Fair Use Is Not Fair Game:

Part 2 of a 3-part Series

by Jessica Rosner (Media Consultant) and Orly Ravid (Founder, The Film Collaborative and Attorney, Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp LLP)

This month’s blog is co-written by Jessica Rosner, who has been a film booker in the theatrical, nontheatrical and educational markets since the days of 16mm. Recent titles include Jafar Panahi’s THIS IS NOT A FILM and John Boorman’s QUEEN AND COUNTRY.

One area of film revenue that is both increasing exponentially but often neglected by rights holders is the educational streaming market, which basically allows institutions to stream films to students for classes. Old models of showing films during classes or having students watch copies in the library are being largely overtaken by instructors wanting students to watch films wherever they are from a dorm room to a Starbucks. Unfortunately, while tens of thousands of films, both feature and educational, are being legally streamed, there are others that are being illegally streamed and many thousands that rights holders are not making available. In both cases revenue is being lost. Major rights holders represented by the MPAA have been overreaching by attempting to prevent academic use of clips from DVDs. And, they are ineffectual by refusing to directly challenge claims by some academic institutions and organizations, including the American Library Association, that they can stream an entire film without a license.

Films ranging from shorts produced for the educational market to feature films from studios have been used in classes for decades, first largely in 16mm (rented or purchased from rights holders) and then in a variety of video and digital formats. When videos started in the 1970s a special provision of the copyright law known as the “face-to-face” teaching exemption was enacted that allowed any legally produced video (and later DVD) to be shown to students in physical classrooms supervised by an instructor. (U.S.C. § 110 “Limitations on exclusive rights: Exemption of certain performances and displays”). Few instructors now want to use class time to show films and few students want to go to the library to view or check out physical copy of a film so streaming has become the most popular way to use films for classes. There are many platforms and companies which are servicing this growing market, notably Swank, which handles many of the major studios, and a few that handle independent films, such as Kanopy, Alexander Street Press, Films Media Group, and, for documentaries, Docuseek2. While the vast majority of streaming films done legally through licensed platforms or contracts, there is a segment of the academic community including many influential institutions and organizations which have asserted that under “fair use” they can stream entire films without paying right holders. “Fair use”1 is a long established part of American copyright law which allows portions of copyrighted works to be used in a variety of contexts including education, satire and creating new works. (U.S.C. § 107 “Limitations on exclusive rights: Fair use.”)

In 2010, UCLA (Regents of the University of California) was caught streaming thousands of films from studio features to documentaries, they used in classes without any payment or license to rights holders. When sued by Ambrose Video Publishing (an educational video producer) and the Association for Information Media and Equipment (a consortium of educational media companies) for unlawful copying and reformatting DVDs of BBC productions Shakespeare’s plays and putting them online for students (on UCLA’s own system), the case was initially dismissed due to issues involving lack of standing (Ambrose was not the rights holder) and sovereign immunity. UCLA’s claim that streaming an entire film was acceptable under “fair use” was never actually fully litigated. See Ass’n for Info. Media & Equip. v. Regents of the Univ. of California, No. CV 10-9378 CBM MANX, 2011 WL 7447148, at *1 (C.D. Cal. Oct. 3, 2011); Ass’n for Info. Media & Equip. v. Regents of the Univ. of California, No. 2:10-CV-09378-CBM, 2012 WL 7683452, at *11 (C.D. Cal. Nov. 20, 2012). UCLA also had streamed hundreds of major studio films not included in the lawsuit. The court noted in 2012 that “no Court has considered whether steaming videos only to students enrolled in classes constitutes fair use, which reinforces the ambiguity of the law in this area.” Although no precedent was set by this case because it was dismissed, the failure of other rights holders to challenge this has left their films vulnerable to the claim that streaming an entire feature film for a class is “fair use.”

However recent decisions involving publishers rejected the legal claim that putting an entire work online for a class is “fair use.” In both the Google Books and Georgia State cases, Federal courts ruled that only portions from “snippets” to chapters could be posted online for academic use not an entire book.2

On October 27 the Library of Congress issued an update to Digital Millennium Copyright Act which is the key law on copyrights of digital materials. It allowed far broader access by the academic and non-profit community to numerous digital formats for a variety of “fair use” activities over the strong of objections of the MPAA which had not wanted to allow the breaking up encryption even for legitimate “fair use” such as clips. However, the Library of Congress flatly and clearly rejected the request of representatives of the educational community to be allowed to access entire works stating it was “declined due to lack of legal and factual support for exemption. ”

Despite the recent court rulings and the new DMCA rules, various educational institutions and organizations continue to assert that entire films can be streamed without permission or payment to rights holders. One of the more novel claims is that since feature films were made for “entertainment” and they are now being solely used for “education,” thus transforming their use to qualify as “fair use.” The latter claim is without precedent and directly contradicts numerous precedents in copyright cases that creative works are given a higher level of fair use protection than factual works. E.g. Cambridge Univ. Press, supra, 769 F.3d at1268; Sony Corp. of Am. v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417, 497, 104 S. Ct. 774, 816, 78 L. Ed. 2d 574 (1984). Moreover, such a claim would then justify scanning and streaming online a swath of modern fiction books used for courses.

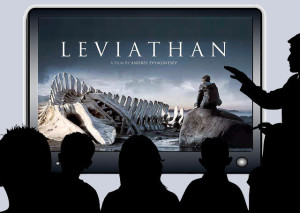

It is crucial for distributors and filmmakers to engage the academic community to protect their rights. It is equally important that they make their films available for legal streaming. Many colleges are frustrated because they are trying to pay and legally license the material only to find that, while a title is available on DVD and some digital platforms, they can’t license that same title for use by students in classes via streaming. Most schools would prefer to license a title directly to ensure availability and not force students pay for Netflix, Amazon, and Hulu memberships even if film is available on those services. Some substantial libraries from Sony Pictures Classics, HBO and a variety of small distributors and individual filmmakers have not allowed their films to be available for streaming by universities. Not being able to access Leviathan, Still Alice, 4 Little Girls, etc. via direct streaming is a major problem for educational institutions. While the license for an individual film to one school might only be $100-$200, there thousands of potential institutions for a wide variety of films. Streaming of feature films for educational use is only going to keep growing.

The film community, from distributors to producers, needs to work with the academic community to make sure all films are directly available to students via their school in the highest quality streaming formats, while also ensuring that rights holders are fairly compensated.

Notes:

1The U.S. Copyright Office has now launched its “fair use” index—a (free) searchable database of U.S. court opinions on copyright fair use dating back to Folsom v. Marsh (1841)…

Here is their description of the database:

Welcome to the U.S. Copyright Office Fair Use Index. This Fair Use Index is a project undertaken by the Office of the Register in support of the 2013 Joint Strategic Plan on Intellectual Property Enforcement of the Office of the Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator (IPEC). Fair use is a longstanding and vital aspect of American copyright law. The goal of the Index is to make the principles and application of fair use more accessible and understandable to the public by presenting a searchable database of court opinions, including by category and type of use (e.g., music, internet/digitization, parody).

Here is the link to the Fair Use Home Page.

And here is the actual link to the Searchable Case Database—you can filter it by federal circuits and/or by types of works (literary works, films etc.).

2 See Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., No. 13-4829-CV, 2015 WL 6079426, at *20 (2d Cir. Oct. 16, 2015) (Second Circuit affirming the finding of fair use as to Google’s unauthorized digitizing of copyrighted works, creation of a search functionality and “display of snippets” because the “purpose of the copying is highly transformative, the public display of text is limited, and the revelations do not provide a significant market substitute for the protected aspects of the originals” and that Google is providing digitized copies to libraries that had the books with the understanding that the libraries will follow copyright law.) See also Cambridge Univ. Press v. Patton, 769 F.3d 1232, 1283 (11th Cir. 2014) (three publishers sued Georgia State University for scanning and posting portions of books and journals for students to access via the university’s e-reserves; Eleventh Circuit reversed and remanded, instructing the lower court to apply the fair use factors more holistically and give more weight to the threat of market substitution). The case (still partly on appeal) is important because it maintains that only a portion of a work may be digitized for fair use.

Orly Ravid June 1st, 2016

Posted In: Legal