’s and 0’s that are associated with a media file. It’s not your movie in a storefront or on a digital shelf or anything like that. In the encoding facility/aggregator world, these 1’s and 0’s are the safety net for us. We have an agreement with Party X. If Party X ends the relationship or ceases to exist, it’s written into that agreement that we pull everything down—we kill it from our archives. We’re protecting everyone. We don’t want to hold onto assets that we don’t have any relationship with. Those strings of 1’s and 0’s that go up onto a platform, and that platform has an ID tag that’s tied with the back end of the system, and that system reconciles the accounting, and the accounting reconciles with the payout. We can’t go in and just change a name on a list. That’s just not how that works.

You (the independent filmmaker with a movie) do not have a relationship, direct or indirect, with any of the platforms your distributor placed your title onto. As such, your title would not continue to be hosted at any of these outlets should your relationship with your distributor officially end. People often would say “it’s my movie, now that Distributor X is gone, just have the checks go to me.” That’s not how the platform or the aggregator ever see it, which I know is very painful for the creator who may now think they control “all their rights.”

It’s just a business entity change.

Aren’t you going to be sending me a new file anyway? Isn’t the producer card or logo going to change at the beginning the film? That’s gotta be QC’d again, in any event.

Are you telling me that if I had a 100-film catalogue, I’d have to re-QC 100 titles from scratch? That’s insane.

Let’s say Beta Max Unlimited Films had 100 titles with us and then, Robinhood Films, who is also a client of ours comes along and says, ‘Hey, we bought Beta Max Unlimited Film’s catalog, we bought all the rights to all of it. Work with us to move it over. All you guys have to do is do it on the accounting end.’ Let’s say we would be willing to do it. And let’s say we contact Platform X, we were to talk to them, talk to our rep there, and they say they are willing to relink all that media on their end, they’ll move the 1’s and 0’s over. Even then, 99 times out of 100, it never happens because you’ve got a bunch of people, and these people are kind of working pro bono on something that doesn’t really matter to them.

Just because you may think something is easy or “no work at all” doesn’t make it true, and even when it is, nobody wants to work for free. Something may be technically possible, but having all the different parties communicate and execute just never happens when nobody’s directly being paid to do the actual work.

Are you kidding me? Platform X wouldn’t move a mountain for a hundred titles?

Like, that’s nothing to them, it means nothing. What matters to them—is that stuff plays seamlessly, and it has been QC’d and approved and published. They don’t need to deviate from this because at the end of the day, it’s not going to help sell tablets and phones.

And again, we’re talking about multiple platforms. What happens if they could do this… and they get 6 out of 8 platforms to comply but the other two are intransigent? They’re going to come back to you and say, “Sorry, we tried. We hounded them 16 times, but these two won’t do it. And now you have to pay anyway to redeliver if you want to be on these two platforms.” You are going to think the aggregator is scamming you. It will not be a good look for them. Why would they want to agree to work for free with the likelihood that they will end up looking bad in the end? KISS (Keep it simple, stupid). It only makes sense to ask you to start from scratch.

Are there platforms I can actually go direct with?

You can do Vimeo On Demand on your own. (Note that for top earners [top 1%], there may be an extra bandwidth charge. You can read more about that here).

You can also do Amazon’s Prime Video Direct.

Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick…More on these later.

I thought Amazon wasn’t taking documentaries?

I believe that’s still true? However, I have access to a small distributor’s Amazon Video Direct portal. In 2021, there was a big, visible callout that said something to the effect of, “Prime Video Direct doesn’t accept unsolicited licensing submissions for content with the ‘Included with Prime’ (SVOD) offer type. Prime Video Direct will continue to help rights holders offer fictional titles for rent/buy (TVOD) through Prime Video. At this time Amazon Prime does not accept short films or documentaries.” This is June 2023. I cannot find this language anywhere in the portal. But I believe that is still the case.

What about “Amazon Prime” SVOD?

In the portal, all the territories that were once available for SVOD are still “listed,” it’s just that the SVOD column whereby you could check each one off is gone. So, no SVOD for unsolicited fiction. If you create your own Amazon Video Direct account, the territories that are available in an aggregator’s account might differ from an individual filmmaker’s account. All this seems to be moot if SVOD is not available.

So, for Amazon, it’s only TVOD?

Yes.

[Sidebar: It has usually just been US, UK, Germany, and Japan. Amazon just announced Mexico, but for this option to be available in your portal, one needs to click a unique token link that was sent out. The account I have access to received this notification. I am not certain whether this link was or will be sent out to all users. Localization is required for the non-English speaking territories in this category.]

But my distributor had gotten my documentary onto Amazon. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to once again allow it in?

Best of luck with that. Amazon is notoriously difficult and unresponsive, even with aggregators. You can try, and even if it is initially rejected, there is an appeal link somewhere in the portal that you can write in to. I have no idea if that will do any good.

My film was Amazon Prime SVOD. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to keep it in there?

“Keeping it” is not the most accurate way of looking at the situation. It’s basically going to create a new page. And that will be controlled by the back-end in your personal account. SVOD will probably not be an option in this account. You can write in, as mentioned above, but it seems as though Amazon is trying to lessen the content glut for its Prime Video service, so I have my doubts as to whether very many people who make this request prevail.

Wait…what??! You mean that I will have a new page and therefore will lose all my reviews?

Yes and no. The old page and reviews might still be there, but “currently unavailable” to rent or buy. But on your page, the page where it is available, the reviews will not carry over. Reviews not carrying over is probably true for all platforms, but Amazon reviews are more prominent than on other platforms, so they are usually what filmmakers care about the most.

My distributor had gotten my film onto AVOD platforms Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. Do I have a better chance of getting my “pitch” accepted because it was on there before?

No.

But why? It was making some pretty good money.

You are assuming that the Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. acquisitions person is the same person who approved your film in the first place, and even then, they are going to remember your film, or are going to take the time to look up your film and see how it was doing, and also that amount of earnings you may have gotten is going to mean enough to them to matter.

If I somehow could convince someone to keep assets in place, there’s no downside, right?

Actually, that may not be true. It’s about media files meeting technical requirements, which change over time. What was acceptable yesterday isn’t always acceptable today. So when you attempt to change anything at the platform level, you risk removal of those assets already hosted on a platform.

OK, I think you get the point.

Tristan reminded me that you need to think of yourself as a cog in the tech machine.

You think all this is too cynical? Think about it…

It’s always been that way, even though we never wanted to believe it. Take the Amazon Film Festival Stars program circa 2016 as an example. A guaranteed MG. Sounded great. But on a consumer-facing level, did they make any attempt to create a section on their site/platform where discovery of these purported gems could take place? No. Did you ever stop to ask yourself why? Because at the end of the day, they didn’t really care. Any extra money they would have made was so insignificant to them that it was not worth the effort. So, they discontinued the program and blamed lack of interest.

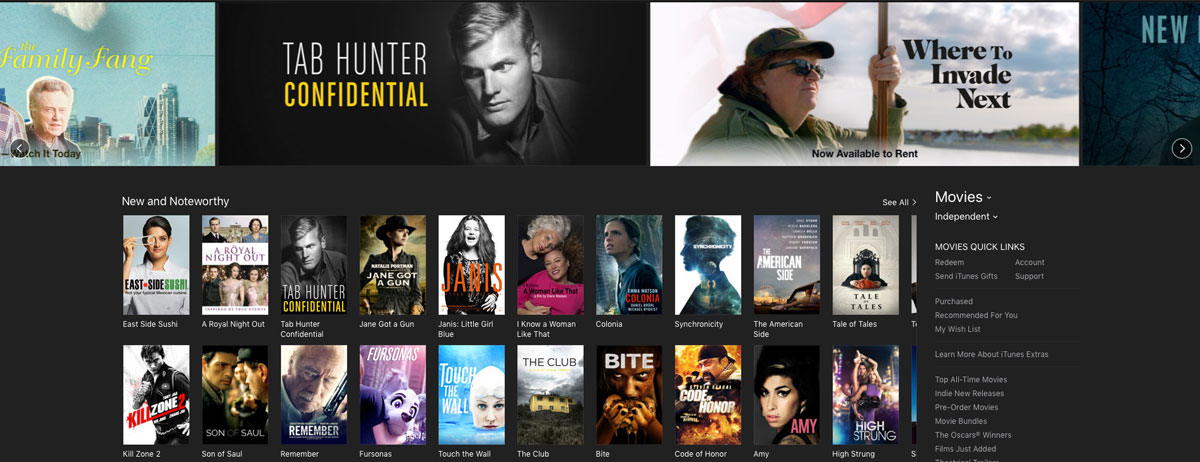

To be fair, iTunes for many years had a very selective area for the independent genre. But it’s gone/hidden/trash now with AppleTV+. They would rather peddle their own wares than create a section that champions festival films. And remember that one, poor guy who I shall not name that you had to write to and beg in order to get your film even considered for any given Tuesday’s release? Even if you were lucky enough to be selected, if your film didn’t perform well enough it would be gone from that section by Friday morning. Or by Tuesday of the following week. All that seems to be gone now. Independent films don’t make money for them. Even though they are willing to spend $25M on CODA and $15M on Cha Cha Real Smooth.

And every so often, new platforms (like Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick) emerge that want to change this. There are films that you actually recognize, that have played in festivals alongside yours…just…listed all together! But, have you heard of these platforms, let alone rented a film off one of them platforms or paid a monthly subscription fee? Chances are you haven’t.

This is not to blame you. But by all means, check these mom-and-pop platforms out and support your fellow filmmakers. And these are not the type of platforms that would be so hard to re-deliver to anyway. They’d probably be happy to go direct with you. It’s the big platforms that are calling cards, the ones that everyone uses, that you will want to be on even if you secretly know they are not bringing in much in terms of revenue. But either way, these platforms don’t care.

Let’s remember why aggregators exist. It’s because platforms don’t care, couldn’t be bothered, and waived their magic wand over some labs out there and said, “Now you deal with them. You be the gatekeepers.” And a whole business sector was created.

There are some distributors out there who have been around for a while that may very well have contacts at some of these platforms, but it doesn’t matter. You don’t have those connections, and chances are that they are drying up for these distributors, too.

And while this is crushing, it might also be freeing.

Tristan echoed what TFC has been saying for years: You are your own app, your own thing, most importantly, your own social media marketing campaign.

If you think about getting into bed with a distributor being like a relationship or a marriage, then your film is the kid you are raising. What kind of parent is your distributor? What kind of parent are you? Your distributor might say they will do marketing (change the dirty diapers), and then do it once or twice, but then they don’t do it again. Who is going to change those diapers it if it’s not you?

So, this relationship metaphor I am positing should not solely be directed at filmmakers who are getting their rights back. When you enter into a deal with a distributor, some filmmakers think they can now be deadbeat parents, when in reality you should co-parenting. And when your relationship with your distributor ends, you still need to raise the kid, right? It’s all on you now. And the truth is, it always was.

Notes:

[1] TFC discontinued our flat-fee digital distribution/aggregation program in 2017. [RETURN TO TOP]

[2] When we say “direct,” we mean direct to a platform, or semi-direct through an aggregator that doesn’t have a real financial stake in your distribution, as opposed to a distributor that takes rights and is (or purports to be) a true partner in your film’s distribution strategy. [RETURN TO TOP]

[3] It’s important to ensure that you have your rights back. Easiest and best way is to ask your lawyer and go through it with them both in terms of your distribution agreement, but also on a platform by platform basis. Also, to the extent that you will need to start from scratch, make sure your distributor’s assets on each platform have been removed or disabled before you attempt to redeliver them to each platform. [RETURN TO TOP]

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals

By Orly Ravid and David Averbach

Coming soon

admin June 8th, 2023

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distributor ReportCard, DIY, education, Legal

Educational Distributor Check-in: Video Project

We’re going to be checking in with a few educational distributors with a brief Q&A over the next few months. The Video Project is the first…stay tuned!

website: VIDEO PROJECT, INC.

What is the range of educational distribution you do, including the various categories of licensees/viewers, and any age/demographics specifics (please address K-12, any government, institutional, etc)?

Video Project is a nonprofit organization that specializes in non-theatrical distribution, including educational licensing and community screenings. We license films to all types of educational institutions, including Colleges, Universities, Community Colleges, and private and public K-12 schools. We also license to public school districts and state Departments of Education. Our institutional reach includes non-profits, libraries, corporations, community groups, government organizations, municipalities, and museums.

Community Screening requests continue to grow and we promote and support them with our website intake form, sales follow up, community screening kits, tech support and fulfillment. We allow filmmakers to work with organizations directly on speaking engagements and book screenings directly if they chose.

What type of distribution arrangements do you do? (e.g. licensing [and what types], screenings, other?)

Video Project is proud to offer flexibility to meet the varied needs of independent producers and their films, but typically we license North American educational and institutional rights, plus non-exclusive worldwide rights. This includes rights for our direct DVD and digital site license educational and institutional sales, as well as sub-distributors, which include Kanopy. Many of our contracts contain non-exclusive community screening rights, which allow for filmmakers to do community screenings directly, and also allows us to fulfill community screening orders. We can also arrange for VOD placement (either exclusive or non-exclusive) and in-flight through a third party. We occasionally also partner with theatrical distributors for limited theatrical screenings.

What is the range (low-middle-high) of both (a) revenue to filmmakers and (b) impact/degree film will have been seen (both in terms of number of venues/outlets/institutions and actual people).

In our experience, revenue and impact is a function of the goals for the film. Every film has its own unique distribution strategy, which we develop and implement together with filmmakers. Revenue is dependent upon many variables, including timeliness and quality of the film, awareness of the film from theatrical and/or impact campaigns, and the availability of the film on consumer streaming platforms or some other free access. While making a film available for free a low-cost streaming can promote broader viewership, it’s much harder for us to sell a license once it is available on low or no-cost platforms.

Impact distribution can serve a critical role in raising awareness of issues, which can lead to engagement and affect change. While measuring impact can be challenging, we have had good success with a number of films to catalyze change, which have been substantiated by evaluation metrics after release.

Sometimes a film is requested by a faculty member for classroom screenings, or by a campus organization for a pubic screening(s). It may be purchased for a media library collection, in which case the film could have impacts on the consciousness of students for decades. We can get approximate audience numbers on community screenings requested through our site, and also in the gifted film campaigns which are mostly targeted to K-12. And films like STRAWS have been used to support single use plastic bans in towns throughout the U.S.

Please describe any impact work you do. What forms does it take? What type of arrangements are involved on both licensor to you side and licensee from you side?

Impact work is a growing part of our business. One of the reasons we decided to become a nonprofit was to facilitate distribution opportunities that lead to engagement and change through filmmaking. Much of our impact work comes in the form of “gifted campaigns,” wherein a donor subsidizes the free distribution of the film, usually to K-12, but also to colleges and universities, as well as other types of institutions. We have also produced live event campaigns for K-12 schools that reached thousands of students. We can also work in parallel with a filmmaker’s existing impact campaign to help create further educational sales. Examples and case studies can be found in our website “impact” tab.

What types of films are most likely to succeed? Which types of films usually do not work?

Some of our most successful films are those that speak to acute or trending issues such as educational justice or plastic straws, and help stakeholders such as nonprofits, government agencies, teachers, administrators, and ultimately students, address those issues. There is also growing interest in films that highlight the history of racism and segregation in schools, films directed by BIPOC about issues in their communities, and films that address current mental health concerns in student populations.

Normally we prefer to maintain educational exclusivity by postponing consumer streaming. A successful educational distribution strategy allows for 1-2 semesters (or sometimes more) of educational sales before it is released onto AVOD and TVOD consumer streaming platforms. TV broadcast is a good way for a film to gain visibility, which can help educational sales, as long as the streaming periods by the broadcast channels are limited.

Films that are most likely to be more difficult to sell are on topics for which the market is saturated, for example, climate change. Films which are widely available on consumer streaming platforms, and have already had extensive visibility may also be difficult to distribute.

Summarize your basic deal terms (term of license, rights, fees, expenses recouped).

Every agreement is different, but our basic deals often include the following:

5 years

Rights:

Exclusive North American Educational and Institutional (U.S. and Canada)

Non-Exclusive Worldwide Educational and Institutional

Rights include direct DVD and Digital site license sales, third party educational streaming, and public library and other sub-distributors.

Non-Exclusive Community Screenings

Expenses:

The only expenses ever charged against filmmaker royalties are for DVD cover graphics, closed captions, and DVD authoring. Maximum total expenses capped at $1,400, and can be reduced if producers can provide said assets.

Fees

None

How you manage issues around commercial streaming and educational streaming conflicts?

If a producer has a streaming deal in the works, we will provide a contractual holdback, stating that we will not release the film to any educational streaming partners without written permission from the producer. We strongly advocate for thoughtful distribution sequencing, to maximize the potential of educational distribution before consumer streaming becomes available.

Any thoughts about the state of educational distribution these days and thoughts about the future?

For the types of films we distribute, including those focused on social justice and the environment, educational sales are still an important way for most filmmakers to monetize their films.

We are told that educational streaming budgets continue to remain strong and could even grow in the future. DVD’s are still being bought by collection-minded school librarians, and by public libraries. Once a film gains a foothold in a teacher’s curriculum, it can be used year after year. And older films still sell; there is a long tail in educational distribution. Impact campaigns can also really help raise the visibility for a film, and we are seeing a growing demand for community screenings, both live and virtual.

Any final comments about Video Project, any tips to filmmakers, and anything else you want to say?

Video Project was formed in 1983. In 2019 we became a nonprofit so that we could better serve our filmmakers. We are very receptive to active collaboration and pride ourselves on being easy to reach and communicative with our filmmakers. If you think your film is a good fit, please do submit your film here.

Orly Ravid December 31st, 2022

Posted In: Distribution, education

The Evolution of the Education Market

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

Our guest blog author this month is Vanessa Domico, who has more than 30 years of business experience in both the corporate and non-profit sectors. In 2000, Vanessa joined the team of WMM (Women Make Movies), first as the Marketing and Distribution Director, and eventually Deputy Director. Wanting to work more closely with filmmakers, Vanessa left WMM in 2004 to start Outcast Films.

As the summer winds down and the new school year approaches, Outcast Films is revving up marketing initiatives for our fall releases. Rolling around in the back of my head is how much technology has changed the business of film distribution: everything from how we position the films to our audience of teachers and librarians to how we deliver the films.

Our primary goal at Outcast is servicing our customers: teachers and librarians. These are the folks that are going to pay money to purchase and rent your film. I think you will agree with me that if teachers and librarians don’t know about the fantastic new documentary you just finished, then what’s the point?

When I started Outcast Films in 2004, we were distributing VHS tapes. A few years later, DVDs (and Blu-rays) hit the market and VHS tapes were quickly made obsolete. Now, here we are in 2018, with educational digital platforms like Kanopy, AVON (Alexander Street Press), and Hoopla, all of whom service the educational and library markets, not to mention Amazon, Netflix, iTunes and so on, digital is moving at light speed forward.

Two years ago, 95% of our income came from DVD sales. Last year that number dropped to 75% and halfway through this year DVD sales only represent approximately 45% of our total sales. By the end of 2020, I believe DVDs will be just like VHS tapes and dinosaurs. There will be some DVD/Blu-ray sales, of course, but for students, teachers, and the increased demand for on-line college classes in the U.S. digital is the future. The problem is technology should work for everyone—big and small – and it doesn’t.

For this blog, I am focusing solely on the educational market, which is Outcast Films’ area of expertise. But giant tech companies like Amazon, Netflix and Hulu also play a huge factor especially in collapsing the markets. For a couple years now, Netflix has been demanding hold back rights for up to three years from the educational platforms like Kanopy and AVON. Now other big tech companies are placing the same demands on producers: you can come with us or go with Kanopy. Most filmmakers will obviously take the bigger money contracts. (I know I would.) But ultimately, this is driving the cost down for consumers which is good for all of us who like to watch films but bad for the bank accounts of filmmakers.

Kanopy’s collection has comprised of approximately 30,000 titles and AVON has over 100,000. It is impossible for these platforms, to market all their films, all the time. That is not a knock against Kanopy or AVON, I think they have been leaders in the industry and I have a tremendous amount of respect for them. They are providing a great service that students and teachers love.

However, a recent monitoring of VIDLIB, a listserv frequented by academic librarians, reveals that many of them are beginning to rail against some platforms like Kanopy and AVON. You can access the entire discussion by signing up for the VIDLIB listserv but for your convenience, I’ve included some anonymous excerpts below:

- “We are concerned about our rising costs from Kanopy”

- “I believe many of us could not foresee just how expensive streaming, DSLs, etc. would cost us in the long run.”

- “Librarians jobs have become more accountant in nature than collection development.”

- “Trying to balance the needs of faculty/our community for access with a commitment to continue to develop and maintain a lasting collection is difficult.”

- “Our IT department is over-taxed as is and does not have the resources to devote to hosting streaming video files.”

- “We basically had to stop all collection development.”

- “The paradox of increasing production and availability of media resources and shrinking acquisition budgets, due to streaming costs is a disturbing trend, particularly when considering that 100% of our video budget went to DVD acquisitions just four years ago.”

- “(our budget for DVDs) is $20,000 and there’s no way we can purchase in-perpetuity rights for digital files; and, really, there’s no way we can ‘do it all’ or meet all needs.”

- “We love Kanopy – but when it costs $150/year to just provide access, not ownership, to one title, it’s really, really hard to justify.”

- “State legislators are beginning to put pressure on schools to find ways to reduce the cost of things like books, etc.”

- “When colleges and universities are already under fire for the cost of textbooks, etc., asking students to pay one more additional cost gets lumped into the argument about the increasing cost of higher education.”

The concerns these librarians have expressed have been on a slow simmer the last few years but it’s only a matter of time before they hit a full-on pasta boil. One of the most significant concerns, and the one that will affect filmmakers most, is the high cost of streaming.

Another factor that we need to consider is the copyright law and the “Teacher’s Exemption”. With the help of the University of Minnesota, the law is simplified below:

- The Classroom Use Exemption

- Copyright law places a high value on educational uses. The Classroom Use Exemption (17 U.S.C. §110(1)) only applies in very limited situations, but where it does apply, it gives some pretty clear rights.

- To qualify for this exemption, you must: be in a classroom (“or similar place devoted to instruction”). Be there in person, engaged in face-to-face teaching activities. Be at a nonprofit educational institution.

- If (and only if!) you meet these conditions, the exemption gives both instructors and students broad rights to perform or display any works. That means instructors can play movies for their students, at any length (though not from illegitimate copies!)

In other words, if a teacher is going to use the film in their classroom, and they teach in a public university or high school, they do not need anybody’s permission to stream the film to their students.

That’s not the best news for filmmakers but I always say: facts are your friends. Knowing that they won’t need your permission, what can you do to ensure teachers see (and love) your film?

Stay with me because I’m going to ask you to do a little math:

If a librarian has a budget of $20,000 a year for films, at an average cost of $150 for a one-year digital site license (DSL), then they can expect to rent approximately 133 DSLs a year. According to Quora, there are nearly 10,000 films currently being made each year and that number is growing (thanks in large part to technology.) The bottom line is that you have a 1.3% chance that your film will be rented by that university or college. If we increase the library’s budget 5 times, your chance increases to 6.5% which are not great odds.

Facts are our friends. If independent film producers and companies like Outcast Films are going to survive in this volatile business, we need to embrace the facts to solve the problems which means doing your homework. Filmmakers who think they have a great film for the educational market, will have to make their film available through digital platforms. But if they want to increase their odds of selling the film, you will also have to do their own marketing – or hire someone who has experience in the business to help you.

Here are a few tips to help you get started:

- Define and establish your goals as soon as possible

- Write copy for your film with your audience in mind (i.e. teachers are going to want to know how they can use this film in their class)

- Organize a college tour before you turn over the rights of the film

- In the process, find academic advocates who will present the film at conferences AND recommend it to their librarians.

The educational market is a very important audience to reach for many filmmakers. I think most folks reading this blog would agree there is not a better way to educate than by using film. The educational market can also be lucrative, but librarians cannot sustain the increase in costs for steaming over the long haul. As information flows freely through technology, teachers are becoming savvy to the business and realize they don’t need permission to stream a film in their classroom if they respect the criteria set forth in the copyright law.

Remember, facts are our friends. If you think your film is perfect for the educational market, then do your homework: research, strategize and find partners who will help you.

David Averbach August 1st, 2018

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, education, Netflix, Uncategorized

What Nobody Will Tell You About Getting Distribution For Your Film; Or: What I Wish I Knew a Year Ago.

By Smriti Mundhra

Smriti Mundhra is a Los Angeles-based director, producer and journalist. Her film A Suitable Girl premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2017 and is currently playing at festivals around the world, including Sheffield Doc/Fest and AFI DOCS. Along with her filmmaking partner Sarita Khurana, Smriti won the Albert Maysles Best New Documentary Director Award at the Tribeca Film Festival.

I recently attended a panel discussion at a major film festival featuring funders from the documentary world. The question being passed around the stage was, “What are some of the biggest mistakes filmmakers make when producing their films?” The answers were fairly standard—from submitting cuts too early to waiting till the last minute to seek institutional support—until the mic was passed to one member of the panel, who said, rather condescendingly, “Filmmakers need to be aware of what their films are worth to the marketplace. Is there a wide audience for it? Is it going to premiere at Sundance? Don’t spend $5 million on your niche indie documentary, you know?”

Immediately, my eyebrow shot up, followed by my hand. I told the panelist that I agreed with him that documentaries—really, all independent films—should be budgeted responsibly, but asked if he could step outside his hyperbolic example of spending $5 million on an indie documentary (side note: if you know someone who did that, I have a bridge to sell them) and provide any tools or insight for the rest of us who genuinely strive to keep the marketplace in mind when planning our films. After all, documentaries in particular take five years on average to make, during which time the “marketplace” can change drastically. For example, when I started making my feature-length documentary A Suitable Girl, which had its world premiere in the Documentary Competition section of this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, Netflix was still a mail-order DVD service and Amazon was where you went to buy toilet paper. What’s more, film festival admissions—a key deciding factor in the fate of your sales, I’ve learned—are a crapshoot, and there is frustratingly little transparency from distributors and other filmmakers when it comes to figuring out “what your film is worth to the marketplace.”

Sadly, I did not get a suitable answer to my questions from the panelist. Instead, I was told glibly to “make the best film I could and it will find a home.”

Not acceptable. The lack of transparency and insight into sales and distribution could be the single most important reason most filmmakers don’t go on to make second or third films. While the landscape does, indeed, shift dramatically year to year, any insight would make a big difference to other filmmakers who can emulate successes and avoid mistakes. In that spirit, here’s what I learned about sales and distribution that I wish I knew a year ago.

As any filmmaker who has experienced the dizzying high of getting accepted to a world-class film festival, followed by the sobering reality of watching the hours, days, weeks and months pass with nary a distribution deal in sight can tell you, bringing your film to market is an emotional experience. This is where your dreams come to die. A Suitable Girl went to the Tribeca Film Festival represented by one of the best agent/lawyers in the business: The Film Collaborative’s own Orly Ravid (who is also an attorney at MSK). Orly was both supportive and brutally honest when she assessed our film’s worth before we headed into our world premiere. She also helped us read between the lines in trade announcements to understand what was really going on with the deals that were being made – because, let’s face it, who among us hasn’t gone down the rabbit hole of Deadline.com or Variety looking for news of the great deals other films in our “class” are getting? Orly kept reminding us that perception is not reality, and that many of these envy-inducing deals, upon closer examination, are not as lucrative or glamorous as they may seem. Sometimes filmmakers take bad deals because they just don’t want to deal with distribution, have no other options, and can’t pursue DIY, and by taking the deal they get that sense of validation that comes with being able to say their film was picked up. Peek under the hood of some of these trade announcements, and you’ll often find that the money offered to filmmakers was shockingly low, or the deal was comprised of mostly soft money, or—even worse—filmmakers are paying the distributors for a service deal to get their film into theaters. There is nothing wrong with any of those scenarios, of course, if that’s what’s right for you and your film. But, there is often an incorrect perception that other filmmakers are somehow realizing their dreams while you’re sitting by the phone waiting for your agent to call.

Depressed yet? Don’t be, because here’s the good news: there are options, and once you figure out what yours are, making decisions becomes that much easier and more empowering.

Start by asking yourself the hard questions. Here are 12+ things Orly says she considers before crafting a distribution strategy for the films she represents, and why each one is important.

- At which festival did you have your premiere? “Your film will find a home” is a beautiful sentiment and true in many ways, but distributors care about one thing above all others: Sundance. If your film didn’t beat the odds to land a slot at the festival, you can already start lowering your expectations. That’s not to say great deals don’t come out of SXSW, Tribeca, Los Angeles Film Festival and others, but the hard truth is that Sundance still means a lot to buyers. Orly also noted that not all films are even right for festivals or will have a life that way, but they can still do great broadcast sales or great direct distribution business – but that’s a specific and separate analysis, often related to niche, genre, and/or cast.

- What is your film’s budget? How much of that is soft money that does not have to be paid back, or even equity where investors are okay with not being paid back? In other words, what do you need to net to consider the deal a success? Orly, of course, shot for the stars when working on sales for our film, but it was helpful for her to know what was the most modest version of success we could define, so that if we didn’t get a huge worldwide rights offer from a single buyer she could think creatively about how to make us “whole.”

- What kind of press and reviews did you receive? We hired a publicist for the Tribeca Film Festival (the incomparable Falco Ink), and it was the best money we could have spent. Falco was able to raise a ton of awareness around the film, making it as “review-proof” as possible (buyers pay attention if they see that press is inclined to write about your film, which in many cases is more important to them than how a trade publication reviews it). We got coverage in New York Magazine, Jezebel, the Washington Post and dozens of other sites, blogs, and magazines. Thankfully, we also got great reviews in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, and even won the Albert Maysles Prize for Best New Documentary Director at Tribeca. Regardless of how this affected our distribution offers, we know for sure we can use all this press to reignite excitement for our film even if we self-distribute. On the other hand, if you’re struggling to get attention outside of the trades and your reviews are less than stellar, that’s another reason to lower expectations.

- What are your goals, in order of priority? Are you more concerned with recouping your budget? Raising awareness about the issues in your film (impact)? Or gaining exposure for your next project/ongoing career? And don’t say “all three”—or, if you do, list these in priority order and start to think about which one you’re willing to let go.

- How long can you spend on this film? If your film is designed for social impact, do you intend to run an impact/grassroots campaign? And can you hire someone to handle that, if you cannot? Do you see your impact campaign working hand in hand with your profit objectives, or separately from them? The longer you can dedicate to staying with your film following its premiere, the more revenue you can squeeze out of it through the educational circuit, transactional sales, and more. But that time comes at a personal cost and you need to ask yourself if it’s worth it to you. Side note: touring with your film and self-distributing are also great ways to stay visible between projects, and could lead to opportunities for future work.

- Does your film have sufficient international appeal to attract a worldwide deal or significant territory sales outside of the United States? If you think yes, what’s your evidence for that? Are you being realistic? By the way, feeling strongly that your film has a global appeal (as I do for my film) doesn’t guarantee sales. I believe my film will have strong appeal in the countries where there is a large South Asian diaspora—but many of those territories command pretty small sales. Ask your agent which territories around the world you think your film might do well in, and what kinds of licensing deals those territories tend to offer. It’s a sobering conversation.

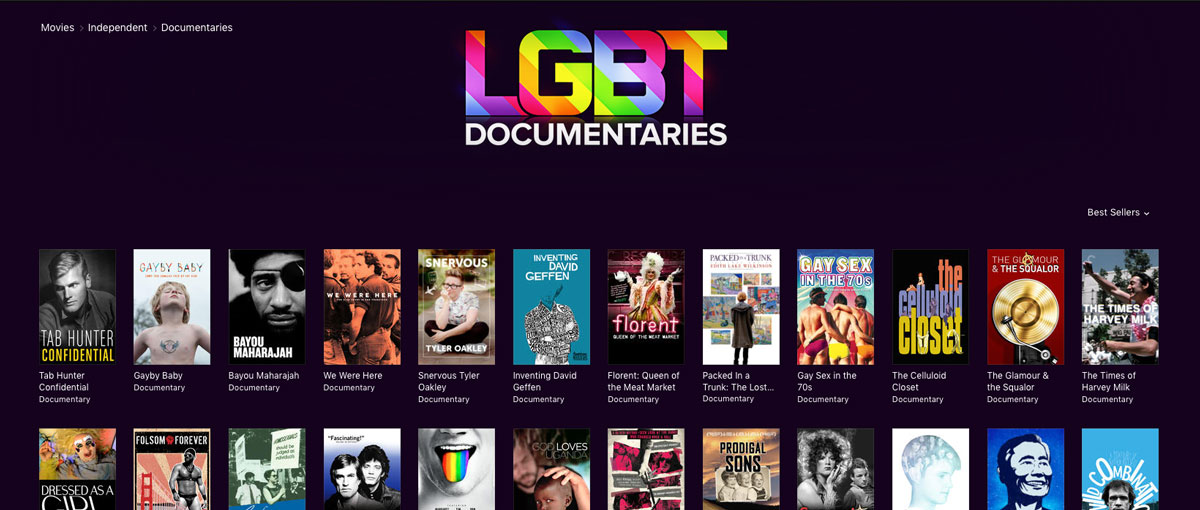

- Does your film fit into key niches that work well for film festival monetization and robust educational distribution? For example, TFC has great success with LGBTQ, social justice, environmental, Latin American, African American, Women’s issues, mental health. Sports, music, and food-related can work well too.

- Does your film, either because of subjects or issues or both, have the ability to command a significant social media following? A “significant” social media following is ideally in the hundreds of thousands or millions of followers, but is at least in the high five figures. We know the last thing you want to think about when you’re trying to lock picture, run a crowdfunding campaign, deal with festival logistics, and all the other stress of preparing for your big debut is social media. But don’t sleep on it. Social media is important not only to show buyers that there is interest in your film, but also ideas on how to position your film and which audiences are engaging with it already. Truth be told, unless you’re in the hundreds of thousands or millions of followers range, social media probably won’t make or break your distribution options, but it can’t hurt. And, in our case, it actually helped us get a lot of interest from educational distributors, who were inspired by the dialogue they saw brewing on our Facebook page.

- How likely is your film to get great critic reviews, and thus get a good Rotten Tomatoes score? Yeah, not much you can do to predict this one. However, a good publicist will have relationships with critics who can give you some insight into what the critical reaction to your film might be, before you have to read it in print. They also reach out to press who they think will like your film, keep tabs on reactions during your press and industry screenings, and monitor any press who attend your public screenings. This data is super useful for your sales representatives.

- How likely is your film to perform theatrically (knowing that very few do), sell to broadcasters (some do but it’s very competitive), sell to SVOD platforms (as competitive as TV), and sell transactionally on iTunes and other similar services (since so many docs do not demand to be purchased)? While these questions are easy to pose and hard to answer, start by doing realistic comparisons to other films based on the subject, name recognition of filmmakers, subject, budget, festival premiere status, and other factors indicating popularity or lack thereof. Also adjust for industry changes and changes to the market if the film you are comparing to was distributed years before. Furthermore, adjust for changes to platform and broadcaster’s buying habits. Get real data about performance of like-films and adjust for and analyze how much money and what else it took to get there.

- Can your film be monetized via merchandise? Not all docs can do this, but it can help generate revenue. So, go for the bulk orders of t-shirts, mugs, and tote bags during your crowdfunding campaign and sell that merch! Even if it just adds up to a few hundred extra dollars, for most people it’s pretty easy to put a few products up on their website.

- Does your film lend itself to getting outreach/distribution grants, or corporate sponsorship/underwriting? With the traditional models of both film distribution and advertising breaking down, a new possibility emerges: finding a brand with a similar value set or mission as your film to underwrite some portion of your distribution campaign. I recently spoke to a documentary filmmaker who sold licenses to his film about veterans to a small regional banking chain, who then screened the film in local communities as part of their outreach effort. The bank paid the filmmakers $1000 per license for ten separate licenses without asking them to give up any rights or conflict with any of their other deals—that’s $10,000 with virtually no strings attached. Not bad!

Sadly, Netflix is no longer the blank check it once was (or that I imagined it to be) and the streaming giant is taking fewer and fewer risks on independent films. Thankfully, Amazon is sweeping in to fill the gap, and their most aggressive play has been their Festival Stars program. If you’re lucky enough to premiere in competition at one of the top-tier festivals (Sundance, SXSW, and Tribeca for now, but presumably more to come), then you already have a distribution deal on the table: Amazon will give you a $100,000 non-recoupable licensing fee ($75,000 for documentaries) and a more generous (double) revenue share than usual per hour your film is streamed on their platform for a term of two years. For many independent films, this could already mean recouping a big chunk of your budget. It also provides an important clue as to “what your film is worth to the marketplace”—$100,000 seems to be the benchmark for films that can cross that first hurdle of landing a competition slot at an A-list festival.

I’ll admit, I was a snob about the Amazon deal when I first heard about it. I couldn’t make myself get excited about a deal that was being offered to at least dozen other films, sight unseen, with no guarantee of publicity or marketing. A Facebook post by a fellow filmmaker (who had recent sold her film to a “legit” distributor) blasting the deal as “just a steep and quick path to devalue the film” left me shaken. But again, appearances proved to be deceiving.

I discussed my concerns with Orly, and she helped me see that with so few broadcast and financially meaningful SVOD options for docs, having a guaranteed significant platform deal with a financial commitment and additional revenue share is actually a great thing. Plus, one can build in lots of other distribution around the Amazon deal and end up with as robust a release as ever there could be. Orly says one should treat Amazon as a platform (online store) but as a distributor and that can provide for all the distribution potential. If one does manage to secure an all-rights deal from a “legit” distributor (we won’t name names, but it’s the companies you might see your friends selling their films to), oftentimes that distributor is just taking the Amazon deal on your behalf anyway, and shaving off up to 30% of it for themselves. So the analysis needs to be what is that distributor doing, if anything, to create additional value that merits taking a piece of a deal you can get on your own? Is it that much more money? Is it a commitment to do a significant impactful release? Are the terms sensible in light of the added value and your recoupment needs? Can you accomplish the same via DIY? Perhaps you can, but don’t want to bother. That’s your choice. But know what you are choosing and why.

Independent filmmakers are, yet again, in uncharted territory when it comes to distribution. Small distributors are closing up shop at a rapid pace. Netflix and Hulu are buying less content out of festivals, and creating more of it in house. Amazon’s Festival Stars program was just announced at Sundance this year (2017) and doesn’t launch until next Spring, so the jury is out as to whether it will really be the wonderful opportunity for filmmakers that it claims to be. By this time next year, several dozen films will have inaugurated the program and will be in a position to share their experiences with others. I hope my fellow filmmakers will be willing to do so. Given the sheer variety of films slated to debut on the platform, this data can be our first real chance to answer the question that the funder on the panel I attended refused to: “What is my film worth to the marketplace?”

Orly adds that the lack of transparency is, of course, in great part attributable to the distributors and buyers, who maintain a stranglehold on their data, but it’s also due to filmmakers’ willful blindness and simple unwillingness to share details about their deals in an effort to keep up appearances. That’s totally understandable, but if we can break the cycle of competing with each other and open up our books, we will not only have more leverage in our negotiations with buyers, but will be equipped to make better decisions for our investors and our careers. Knowledge is power, and if we all get real and share, we’ll all be informed to make the best choices we can.

admin July 5th, 2017

Posted In: Amazon VOD & CreateSpace, Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, education, Film Festivals, Hulu, International Sales, iTunes, Marketing, Netflix, Publicity, Theatrical

7 Proven Strategies for DIY Documentary Fundraising, Distribution and Outreach

by Dan Habib

Dan Habib is the creator of the award-winning documentary films Including Samuel (2008), Who Cares About Kelsey? (2012), Mr. Connolly Has ALS (2017), and many other films on disability-related topics. Habib’s films have been broadcast nationally on public television, and he does extensive public speaking around the country and internationally. Habib’s upcoming documentary Intelligent Lives (2018) features three pioneering young adults with disabilities who navigate high school, college, and the workforce—and undermine our nation’s sordid history of intelligence testing. The film includes narration from Academy award-winning actor Chris Cooper and is executive produced by Amy Brenneman. Habib, who was a photojournalist from 1988-2008, is a filmmaker at the Institute on Disability at the University of New Hampshire.

About 14 years ago, I sat at my son Samuel’s bedside in the ICU as he lay in a medically induced coma. He had developed pneumonia from complications following surgery. Samuel’s neurologist encouraged me to use my skills as a photojournalist in the midst of my fear. “You should document this,” he said. Samuel, who has cerebral palsy, recovered from this emergency, and I took the doctor’s advice. Four years later, I released my first documentary, Including Samuel, which includes a scene from that hospital room. The film aired nationally on public TV in 2009, and we created a DVD with 17 language translations.

Along with the film’s launch, I started discussing my experiences as a parent of a child with a disability at film screenings, which led to a 2013 TEDx talk called Disabling Segregation.

I am now directing/filming/producing my third feature length documentary and am honored that The Film Collaborative asked me to share a few things I’ve learned along the way about DIY fundraising, distribution and outreach.

- Diversify your funding streams.

Although I made Including Samuel on a shoestring while I was still working fulltime as a newspaper photography editor, I’ve been able to raise about $1 million for each of my last two films—a budget which covers my salary and benefits, as well as all production costs. I’ve received essential support from The Fledgling Fund, but the vast majority of my funding comes from sources that don’t typically fund films:- NH-based foundations that are interested in supporting the advancement of the issues I cover in my films (disability/mental health/education).

- National and regional foundations and organizations that focus on tangible outcomes. The Mitsubishi Electric America Foundation is the lead $200,000 supporter of my current project. MEAF funds efforts to increase the employment rates for young people with disabilities.

- Each year I typically take on one outside contract (around $75,000) from a non-profit to create a documentary film short (18-25 min.) on specific disability or education issues. These films have focused on areas like the restraint and seclusion of students or inclusive education , and help me meet my overall budget needs.

- For the last ten years, the most stable source of income has been my speaking fees, which average about $75,000/year and go back into my project budget at UNH. I do about 15 paid speaking gigs per year, and charge $5000 per 24-hours away from home (plus travel expenses). We don’t do any paid advertising—the gigs almost always come from word of mouth (see #5 below).

- Build buzz from the get-go

For some docs, secrecy is essential for editorial reasons, or the filmmaker may just prefer to keep it close to the vest. I’ve never gone that route, because I’ve felt a pragmatic need to build up an audience and donor base early in the project. For each of my films, I’ve cut a 10-14 minute ‘preview’ early in the project’s production (about 2 years before completion), which has been critical for fundraising pitches, generating buzz in social media, and for use in my public speaking presentations.On the temporary website for my Intelligent Lives project, the 14-minute preview is accessible only after completing a name/email sign in form (I also have an unlisted YouTube link to share with VIPs and funders). I’m sure some people have been turned off by this, but more than 6000 people have provided their name and email—which will be a huge asset when we launch a crowdfunding campaign in the fall to complete (I hope!) our production fundraising.Facebook has been the most active and successful platform for reaching our largest audience—educators and families—with Twitter a distant second. For the current project, we have plans to dive into Instagram and other platforms more deeply—primarily with video clips. We also see LinkedIn as a platform that can help us achieve one of the outreach goals for the new film—connecting young adults with disabilities with potential employers through virtual career fairs. - Partner up early

I’ve spent hundreds of hours initiating and developing strong partnerships with national organizations that focus on the issues that my films address. For all three of my documentaries, I’ve held national strategy summits in Washington, DC, to bring together dozens of these National Outreach Partners (NOPs) to help develop a national outreach and engagement campaign to accompany each film (campaigns include I am Norm for Including Samuel and I Care By for Who Cares About Kelsey?) We are currently developing the campaign for the Intelligent Lives film.The NOPs also typically show my docs at their national conferences and blast the word out about key developments in the film’s release (like community screening opportunities). Our relationships with NOPs are reciprocal. We discuss how the films will shine a bright light on their issues; how they can fundraise off of screenings; and how they can use the entire film—or shorter clips that we can provide—to support their advocacy.I plan to continue to explore the vast topic areas of disability and education, and continually build on the partnerships, funders and audiences we have established (while also working hard to make films that are engaging to the general public). - Establish your DIY distribution goals early and stay the course

When I started work on Who Cares About Kelsey?, my documentary about a high school student with ADHD who had a history of homelessness and family substance abuse, I knew I wasn’t going to try for theatrical release, but instead would focus on broadcast, an educational DVD kit and a national community screening campaign. We presented all of our would-be funders and NOPs with a specific set of outreach strategies for the film’s release that were mostly under our control—not reliant on the buzz and opportunities that would come only by getting into a major film festival. For the Intelligent Lives project, my outreach coordinator Lisa Smithline and I have been working towards a broadcast, festivals, an event theatrical and community screening campaign, VOD, online events and other distribution plans. - Speaking of festivals…do college and conference screenings provide more bang for the buck?

I submit my films to the major fests (no luck so far), as well as mid-level and smaller film festivals, and we’ve had dozens of FF screenings (including Woodstock, Sedona, Thessaloniki, Cleveland). I always have a blast when I can be there. But I also start booking and promoting major events around the country at national conferences and colleges early in a film’s life. Although I know these events might jeopardize admission to some prominent film festivals, my experience has been that these conferences and university screenings usually have a significant, lasting impact: high volumes of DVD sales, tremendous word-of-mouth and social media upticks, and more invitations to do paid public speaking (see above). We also try to collect names and email addresses from attendees at every event, so our e-blast list (21,000+) has become a powerful outreach tool for all of my docs. - Jam-pack the educational DVD and website

In addition to the feature length documentary, I typically create a range of short, freestanding “companion” films that I distribute both on the educational DVD kit and also for free (linked through the film’s website but hosted on YouTube and/or Vimeo). I went a bit overboard for Who Cares About Kelsey?, creating 11 mini-films on related topics. But the benefits were multifold: funders loved (and supported) these free resources, the shorter length (10-14 minutes) made them highly useful educational tools, and the free films bring traffic to the website.I also work with national experts in the topic areas covered in the feature length film and mini-films to develop extensive educational material that is packaged with the educational DVD kit. Combined with reasonable price points ($95-$195, depending on the intended audience), we have generated gross sales in the high six-figures for my last two films combined. We also produce an individual DVD, and have been selling VOD through Amazon (very low revenue compared to DVD sales, but given how much the VOD world has changed since I made “Kelsey,” we are looking at different models of online distribution for Intelligent Lives). We primarily self-distribute these products through the UNH Institute on Disability bookstore, which keeps the profits close to home. - Seek professional help

I maintain a small field production crew (just me and an audio engineer), but my production and distribution budgets are still tight. So I’m grateful for people like Chris Cooper, Amy Brenneman and the musician Matisyahu who are donating their time and creative talents to my latest project. But there is still plenty of specialized talent I need to hire—whether it’s for editing, music scoring, fundraising, graphic art, website design and outreach consulting. And for Intelligent Lives, I’m planning to work with a distribution consultant and sales agent(s).I look for collaborators who share my values and vision that films can be a catalyst for advancing human rights…but they’ve still got to get paid!Return to strategy #1.

Dan Habib can be contacted at dan.habib@unh.edu, @_danhabib, facebook.com/dan.habib, and on Instagram at danhabibfilms.

admin June 28th, 2017

Posted In: Distribution, DIY, education, Uncategorized

Tags: American independent film, Amy Brenneman, Dan Habib, DIY film distribution, documentary films, documentary outreach, DVD distribution, educational distribution for films, film distribution, Fledgling Fund, Lisa Smithline, The Film Collaborative

Low Down on Educational Distribution:

Part 3 of a 3-Part Series

by Orly Ravid, Founder, The Film Collaborative and Attorney, Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP)

The following the final part of a three-part series on Educational Distribution. Part 1: “Get Educated About Educational Distribution,” by Orly Ravid, Founder, The Film Collaborative • February 18, 2016. Part 2: “Fair Use Is Not Fair Game,” by Jessica Rosner, Media Consultant & Orly Ravid, Founder, The Film Collaborative, Attorney, Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP • June 1, 2016. It was offered as a handout at the Low Down on Educational Distribution Panel that took place as part of the SXSW Film Festival on March 12, 2017.

Educational distribution is often part of “Non-Theatrical” rights and generally refers to distribution to schools and libraries (not film festivals, airlines, ships, or hotels, for example). Traditional educational distribution is focused on educational institutions at the university and K-12 level. It can also cover private organizational and corporate screenings. It can involve both physical media (DVDs/Blu-rays) either sold or rented and streaming (via licenses for a term, typically 1-3 years). Not all educational distributors cover the same turf or have the same business models. Below is a summary of some companies and how they define and handle educational distribution. You’ll notice differences and a range of what the companies do within the space. This document also covers revenue ranges, technology differences and industry changes, use of middlemen, best practices, and release examples. I often use the company’s own words to explain how they work. I did not interview filmmakers who have worked with the panelists or other companies, and always recommend checking references and asking around. For any follow-up questions please feel free to contact the distributors or panel moderator Orly Ravid.

Educational Distribution: What is it?

Companies explain their take on educational distribution:

Alexander Street: Offers both streaming and DVD options across its catalog. Focus is on institutional selling and providing both university librarians and university faculty with options ranging from single title streaming and DVD, to demand-driven models and wide access to packages of 60,000 or more titles.

Kanopy: We define educational distribution as sharing important stories with the next generation. Films have the power to engage and challenge like no other medium, and with students watching more film than any other resource, it’s more important than ever before that these films reach this important demographic. We take our relationships with the college librarians very seriously as they are our paying customers and work tirelessly to understand and promote Kanopy to their patrons.

We are lucky to work with such a progressive market of librarians that believed in our new model, Patron Driven Acquisition, whereby libraries only pay for what is watched. This model is now the benchmark for libraries globally and has revolutionized the industry by promoting educational streaming as a viable channel for filmmakers while offering excellent ROI for libraries.

Passion River: Selling or licensing public performance rights for films to schools, colleges, libraries, and community centers/organizations.

Ro*co Films: Distributing content (in our case, top-tier documentary films) to schools, organizations, and corporations for instructional and/or screening purposes.

Outcast Films: Sales and rentals on campuses, academic conferences, campus activities and student film festivals. There are times when we also partner with non-profit organizations both on and off campus. We want to work in collaboration with filmmakers and their outreach efforts to maximize opportunities so we can be flexible. Because the educational market is our only focus, we believe we are the best to handle and coordinate.

The Video Project: ‘Educational and Institutional’ market means all schools, home schools, school districts, offices of education, learning centers, education and research institutions, colleges and universities, libraries, NGOs, nonprofit organizations, corporations, government agencies and offices.

Collective Eye: Thinks of Educational Distribution as any film media sales and licensing made for educational intent. Collective Eye Films is very clear in defining rights to carry a film as certain types of Products; these are generally products that include Public Performance Rights (defined in the below link), Campus & Community Screening Licenses, Public Library licenses and Educational Streaming licenses. Collective Eye covers the traditional educational institutions and offers PPR licenses to non-profits and Government agencies. The company finds that “Community Screening” licenses are very beneficial to filmmakers. Because we are non-exclusive we always discuss the filmmakers’ rights and how our distribution would or would not impact their other distribution deals already in place. Public Libraries as a media right generally come within Home-Entertainment markets, so Collective Eye carries these as a service to filmmakers that do not have other home-entertainment distribution. Since we are non-exclusive we can also provide this as a product alongside another non-exclusive home-use distributor if amenable to both parties. A full list of how we define our licensing types can be found here: http://www.collectiveeye.org/pages/film-licenses.

Summary Info About the Panelists and Other Educational Distributors in Their Own Words:

What They Do in The Educational Distribution Space, and An Estimate of How Much of Their Company’s Business Is Educational Distribution