DCP failure rate is extraordinarily high. Should you make one?

In two prior posts, I chronicled how rapid technological change was impacting the exhibition side of independent film, and how this was affecting filmmakers and their post-production and delivery choices. In January 2013, in a post called “The Independent’s Guide to Film Exhibition and Delivery” I discussed the rise of the DCP in independent exhibition, and the potential dangers it posed to filmmakers on a budget. And later that year, I posted “Digital Tape is Dead” in which I gave further evidence that it was possible to resist the rise of DCP…at least for the time being… and the reasons for doing so.

photo credit: Bradley Fortner via photopin cc

It’s a little over a year later, so I am returning to the topic to take stock of what a difference another year makes. And as always, the main goal of this exercise is to help you, as filmmakers, to make the best post and delivery choices in finishing and exhibiting your films.

Of the many things that The Film Collaborative does, one of our core services is booking our clients’ and members’ films in public venues all over the world – including everything from film festivals, traditional theatrical venues, universities, art galleries, etc. Every year, this work hits a peak frenzy in October, which is unquestionably THE month of the year with the largest number of film festivals. By simply comparing our booking format totals from October 2013 to October 2014, I can see that once again the landscape of booking has evolved substantially in the last 12 months.

BOOKINGS IN OCTOBER 2013 (total 195 booking engagements):

BLURAY: 144

DVD: 25

DCP: 12

HDCAM: 10

Digibeta: 2

Quicktime File: 2

BOOKINGS IN OCTOBER 2014 (total 268 booking engagements)

BLURAY: 162

DCP: 84

DVD: 12

HDCAM: 6

Quicktime File: 4

Other than the fact that we are obviously a busy company (!), the main takeaway here is that the DCP’s slow and seemingly inevitable rise to the top is continuing, although the actual majority of venues (especially in the U.S.) are still trying to cut costs by the use of BluRay. In Europe, the DCP has already overtaken all other formats, and is nearly impossible to resist if you want to play in any reputable festivals or venues. And after DCP and BluRay, all other formats are now nearly dead worldwide, at least for now.

There are many reasons why this isn’t good news for independent filmmakers (which we’ll go into)…but the first and most obvious problem is that all of the filmmakers we work with are still making multiple HDCAMs! From the data above it is clear, STOP MAKING HDCAMS PEOPLE! I know many companies that have stopped producing them entirely, and are providing only on DCP, BluRay, and DVD.

Usually, an independent filmmaker’s first worry about DCPs is the initial price – indeed it is the most expensive exhibition format to make since the 35mm print. However, the good news is that it has already dropped in price quite a bit from 2013…now if you look around you are sure to be able to get an initial one made for $1,000 – $1,500 (compared to around $2,500 a year ago).

Now there is the really weird situation with the subsequent DCPs…and what you should pay to make additional copies. If you’ve seen DCPs, you’ll know that they often come in these elaborate and heavy “Pelican Cases” with a “Sled” hard drive with USB adaptors and power supplies. That’s the kind the studios use, and they will usually run you around $400 per additional DCP…which is expensive.

The strange thing is that every tech-savvy person I know tells me that this is all window-dressing, and that a regular “Office Depot style drive” USB 3 Drive for $100 serves exactly the same purpose and is actually a bit more reliable since it has less moving parts. Add to this the simple charge for copying the DCP (for which our lab charges only $50), and you’ve got subsequent DCPs at only $150 each…which of course is even cheaper than old tape-based formats like HDCAM and Digibeta.

If someone out there knows why one SHOULDN’T go with the more inexpensive option, I’m all ears. Call me, tweet us @filmcollab, leave a comment on our Facebook page! ‘Cause I haven’t heard it yet.

Of course, its still not a super-cheap $10 BluRay, but the truly annoying thing about the DCP and all its solid state technology and its fancy cases is that it is HEAVY, surpassing everything except old 35mm prints in weight. As a result, the cost of SHIPPING becomes a major issue for independents, and more than $100 every time you send since you obviously aren’t going to put your pristine file in regular mail. If you’ve been booking and playing films for a long time, you’ll know that $100 in shipping is often the difference between a profitable screening a not-so-profitable one…and so the cost adds up quickly.

It’s truly the cost of shipping that makes me sad that the BluRay is doomed as a major exhibition format. At one point, when filmmakers and distributors made “P&A” assessments for their films, the biggest cost in the “P” analysis was the cost of shipping heavy prints. For a brief and shining moment….from like mid 2013 to mid 2014… the lightweight BluRays took that part of the “P” out of the equation entirely…and that sure was nice.

But the (dirty and secret) truth is that COST isn’t the main problem with DCP. It is the RELIABILITY of the format. The horrible fact is that DCP is the most unreliable format in terms of playability that we have ever had….bar none that I can think of. BluRays used to have the reputation for failing often, but they were easy to include a back-up copy with, and they have drastically improved in the last two years such that they almost never fail. DCPs, however, now fail ALL THE TIME, at an alarming rate, and for an alarming number of reasons.

Rather than go into the deep tech-geek reason for DCP failures in venues all over the world…I am going to copy a few recent emails from labs, festivals, and venues I have been communicating with in the last couple of weeks. I promise you…all of this is just in the last two weeks! And all of these are all different films and different DCPs!

[EXAMPLE] On September 16th, XXXX wrote:

So, bad news guys, we couldn’t access the hard drive on this DCP, so it’s our thoughts that it is dead.

[EXAMPLE} On September 18th, XXXX wrote:

Nothing over here is recognizing this DCP. The drive appears to be EXT3 formatted and I think this may be why it’s not recognizing as a usable hard drive. Generally, we use NTFS and EXT2 formatted drives. This one does have a bluray backup, but if you can try to get us another DCP, that’d be cool.

[EXAMPLE} On September 17th, XXX wrote

We just got the DCP and the sled was loose and the final screw holding it came off. It’s the plastic thing that pops out. Just now I noticed that most of the screws on it are loose. It won’t play because I think we need to replace the screws?

[EXAMPLE} On September 22,, XXXX wrote

We are facing difficulties with the DCP as our Server does not seem to recognize the drive. We have spoken to your lab and we think it’s because our server cannot recognize Linux Files. We have about 100 DCPs in our festival, and this is happening to about 10 of our films. Can you offer any advice?

It is this last example that really cracks me up….if you happen to know anything about DCP you know that Linux was chosen as the best format for DCI-complaint files. So the fact that a festival could not read Linux, but could still read 90 out of 100 of their DCPs is absolutely mid-boggling, as I thought Linux was in fact the common denominator.

But I digress.

As filmmakers, is any of this what you want to be doing with your time? Do you really want to know about EXT3 and EXT2, and do you seriously want to worry about replacing loose screws on a drive? Do you want to reduce your whole filmmaking experience as to whether a venue can read Linux or not? Do you have time for this?

Just this weekend, we had a screening in North Hollywood where the sound on the DCP went out for the last 5 minutes of the film, all the way through the credits. Is this acceptable? I thought not.

It was better before. We don’t like to think that evolution is like this….getting worse rather than better….but in truth it often is. And this is one of those times.

The truth is, I will never trust this format. The DCP was created by a 7-member consortium of the major multinational studios called the Digital Cinema Initiative (DCI). It represented only the major studios…and created a format best suited to their needs. They have since adapted all the major venues to their needs. Is it any wonder that these needs do not represent the needs of independent filmmakers? Do we have any doubt that that any “consortium” would actively seek to suppress the needs of its competition? It created encryption codes only they can functionally work with. It put all the rest of us in danger, in my opinion. Let’s just talk about their unworkable encryption technology if we want to start somewhere. KDMs on independent films are a joke….leaving us more vulnerable to piracy than ever.

So, here is why the “P” matters more than ever. And why there is still GREAT reasons to hope. Just when you thought I was writing a depressing post, I am going to flip this b*itch. And I mean “b*itch” in the best manner possible.

The truth is…the age of cloud based computing, the no shipping, the no P in “P&A” reality is finally nearly upon us.

The truth is…it will not be long before we can use cloud-based services to deliver our films to venues all over the world. Of course, it is happening now….but it is not a mature system yet. But my guess is that it WILL be very soon. Definitely less than 5 years.

With all the new services like Google Drive, WeTransfer, DropBox, Vimeo, etc all rapidly evolving…..we are only months (if not years) from really delivering our films without help from middle men like Technicolor and FED EX. And that will be a good thing. A great thing really. I believe it will increase our indie profits many fold.

Already, every single day, I have numerous festivals asking me to DropBox them the films we are working with. In truth, I haven’t figured out really how to do that yet in quality levels I am comfortable with that also make financial sense. I am in constant dialogue with our lab and our tech people as to how to make this work in terms of uploading time, server space, and quality of presentation.

But it is clear to me that it IS happening over time….if anyone knows the secrets…again, I am ALL ears! Please call me! Because I truly believe that when we can remove the P from the P&A equation….and I mean truly remove it such that any number of prints and all shipping can be eliminated as easily as sending someone a link to an FTP or whatever…..we will re-enter an age where independent film distribution will make real financial sense. Imagine that, for a moment.

And the weirdest thing is I think it is truly happening… any day now.

NOTE: Step 4 in this blog series will be an analysis of how to deliver your film digitally and via The Cloud. We aren’t there yet….BUT that is what I will cover in the next post of this series. Hopefully new updates will happen by the end of the year!

Jeffrey Winter October 1st, 2014

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, DIY, Film Festivals, Theatrical

Tags: BluRays, DCP, DCP failure rate, Digital Cinema Package, DVD, film festival distribution, HDCam, Jeffrey Winter, Quicktime, The Film Collaborative, theatrical distribution

Distribution preparation for independent filmmakers-Part 3 Terms, foreign and windows

By Orly Ravid and Sheri Candler

In the past 2 posts, we have covered knowing the market BEFORE making your film and how to incorporate the festival circuit into your marketing and distribution efforts. This post will cover terms you need to know; whether a foreign distribution agreement is in your film’s future and what to do if it isn’t; the patterns, or windows, that need to be considered in your release. Just to be clear, we are targeting these posts mainly to filmmakers who seek to self finance and actively control their distribution. If that is not your plan, the usefulness of these posts may vary.

Distributors; platforms; aggregators; self hosting sites; applications

If you are new to the distribution game, here are some terms you now need to be familiar with.

Distributors (ie. A24, Oscilloscope, Fox Searchlight, Sony Classics, The Weinstein Company, Roadside Attractions) take exclusive rights to your film for a negotiated period of time and coordinate its release. These companies often acquire independent films out of the most prestigious film festivals and pay decent advances for ALL RIGHTS, sometimes even for ALL TERRITORIES. A signed and binding contract takes all responsibility for the film away from its creator and places it with the distributor to decide how to release it into the public. Distribution through these entities entails theatrical, digital, DVD, educational, leisure (airline/hotel/cruiseship).

Platforms (ie. iTunes, Amazon Prime, Google Play, Hulu, Netflix, cable VOD) are digital destinations where customers watch or buy films. Viewing happens on a variety of devices and some allow for worldwide distribution. Mainly platforms do not deal directly with creators, but insist on signing deals with representative companies such as distributors or aggregators.

Aggregators (ie. Premiere Digital, Inception Media Group, BitMAX, Kinonation) are conduits between filmmakers/distributors and platforms. Aggregators have direct relationships with digital platforms and often do not take an ownership stake. Aggregators usually focus more on converting files for platforms, supplying metadata, images, trailers to platforms and collecting revenue from platforms to disperse to the rights holder. Sometimes distributors (Cinedigm, FilmBuff) also have direct relationships with digital platforms, helping reduce the number of intermediaries being paid out of the film’s revenue.

Self hosting sites (ie. VHX, Distrify, Vimeo on Demand) are all services that allow filmmakers to upload their films and host them on whatever website they choose. Vimeo on Demand also hosts the video player on its own central website and has just integrated with Apple TV to allow for viewing on in-home TV screens.

Applications for many digital platforms can be found on mobile devices (smartphones and tablets),Over the Top (OTT) internet-enabled devices like Roku, Chromecast, Apple TV, Playstation and Xbox and on smart TVs. Viewers must add the applications to their devices and then either subscribe or pay per view to the platforms in order to see the film.

What about international?

In the latest edition of our Selling Your Film book series, Amsterdam based consultant Wendy Bernfeld goes into great depth about the digital distribution market in Europe. Many low-budget, independent American films are not good candidates for international sales because various international distributors tend to be attracted to celebrity actors or action, thriller and horror genre fare that translate easily into other languages.

Rather than give all of your film’s rights to a foreign sales agent for years (often 7-10 years duration) just to see what the agent can accomplish, think seriously about selling to global audiences from your own website and from sites such as Vimeo, VHX, Google Play and iTunes. The volume of potential viewers or sales it takes to attract a foreign distributor to your film is often very high. But just because they aren’t interested doesn’t mean there is NO audience interest. It simply means audience interest isn’t high enough to warrant a distribution deal. However, if you take a look at your own analytics via social media sites and website traffic, you may find that audience interest in foreign territories is certainly high enough to warrant self distributing in those territories. Look at this stats page on the VHX site. There are plenty of foreign audiences willing to buy directly from a film’s website. Why not service that demand yourself and keep most of the money? Plus keep the contact data on the buyers, such as email address?

Often, sales agents who cannot make foreign deals will use aggregators to access digital platforms and cut themselves into the revenue. You can save this commission fee by going through an aggregator yourself. In agreements we make with distributors for our Film Collaborative members, we negotiate for the filmmaker to have the ability to sell worldwide to audiences directly from their website. If you are negotiating agreements directly with distributors, the right to sell directly via your own website can be extremely beneficial to separate and carve out because sales via your website will generate revenue immediately. However, this tactic is now being scrutinized by distributors who are allowing direct to audience sales by filmmakers, but asking in their agreement for a percentage of the revenue generated. It is up to the filmmaker to decide if this is an acceptable term.

If you do happen to sell your film in certain international territories, make sure not to distribute on your site in a way that will conflict with any worldwide release dates and any other distribution holdbacks or windowing that may be required per your distribution contracts. An example: You have signed a broadcast agreement that calls for a digital release holdback of 90 days-6 months-1 year or whatever. You cannot go ahead and start selling via digital in that territory until that holdback is lifted. Instead, use a hosting service that will allow you to geoblock sales in that territory.

Know your windows.

If you do decide to release on your own, it’s important to know how release phases or “windows” work within the industry and why windowing was even created.

The release window is an artificial scarcity construct wherein the maximum amount of money is squeezed from each phase of distribution. Each window is opened at different times to keep the revenue streams from competing with each other. The reason it is artificial is the film continues to be the same and could be released to the audience all at one time, but is purposely curbed from that in order to maximize revenue and viewership. The Hollywood legacy window sequence consists of movie theaters (theatrical window), then, after approximately 3-4 months, DVD release (video window). After an additional 3 months or so, a release to Pay TV (subscription cable and cable pay per view) and VOD services (download to own, paid streaming, subscription VOD) and approximately two years after its theatrical release date, it is made available for free-to-air TV.

Now, there is a lot of experimentation with release windows. Each release window is getting shorter and sometimes they are opened out of the traditional sequence. Magnolia Pictures has pioneered experimentation with Ultra VOD release, the practice of releasing a film digitally BEFORE its theatrical window and generally charging a premium price; and with Day and Date, the practice of releasing a film digitally and theatrically at the same time. Many other distributors have followed suit. Radius-TWC just shortened the theatrical only window for Snowpiercer by making it available on digital VOD within only 2 weeks of its US theatrical release. During its first weekend in US multiplatform release, Snowpiercer earned an estimated $1.1 million from VOD, nearly twice as much as the $635,000 it earned in theaters.

So, while there are certainly bends in the rules, you will need to pay attention to which release window you open for your film on what date. For example, it might be enticing to try to negotiate a flat licensing fee from Netflix (Subscription VOD or SVOD window) at the start of release. However, from a filmmaker’s (and also distributor’s) perspective, if the movie has not yet played on any other digital platforms, it would be preferable to wait until after the Transactional VOD (TVOD) window in order to generate more revenue as a percentage of every TVOD purchase, before going live on Netflix. If the transactional release and subscription release happen at the same time, it cannibalizes transactional revenue.

Also, sites like Netflix will likely use numbers from a film’s transactional window purchases to inform their decision on whether to make an offer on a film and how big that offer should be. Subscription sites such as Netflix also pay attention to general buzz, theatrical gross, and a film’s popularity on the film’s website. There is value in gathering web traffic analytics, email database analytics and website sales data in order to demonstrate you have a sizable audience behind your film. This is useful information when talking to any platform where you need their permission to access it. Caution: Netflix is not as interested in licensing independent film content as it once was. If your film is not a strong performer theatrically, or via other transactional VOD sites; does not have a big festival pedigree; or does not have notable actor names in it, it may not achieve a significant Netflix licensing fee or they may refuse to license it for the platform. Netflix is no longer building its brand for subscribers and it has significant data that guides what content it licenses and what it produces.

Also be aware that some TV licensing will call for holding back Subscription VOD (SVOD) releases for a period of time. If your film is strong enough to achieve a broadcast license deal, you will need to wait before making a subscription release deal. On the other hand, holding out too long for a broadcast distribution offer might cause the publicity and interest you’ve generated for your film to dissipate.

If your film is truly a candidate for theatrical release, most cinemas will not screen a film that is already available on TVOD or SVOD services. In fact, most of the chain cinemas will not screen a film that is available in any other form prior to or at the same time as theatrical release.

The way you choose to release your film is a judgment call in order to reach your particular goal. All decisions have consequences and you will have to live with the decisions you make in releasing your film. Like all decisions, you base them on what you know at the time with no guarantee as to how they will turn out.

Sheri Candler July 16th, 2014

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distribution Platforms, DIY, International Sales, Theatrical

Tags: aggregators, Distrify, independent film distribution, Orly Ravid, release windows, Sheri Candler, SVOD, The Film Collaborative, theatrical distribution, TVOD, VHX, Vimeo on Demand, Wendy Bernfeld

Our partnership with Devolver Digital and Humble Bundle

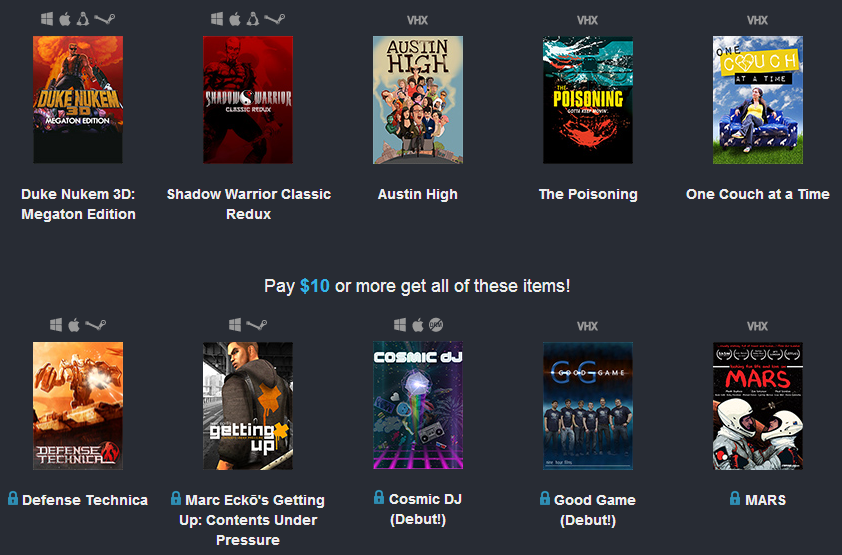

You may remember that I profiled a new digital distributor last year called Devolver Digital who was adding independent films to their existing line up of video games. Yesterday, Devolver announced a new initiative with the folks at Humble Bundle and VHX to release the “Devolver Digital Double Debut” Bundle, a package that includes five games both classic and new and the new documentary Good Game profiling the professional gaming lives of the world-renown Evil Geniuses clan as well as other films on the VHX platform. Proceeds from the bundle benefit the Brandon Boyer Cancer Treatment Relief Fund as well as The Film Collaborative.

You may remember, we are a registered 501c3 non profit dedicated to helping creators preserve their rights in order to be the main beneficiary of their work. We plan to use our portion of the proceeds to fund the new edition of our book Selling Your Film Without Selling Your Soul which will be given away totally free upon its publication. If you’ve ever benefited from our advice, our speaking or our written posts, now is the opportunity to give us support in expanding even more of your knowledge as well as help Brandon Boyer, chairman of the Independent Games Festival (IGF), to help with his astronomical medical bills for cancer treatment.

You can find the Bundle here https://www.humblebundle.com/

It is just this kind of out of the box thinking we love and we couldn’t wait to be involved.

As a follow up to last year’s piece, I asked Devolver Digital founder, Mike Wilson, to fill me in on how the company has ramped up and what this initiative means to gamers, to filmmakers and to the non profits involved.

In the year since Devolver Digital started, how has your games audience transitioned into an audience for the films you handle?

MW: “When we announced the start the Films branch of Devolver Digital last SXSW, we did so for a few reasons. The first was seeing an opening to create a more publishing-like digital distributor for micro-indies. Curation, promotion, transparency, versus what we perceived as the status quo in the VOD distribution space where films were uploaded in bulk and they hope for the best.

One of the biggest reasons, though, was the knowledge that the biggest games platforms that we do 95% of our (very healthy) digital distribution business with on the games side were going to be moving to start delivering films this year. Those platforms are still not very active in the film space, aside from Games/Movies bundle with Humble Bundle that just kicked off. But they are coming, so we’ll know more about how much we are able to turn the indie game-loving audience onto indie films from the fest circuit a little later this year. Our hopes remain high, as these are people who consume an inordinate amount of digital media, are very comfortable with digital distribution and watching films on their computers, and they have a community around independent content from small teams around the world like nothing we’ve seen on the film side. It’s more akin to music fans, turning friends on to great bands they’ve never heard of, and gaining their own cred for unearthing these gems. THIS is what we hope to finally bring to the independent film space, along with these much more sophisticated platforms in terms of merchandising digital content.”

Where are you seeing the greatest revenues from? Cable VOD, online digital, theatrical? Even if one is a considered a loss leader, such as theatrical typically, does it make sense to keep that window?

MW: “We just started releasing films on cable VOD in the Fall, and most of that content didn’t hit digital until recently, so the jury is still a bit out. We are now able to do day-and-date releasing on all platforms as well. We have done limited theatrical, purely as a PR spend on a couple of our strongest releases, and that has been very successful in terms of getting press the films never would have gotten otherwise, but of course it does cost some money and it’s just an investment in the VOD future of the films. There is still no hope of breaking even on a theatrical run for indies as far as we can tell… but at least the cost to entry has gone down and will hopefully continue to do so. For now, we still expect cable and iTunes to be our best performers, until the games platforms start delivering.”

What lead to this recent initiative through Humble Bundle and VHX? Have you partnered with them before?

MW: “Humble Bundle has been a miraculous success on the indie games side. We do bundles with them as often as possible. The key was getting them and VHX to work together, as we needed a high-quality, low-cost streaming solution to deliver what we expect to be hundreds of thousands of ‘keys’ purchased in these bundles.

VHX is pretty forward thinking on this front, again watching the games platforms carefully, and has come up with an elegant solution that works. We have been asking Humble to let us do a movies bundle for at least six months now, since we’ve had such success with them on the games side. They decided that this games+movies bundle would make for a stronger segue. They have delivered other types of media before such as music, soundtracks, audio books, and comedy records, none of which has had anywhere near the attach rate of their games bundles, but are still quite successful when compared to other digital options for those businesses. We expect films to do better than any of these other ancillary avenues they’ve tried.”

What is the split for all involved? There are several entities sharing in this Pay What You Want scenario, so is this mainly to bring awareness and publicity for all involved or is revenue typically significant?

MW: “In this particular bundle, since all the games and films are roughly $10 values, we’ve split it equally. So you have 10 artists splitting what will probably average out at $5 or $6 bucks a ‘bundle.’ But the volume will be so high, we still expect each of these filmmakers to make more money in these 10 days than they will likely make on their entire iTunes run.

And, TONS of new people watching their movies who would never have found it otherwise, which as a filmmaker, I know counts for as much as the money. I’d personally much rather have my film (and one of the films in the bundle is the last one I produced) in a bundle like this than shoveled onto subscription based VOD, and I know it’ll make more money and get more views.” [editor’s note: Those purchasing the bundle get to choose how the contribution is split between Devolver, Humble Bundle and the charitable contributions.]

Why did you decide to include a donation aspect to the Bundle? Is that an incentive to pay a higher price for the bundle?

MW: “Humble is committed to supporting charities with their platform. It’s part of the magic (other than the tremendous value) that makes their 4 million + regular customers feel really good about taking their chances on games (and other media) they’ve never heard of.

From Devolver’s standpoint, our last weekly games bundle on Humble resulted in nearly $150k for charity in addition to our developers all making a nice payday. It’s a miracle of a win-win-win. In this case, hopefully a lot of filmmakers will feel compelled to try this method out since it’s new, an incredible value, and will support TFC, who have helped so many filmmakers learn to navigate these murky waters. And there’s a very local, very specific cause on the games side, helping a champion of Indie Games like Brandon Boyer overcome his devastating personal situation of fighting cancer while battling mounting medical bills. It just feels good, and this is a big reason Devolver is such a fan of Humble Bundle.”

We can’t think of a better situation than contributing money to receive fantastic games and films while helping those who enable the creators to reach new audiences, keep rights control of their work and celebrate their creativity. Check out the Devolver Digital Double Debut on the Humble Bundle site. We thank Devolver, Humble Bundle and VHX for allowing us to partner with them on this initiative.

Sheri Candler March 7th, 2014

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution

Tags: Brandon Boyer, cancer, Devolver Digital, Devolver Digital Double Debut, documentary, Evil Geniuses, Good Game, Humble Bundle, independent film, Independent Games Festival, iTunes, Mike Wilson, non profit, Selling Your Film Without Selling Your Soul, Sheri Candler, The Film Collaborative, theatrical distribution, VHX, video games, VOD

Creating “live” films can be artistically and financially fulfilling

There is a lot of talk in independent film circles about the need to “eventize” the cinematic experience. The thought is that audiences are increasingly satisfied with viewing films and other video material on their private devices whenever their schedule permits and the need to leave the house to go to a separate place to watch is becoming an outdated notion, especially for younger audiences. But making your work an event that can only be experienced in a live setting is something few creators are exploring at the moment. Sure, some filmmakers and distributors are adding live Q&As with the director or cast, sometimes in person and sometimes via Skype; discussion panels with local organizations are often included with documentary screenings; and sometimes live musical performances are included featuring the musicians on the film’s soundtrack, but what about work that can ONLY be enjoyed as a live experience? Work that will never appear on DVD or digital outlets? Not only is there an artistic reason for creating such work, but there can be a business reason as well.

In reading a New York Times piece entitled “The one filmmaker who doesn’t want a distribution deal” about the Sundance premiere of Sam Green’s live documentary The Measure of All Things, I was curious to find out why a filmmaker would say he never plans for this work to show on streaming outlets like Netflix, only as a live event piece. I contacted Sam Green and he was kind enough to share his thoughts about why he likes creating for and participating with the audience of his work and why the economics of this form could be much more lucrative for documentary filmmakers.

The Measure of All Things is a live documentary experience to be screened with in-person narration and a live soundtrack provided by the chamber group yMusic. It is loosely inspired by the Guinness Book of Records and weaves together a series of portraits of record-holding people, places, and things, including the tallest man (7 feet 9 inches), the oldest living thing (a 5,000 year old Bristlecone Pine in Southern California), the man struck by lightning the most times (seven!), the oldest living person (116), and the woman with the world’s longest name, among others. This is the third such work Green has made to be viewed in this way; 2012’s The Love Song of R. Buckminster Fuller featured live music from Yo La Tengo and 2010’s Utopia in Four Movements with musical accompaniment by Dave Cerf were his previous works.

What draws you to your subjects?

SG: “I guess all of them have come out of curiosity. Ever since I was a kid I have been curious about things almost to the point of becoming obsessed. I am still the same, but now I’m making movies out of it. I obsessively research and look into things and sometimes that just goes nowhere, but occasionally it has turned into a movie and that is where they all have come from.

I don’t look at this in a strategic way. I don’t sit and think about what kind of project I could raise a lot of money for, or what would make a successful film. In some ways, I wish I did do that, but really I just make films that I would want to see.”

How do you tell if it will be a live performance piece or just a screen based piece? Does it have anything to do with being a performer?

SG: “I do both, but I am most inspired by the live stuff at the moment. For political and aesthetic and economic reasons, that form inspires me a lot these days so when I am making longer things, I work to make it a live cinematic event. I kind of backed into this form. It is an odd form. I’d never heard of people doing live documentaries. I stumbled into it and learned that I liked it, but it is a huge challenge for me. I am not a performer. Like most documentary filmmakers, I am a shy person and much more comfortable behind the camera. Part of why I like it is it is scary…scary as hell! But I’m learning a lot. I don’t want to keep making the same kind of movie over and over again.”

How do you usually collaborate with musicians for these works? How do you find them and what is the process of how you work?

SG: “To find people to work with, I just look at people whose work I love a lot. I have always been a big fan of Yo La Tengo, and I saw them do a night of music to a work by a French filmmaker called Jean Painlevé [Science is Fiction] and it was one of the best film viewing experiences I ever had. I was in the audience at one of the shows. I loved their sense of cinematic music so I asked if they would work with me on the Buckminster Fuller piece.

It is the same with yMusic, I saw them at Carnegie Hall and they have such a fantastic, huge, epic sound and I really wanted something like that for this piece. I got in touch and we worked something out.

The way I work with the musicians is like any film/music collaboration. A lot of back and forth, I shoot some video and they make some music and I adjust the video and write some voice over. It is just cobbling the whole thing together in an organic way.”

What are the challenges to taking your film on the road and performing night after night? It is like touring with a band.

SG: “The first live performance movie I made was Utopia in Four Movements. I was very pleasantly surprised how much we screened it. We screened it all over the world for several years after it was released. The challenge is you have to go to every screening and do the performance and it is a lot of work and time, but I actually love that. I am a filmmaker who likes to be around when the audience is watching and talking to them afterwards. Some filmmakers don’t, they want to go off and make another movie. But I like the distribution process, the challenge of distribution. I was never in a band as a teenager, so this is probably as close as I will get.

People often ask me at screenings, ‘Why not put this online and hundreds of thousands of people would see it? When you’re touring, maybe only a few thousand people will see it.’ And that’s true, but if you look at the most viewed clips on Youtube, most of them are super dumb. People view things online in a totally throw away manner. I am more interested in smaller numbers of people actually having a more meaningful experience through my work. It is a trade off I don’t mind, actually.”

Is it fair to say that these are more art pieces than films that have revenue potential?

SG: “No, and this is why I am happy to talk to you about the distribution part of my work. The film distribution business is in total flux. Everyone is trying to figure out how to survive, how to make money, in the new paradigm we are in. The truth is most people don’t. I know many documentary filmmakers whose films are out there, they have distribution deals, and they make no money whatsoever.

Although this was not my reason for creating my documentaries like this, I found that I make way more money on these live performances than I would make if these were traditional movies. The performance world still has an intact economy. If you go see a dance performance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music or the RedCat in LA, those performers get a performance fee that is pretty significant. They can get $10,000 to do a show. That is pretty standard performance fee.

The film distribution world has imploded largely because of the digital world. Everything is online, consumers are getting used to seeing things for free or very low cost. The bottom has really fallen out of the revenue. But that hasn’t happened to the performance world because there is no real digital equivalent to seeing a live performance. It is possible for a filmmaker to access this performance world. A lot of the shows I do are in the performance world; in museums and performing arts centers. The fees they pay are significant. I soon realized this is a much more viable way for me to distribute work.

I am guided by art and not primarily by financial considerations, but I also think filmmakers and artists should put their work out in a way in which they get something back from that. Artists should be compensated for their work and I am pained by the fact that many filmmakers make no money off of their films. Their films may get out there, but they don’t make any money from that. I am happy to have figured out a way to get my work out there and make money from it.

The film world is a few years behind the music world in terms of changes. The music world has already gone through all of this. Unless you are Miley Cyrus, you have to tour to make money as a musician. Not much is going to be made from downloads. I think the film world is also heading that direction and for me, this is a solution.”

How do your screening fees usually work? Is it a flat fee or a cut of revenue?

SG: “I screen these pieces in 3 different contexts. One is in the film context. I screen them at film festivals and we work out some screening fee amount. Festivals are strapped and so I negotiate on the fee.

The second is in a performance context. Say it is in a museum, they pay a flat fee and that has nothing to do with tickets sold. But I do work hard with the venue to sell tickets. I like to promote the screenings and I want them to do ok with the event.

The third way is in the context of the rock music world. The last piece I did was in collaboration with Yo La Tengo and we’ve done some rock concerts. When dealing with rock promoters, it is often pegged to how many tickets are sold. Those end up not being as good of a deal. Rock promoters are good at making money for themselves and their split is not very advantageous to the artist.”

Do you do these bookings yourself or through an agent?

SG: “I do book a lot myself. But I also work with Tommy Kriegsmann at ArKtype They book many performance people.”

Since a lot of your documentary performance depends on a written script, how is that different from making the traditional documentary with talking heads and maybe a little narration? Yours has a lot of narration.

SG: “The process is in a lot of ways still like making a film. You have an idea, you shoot a bunch of things, it turns out not to be quite what you thought, so you adjust and you start editing. I kind of edit and write voice over together. I’m a big fan of editing and doing many, many cuts to hone the piece. It is the same process one would do on an essay film.

But one thing about this form of film is you never really know what works until you show it to an audience. Only then can you tell whether people are engaged and when they’re not, you can feel it. So when you feel what works and what doesn’t, you can still make changes. We did our premiere for The Measure of All Things at Sundance a few weeks ago and now I have a million ideas of what I want to tweak. I think where I could change a line or put a pause and I can continue to work on it which is really fun and exciting. It allows me to really hone in on things in a way I couldn’t do with a normal film. You’re kind of done after you edit.”

Does that allow for you to change it from performance to performance for different audiences?

SG: “For the Buckminster Fuller piece, I did change things wherever we did it. Fuller did stuff everywhere so when we had some shows in London…he spoke there many, many times and he inspired some British architects so I worked all that into the piece. I can change it each time and that is part of the fun of it, it is a very fluid form.

The piece is in a Keynote file. I take still images and Quicktime video and put them in Keynote so I can go through and change things, swap out things. It is totally ephemeral.”

How do you fund your work? Do you get grants, investors, I saw that you recently did a campaign on Kickstarter?

SG: “It is a combination. Like any filmmaker, I am hustling. With this I got a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts. They have a multi-disciplinary grant and this project is a combination of film and performance. Some foundations have given me grants and some individuals and I did a Kickstarter campaign“

How was running that campaign? In one of your backer updates you said you weren’t sure about raising the money this way, which is a sentiment a lot of filmmakers who have been around for a while have expressed. How do you think it worked out and will you ever do that again?

SG: “That experience changed my feeling about Kickstarter and crowdfunding. I had been pretty grumpy about it because as a filmmaker I get TONS of campaign solicitations, you probably get them too. I felt bitter about that. Is this the level we’ve been reduced to as filmmakers, as artists? We are now funding our work by hitting up all of our friends? And the corollary to that is if I did give money to everyone who asks me, I’d be homeless. There was something that depressed me about the whole state of affairs.

One thing I had always heard people say, and I thought this was really just lip service, is there are a lot of people out there who want to be part of your work. For them, it isn’t a burden, they aren’t doing it out of charity or guilt or obligation. They are excited to be part of what you are doing. I had never taken that sentiment seriously. I always thought, ‘Wow I’m besieged by these campaigns and this sucks.’ But there are a lot of people who are not getting hit up by other filmmakers all the time and, for them, it is a way to help you get your work out into the world and be part of what you do.

I was struck during my campaign by the fact that this is TRUE. I was actually very moved by how many people responded and were so generous. It did change the way I think about it.

I would definitely do it again. I might do some things differently, like I wouldn’t do it when I was trying to finish the film. That was hard trying to finish the film and run a Kickstarter campaign at the same time. It just requires a lot of work.”

I noticed you have an ecommerce aspect to your website where you sell DVDs and streams for some of your other work. Do you purposely try to retain the right to distribute on your own?

SG: “Hell yeah, I’ve been doing that for a while. I’m not like a luddite. I love the internet and the way you can reach people all over the world. I made this movie about Esperanto called The Universal Language. There are people all over the world that still speak it. How would one reach people all over the world to see the movie? Without the internet and streaming, it would be impossible. I have a place on my site where people can pay $4.99 to watch it. That happens all the time and I think being able to use the internet to get work out there is fantastic.

Distribution is a trade off. With my film The Weather Underground, I had a terrific experience with distribution. The theatrical distributor was fantastic. The DVD people we worked with were great. I have nothing but good things to say about that. The truth is you give up money, but someone else is doing the work. So, in that sense, it can be a good deal.

But now, especially with people who want to distribute online, signing with a distributor who is going to tie up your rights, you often won’t make money from that. I am a big believer in either reserving some rights or making companies pay an advance if they are serious about distributing for you online. A lot of companies now are not paying anything up front and that means they don’t have an incentive to do a lot with the work.”

Green wanted to make it clear that he is not the only filmmaker creating live experience work. “I never want to give the impression that I am the only person out there doing this. There’s Brent Green, Jem Cohen, Travis Wilkerson. I was also very inspired by Guy Madden’s Brand upon the Brain. It had an orchestra and live foley and, when I saw it, Isabella Rossellini was narrating it and it was a such a great live cinematic event.”

Perhaps this has inspired some of you to rethink the cinematic form for your work. You have to be open to creating a live experience, putting yourself physically out there and screening in venues that are not specifically dedicated to filmed entertainment. But from an artistic and economic standpoint, these creations could be very fulfilling and lucrative.

The Measure of All Things is now booking screenings for 2014. Love Song for R. Buckminster Fuller is still on tour with upcoming screenings in Miami and Austin, TX. Sign up to Sam Green’s email list to stay updated on the screenings.

Sheri Candler February 12th, 2014

Posted In: Distribution, Film Festivals, Theatrical

Tags: ArKtype, Brand on the Brain, Brent Green, documentary, event cinema, film distribution, Guy Madden, independent film, Isabella Rossellini, Jean Painleve, Jem Cohen, Kickstarter, live documentary, National Endowment for the Arts, New York Times, R. Buckminster Fuller, Sam Green, Sundance Film Festival, The Measure of All Things, The Universal Language, The Weather Underground, theatrical distribution, Tommy Kriegsmann, Travis Wilkerson, Utopia in Four Movements, yMusic, Yo La Tengo

How did the Sundance 2012 narrative films fare?

The Sundance narrative films are always the hot properties going into the festival, but many of these star-studded films fade while starless films often surprise. Here’s a look at how the narrative films from the 2012 festival performed.

THE BIGGER PLAYERS

FOX SEARCHLIGHT

They acquired the audience and jury prize winners from the US Dramatic competition and both have scored Oscar nominations. The Sessions was acquired for worldwide rights for $6 million and with a $4 Million P&A (prints & advertising) minimum. It has grossed $5,818,544 in North America an additional $3,135,887 overseas. The film has since sold to dozens of territories. Beasts of the Southern Wild, meanwhile played in theaters for a whopping 20 weeks and despite never being in more than 318 theaters (60% of the max count for The Sessions at 516) grossed more than every Sundance film from 2012 except for one. Its gross stands at $11,539,605. Furthermore, it was bought at a bargain of under a $1,000,000. It has also been released in over a dozen countries that have reported box office grosses with many more sure to come in light of its best picture Oscar nominations insuring that the film will more than make back its $1.8 million dollar budget.

SONY PICTURE CLASSICS

SPC is really known as the best company for foreign films in the US and being the latest champion of Woody Allen, but they continue to be very prominent at Sundance. They snatched up two high profile narrative films that performed on extreme opposite ends of the spectrum.

Smashed was acquired for $1,000,000 on the strength of Mary Elizabeth Winstead’s performance. Unfortunately, it is not easy to market a serious movie about 20 somethings attempting to get sober. Despite decent if not great reviews, it will max out at under $400,000 gross even though it received the typical maximum playout that SPC has to offer with its run peaking at 50 screens. Once P&A are accounted for this film is pretty much a loss for SPC.

Celeste and Jesse Forever performed much better at the box office grossing $3,094,813, but it went as wide as 586 screens and only had 5 weekends where it averaged a PSA (per screen average) of over $1k. Acquired for $2,000,000, this film is most likely a slight loss for the distributor, but a big profit to the filmmaker who had a reported budget of under $900,000. It has grossed just over $200,000 from releases in 8 other countries.

OSCILLOSCOPE

28 Hotel Rooms barely played in more than 10 theaters and grossed $18,869. With so few locations, the focus was clearly on digital/VOD. For a NEXT film (meaning micro budget), it is far from a terrible gross and given poor to okay reviews. Hello I Must Be Going was an opening day film at the festival, but despite playing in more theaters during its run and not being available on VOD, it only managed $106,709. At its widest, it played in 15 theaters, but the expansion was too quick and the film fizzled fast.

IFC/IFC MIDNIGHT/SUNDANCE SELECTS

There are really two types of IFC releases in theaters. One is play a week at IFC Film Center in New York City and maybe one more location and the rest of the run is on VOD. The other is a theatrical push. In most cases, any late acquisitions announced well after a festival has wrapped fall into the former. Later acquisitions Price Check (2 theaters,$7,413 gross), Young and Wild (2 theaters, $5,514), and Save the Date (2 theaters, $5,719 gross) have all grossed less than $10k in one week of theatrical release. Also not passing that threshold are The Pact and Why Stop Now (3 theaters, $2,432 gross) . As a horror film, The Pact likely performed much better on VOD, covering its mid six figure acquisitions price. The other films were targeting minority communities (Young and Wild) or relying on stars (Save the Date and Why Stop Now ) to push ill-reviewed films. VOD was not reported, but most likely these other films were all acquired for under $100,000. They should all eventually prove profitable for IFC, but not the filmmakers.

In contrast Liberal Arts has grossed $327,345 which is more than Josh Radnor’s prior film Happythankyoumoreplease, but that film was dumped into the marketplace over a year after it won the audience award. Liberal Arts had the hot young actress Elizabeth Olson as a co star and produced a so-so gross for its over $1,000,000 acquisition price, meaning it had to do stellar on VOD, foreign and other ancillaries to be profitable

Sleepwalk With Me meanwhile relied on a built in audience to get the message across and is truly something unique that is not easily duplicated by other indie films. It had the boost of winning Best of NEXT Audience Award at Sundance, a prime follow up at SXSW, Birbiglia’s comedian following and with, Ira Glass as producer, a tie in to “This American Life” which has a very loyal following. The film grossed $2,266,067 on 135 screens at its peak, stayed in theaters for 3 months and was followed very closely by a cable VOD release.

This has not been a particularly strong year for IFC, but Sleepwalk With Me is its highest grossing film theatrically and the filmmakers themselves heavily promoted the film instead of relying on higher cost promotional/marketing methods as the central way of getting out the word. All parties worked overtime to push the film and it is not a model that an unknown would be able to ever duplicate.

MAGNOLIA/MAGNET

Magnolia admitted that part of the reason it was not financing the awards campaign for Ann Dowd for Compliance was because the film lost money. While this controversial film is the third highest grossing film ever from the Next section and $319,285 is nothing to cry about, the film was also not released day and date VOD as is typical for the distributor. In its first week it amassed $43,346 on one screen, but it did not hold up well in expansion. It topped out at 21 screens in its fourth week and while the acquisition price wasn’t reported, it most likely was no more than low six figures. I think this is a case of unrealistic expectations.

V/H/S played in almost as many theaters and only grossed $100,345 (releasing in October, naturally), but as with The Pact its money came from VOD and a sequel (S-V/H/S) was quickly put through which was at this year’s fest (picked up for release by IFC). Even though $1,000,000 was spent to acquire it, this film should prove to be pretty profitable.

Meanwhile, Nobody Walks was only in theaters for 5 weeks and never played on more than 7 screens, grossing a measly $25,342 . It was acquired for mid-high six figures and the focus was clearly always on VOD. While VOD was not reported, given the cast and producing powers it is likely to have recouped.

Magnolia also released 2 Days in New York, the sequel to 2 Days in Paris to the tune of $633,210 and Magnet came to the festival with Tim and Eric’s Billion Dollar Movie which did okay theatrically with $201,406.00 and both likely had a robust life in the digital sphere.

TRIBECA FILM

Tribeca Film released two US Dramatic entries. For Ellen grossed $12,396 on 3 screens for 7 weeks despite the presence of Paul Dano. The Comedy however has grossed $41,113 on 4 screens for 8 weeks and the bulk of that coming from one screen in NY capitalizing on its Brooklyn setting. Both did day and date, but I imagine The Comedy outperformed For Ellen there too.

THE ONE OFFS

Keep the Lights On and Middle of Nowhere did almost identical business. Middle of Nowhere was released by writer/director Ava DuVernay’s distribution company AFFRM and played in a mix of major urban megaplexes and arthouse theaters, grossing $236,806 on 25 screens for a total of 9 weeks in theatrical release. Keep the Lights On had the backing of Music Box Films and relied heavily on screens from Landmark and specialty houses in LGBT dominant markets. The film grossed $246,112 on 10 screens for a total of 16 weeks in theatrical release. Red Hook Summer hired Variance Films for its DIY theatrical and grossed $338,803 on 41 screens for total of 11 weeks in theatrical release. The Spike Lee feature was made for under $1,000,000. While it grossed more than the two films above, it did so with a brand name director.

Safety Not Guaranteed was acquired by Film District for over $1,000,000 and grossed $4,010,957 on 149 screens for a total of 19 weeks in theatrical release. The film only cost $750,000 to make and has had some international success too.

Focus Features paid over $2,000,000 for worldwide rights to For a Good Time Call but the film only grossed $1,251,749 in the US and a little over $100,000 in the UK. This may seem bad, but the film was available on VOD when it opened and has been a top performer on iTunes. It never played in more than 107 theaters. The film cost $1,300,000 to make so it also turned a nice profit for the producers.

The $2.5 Million budgeted Robot and Frank was acquired by Sony and Samuel Goldwyn for over $2 Million and grossed over $3.3 Million theatrically. It has grossed another almost $500,000 internationally.

But the big success is Roadside Attraction’s Arbitrage which they paid over $3,000,000 for and chose to do VOD/Theatrical. It has grossed almost $8,000,000 and equaled that on VOD.

Lastly, The Words was the only Sundance 2012 film to get a wide release, 2801 screens. CBS bought the closing night film for $2,000,000. It managed $11,494,838 barely out performing Beasts of the Southern Wild.

THE BIT PLAYERS

Image debuted the star studded film Goats on four screens to a PSA of under $500 and its theatrical run quickly ended in one week. The film was acquired for almost $1,000,000 coming nowhere close to the film’s $5,000,000 Budget. A loss for all involved.

California Solo is still in theaters, but with a current gross of $15,433 on 2 screens for the last 6 weeks, it is not a breakout for Strand Releasing. Unlike a lot of recent Strand acquisitions from Sundance, it actually received a theatrical release.

Teddy Bear is one of the few world dramatic films to sell and though it only grossed $16,138 for Film Movement, this is a notable success. It is a foreign mumblecore film with no name actors and it out grossed other films that have been released from the same programming section.

Sony Worldwide’s release of The First Time will likely be its last since the film couldn’t get over $25k despite opening in 19 theaters. The theatrical only lasted one week.

Madrid, 1987 and That’s What She Said did not report grosses. The latter shared screens in LA and NY then immediately went digital courtesy of Phase 4. The Film Collaborative handled the theatrical for Mosquita Y Mari. While it grossed under $15k, it is the highest grossing Lesbian narrative of 2012 that received theatrical release.

THE VOD OVERPAY

TWC Radius release Lay the Favorite is a domestic theatrical flop and not likely to justify the acquisition price of over $2,000,000. Lay the Favorite grossed only $20,998 theatrically in the US and has barely grossed over $1,000,000 abroad. Considering the production cost was $20,000,000, there are probably a lot of angry investors.

Their second acquisition, Bachelorette, cost a fraction of that production budget at $3,000,000 and has grossed almost $10,000,000 overseas ($447,954 domestically) and debuted at #1 on iTunes. The advance cost was $2,000,000. It will recoup for investors and may ultimately do so for TWC thanks to the likes of Rebel Wilson.

Millennium meanwhile is probably questioning paying just under $4,000,000 for Red Lights which grossed a puny $ 52,624 at the box office. With the star power and being a genre film, it is likely to have performed much better on other outlets, though the path to profit would be daunting at that acquisition price. It has made over $13,000,000 overseas theatrically. Despite that, it is possible it won’t make back it $17-20 Million production budget.

RECAP

- While VOD adds costs to a theatrical, it is often a win-win for distributors and filmmakers.

- NEXT films are doing better at the box office, but still not measuring up to the box office of the US Dramatic films.

- 9 of the 38 Narrative releases grossed over $1,000,000 (5 premiere, 3 US Dramatic, 1 Next)

- 8 of the 38 narrative releases failed to gross over $10k at the box office (3 Premiere, 2 World Dramatic, 1 US Dramatic, 1 Next, 1 Midnight)

BLOG EXTRA

Sundance received over 12,000 submissions for under 200 slots at the 2013 festival. You are more likely to get into Harvard than you are into Sundance. Yet a number of people manage to do it multiple times and even in the same year. Here are the double and triple players.

David Lowery co-wrote and co-produced Pit Stop and also wrote/directed Ain’t Them Bodies Saints and edited Upstream Color. All were official selections at Sundance this year.

James Franco and Vince Jolivette each have Interior. Leather Bar, Lovelace, and Kink. Jolivette is a producer on all three films. Franco co-wrote and stars in Interior. Leather bar, stars in Lovelace and directed Kink.

Mary Elizabeth Winstead stars A.C.O.D and The Spectacular Now. Her costar in The Spectacular Now, Brie Larson, is also in Don Jon’s Addiction.

Juno Temple is in Afternoon Delight and Lovelace.

Casey Wilson co-wrote and stars in Ass Backwards and is also in C.O.G

Amy Seimetz is not only one of the stars of Pit Stop, but this indie darling is also in Upstream Color.

Table for your reference of the docs and narratives from Sundance 2012

| Film | Company | Deal Amount | Terrtitories | Sales Company | Box Office/Release | Section | Budget | Other Theatrical Countries with reported grosses | Additional Countries with a release | International Grosses |

| Bestiaire | Kimstim Films | US | $1,428.00 | New Fron | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Putin’s Kiss | Kino Lorber | N/A | North America | N/A | $9,114.00 | world doc | NA | Denmark | NA | |

| The Law in These Parts | Cinema Guild | US | Liran Atzmor, Produce | $10,309.00 | World Doc | NA | NA | NA | ||

| China Heavyweight | Zeitgeist | N/A | US | EyeSteelFilms | $10,550.00 | World Doc | NA | Japan | NA | |

| Payback | Zeitgeist | N/A | US | N/A | $17,979.00 | World Doc | NA | Canada | NA | |

| The Ambassador | Drafthouse Films | N/A | US | Trustnordisk | $28,102.00 | World Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| West of Memphis | SPC | N/A | Worldwide | Peter Jackson and Ken Kamins | $46,307 | Doc Premiere | NA | Portugal, United Kingdom | NA | |

| The Invisble War | Cinedigm and New Video | N/A | North America | The Film Collaborative | $62,649.00 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| 5 Broken Cameras | Kino Lorber | N/A | US | CAT&Docs | $74,571.00 | World Doc | $250,000 | United Kingdom | Canada, Japan, Sweden | $36,372.00 |

| Escape Fire | Roadside | N/A | US | CAA | $87,577 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| Marina Abramovic | Music Box | N/A | US | Submarine | $86,637.00 | us doc | Austria, Italy, Poland, Russa, Ukraine | France, Germany, Ireland, United Kingdom | $57,127.00 | |

| How To Survive a Plague | Sundance Selects | High Six Figures | North America | Submarine | $123,814.00 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| The Other Dream Team | Film Arcade & Lionsgate | Mid Six Figures | North America | WME | $135,228.00 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| The House I Live In | Abramorama | US Theatrical | $186,059 | US Doc | United Kingdom | $8,407.00 | ||||

| Something From Nothing: The Art of Rap | Indomina | Over $1,000,000 | Worldwide | UTA | $288,312.00 | doc premiere | United Kingdom | NA | $45,388.00 | |

| Detropia | DIY | $377,219 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| Ai Weiwei: Never Sorry | Sundance Selects | N/A | North America | Cinetic Media, Victoria Cook | $489,074.00 | US Doc | Austria, Germany, Russia, United Kingdom | Denmark, Sweden, Taiwan | $334,911.00 | |

| Shut Up and Play the Hits | Oscilloscope | N/A | North America | WME | $510,334.00 | Midnight | United Kingdom | Germany, Portugal | $118,773.00 | |

| Chasing Ice | Oscilloscope | N/A | US (Non TV) | Submarine | $940,300 | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| The Imposter | Indomina | N/A | North America | A&E Films | $898,317.00 | World Doc | Denmark, Russia, United Kingdom | Australia, France, Ireland, Kuwait, Netherlands, New Zealand, Sweden | $1,870,940.00 | |

| The Queen of Versailles | Magnolia | Mid Six Figures | North America | Submarine | $2,401,999.00 | US DOC | United Kingdom | NA | $93,707.00 | |

| Searching for Sugar Man | SPC | Mid Six Figures | North America | Submarine | $3,095,075 | World Doc | Australia, Denmark, New Zealand, Sweden, United Kingdom, United Arab Emirates | France, Germany, Netherland, Norway | $2,203,958.00 | |

| Indie Game: The Movie | HBO And Scott Rudin (Remake Rights) |

N/A | TV | Film Sales Company | B.O. Gross not Reported |

world doc | NA | Taiwan | NA | |

| Big Boys Gone Bananas | DIY Theatrical | US | B.O. Gross Not Reported | World Doc | NA | Sweden, Canada, UK | NA | |||

| Bones Brigade | The Film Sales Company/Sundance Artist Services | DIY Theatrical and Digital Platforms | US | The Film Sales Company | B.O. Gross Not Repoted | Doc Premiere | NA | Japan | NA | |

| Room 237 | IFC Midnight | N/A | North America | Betsy Rodgers | 2013 | New Fron | NA | Denmark, Ireland, Sweden, United Kingdom | NA | |

| Under African Skies | Snag Films | N/A | Exclusive Digital | A&E Films | Digital | Doc Premiere | NA | NA | NA | |

| The House I Live In | Snag Films | Domestic Distribution | Digital | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |||

| Love Free or Die | Wolfe | US DVD/VOD | Cinephil | Digital | US DOC The film will be available for educational/non-theatrical screenings beginning in October through Kino/Lorber in partnership with Wolfe, followed by airings on PBS stations nationwide as part of the series “Independent Lens.” Wolfe will release the film on DVD/VOD in 2013. | NA | NA | NA | ||

| About Face | HBO Doc | N/A | TV | Pre-Fest | TV | Doc Premiere | $500,000 | NA | Italy | NA |

| The D Word | HBO Doc | N/A | TV | Pre-Fest | TV | doc premiere | NA | NA | NA | |

| Chasing Ice | National Geographic | N/A | TV | Submarine | TV | US Doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| Marina Abramovic | HBO Doc | TV | Pre-Fest | TV | us doc | NA | NA | NA | ||

| Me @ The Zoo | HBO Doc | Mid Six Figures | TV | Submarine | TV | us doc | NA | NA | NA | |

| The Queen of Versailles | Bravo | N/A | TV | Submarine | TV | US DOC | NA | NA | NA | |

| Ethel | HBO Doc | N/A | TV | Pre-Fest | TV/B.O. Gross not reported | Doc Prem | NA | NA | NA | |

| Under African Skies | A&E Films | N/A | TV/Theatrical | A&E Films | TV/B.O. Gross Not Reported | Doc Premiere | NA | NA | NA | |

| A Place At the Table (Finding North) | Magnolia | US | Submarine | US DOC | NA | NA | NA |

Bryan Glick January 29th, 2013

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Theatrical

Tags: film festival, independent film, Sundance 2012, theatrical distribution, theatrical release

The Independent’s Guide to Film Exhibition and Delivery 2013

2012 was a profound and often painful year in terms of the rapid technological change impacting the delivery and exhibition of independent film.

2012 was the year we wrapped our heads around the idea that there are virtually no more 35mm projectors in theatrical multiplexes, and that the Digital Cinema Package (DCP) has taken its throne as king – right alongside its wicked little stepchild, the BluRay.

2012 was the year it became clear that the delivery and exhibition formats we’ve been relying on for the last few years (especially HDCAMs) are no longer sufficient, and that in order to keep pace with the marketplace, we must now embrace the next round of digital evolution.

There are many filmmakers who will now want to stop reading, thinking “ughh, techie-nerd speak, that’s for my editor and post-supervisor to worry about.” You may believe you are first and foremost an artist and a storyteller, but in today’s world your paintbrushes are digital capturing devices, and your canvas is the wide array of digital delivery systems available to you. To shield yourself from the reality of how technological change will affect your final product is to face sobering and expensive complications later that will dramatically impact your ability to exhibit your film in today’s venues (including film festivals, theatres, and other public screening venues), as well as meet the needs of distributors and platforms worldwide.

And, so, for this New Year, I offer this “Guide to Exhibition & Delivery 2013,” a quasi-techie survival guide to the landscape of technological change in the foreseeable future, keeping in mind that this may all look very different again when we revisit this just a year from now…

What changed in 2012?

As 2012 began, major film festivals worldwide had largely coalesced around the HDCAM (despite slight but annoying differences in North American and European frame rates); and distributors and direct-to-consumer platforms were largely satisfied with HDCAM or Quicktime file-format deliveries, although varying platforms required different file specifications which could prove difficult for independent filmmakers to match (most notably iTunes). In addition, a large sector of the distribution landscape, including small film festivals, educational institutions (universities, museums, etc), and even small art house theaters remained content to screen on DVD and other standard-definition formats. The high-definition BluRay – with its beautiful image quality and powerful economic edge in terms of cost of production, shipping, and deck rental — was also emerging as an alternative to HDCAM, Digibeta, and DVD exhibition, despite the warnings by the techie/quality-control class that BluRays would be perilously unreliable in a live exhibition context.

But behind the scenes, the engine of the corporate machine driving studio film distribution was already fast at work driving top-down change. Finally, after years of financial impasse as to how to equip the theatrical network with digital projectors, the multinational Sony / Technicolor / Christie Digital / Cinedigms of the world had immersed themselves fully in the space and converted the North American multiplex system to a digital, file-based projection standard set by DCI LLC (a consortium of the major studios) – saving the studios immeasurably in print and shipping costs, as well as standardizing and upgrading image quality and providing additional security against piracy. This standardization as defined by the DCI studio consortium had already been growing in Europe for years before the North American market caught up, and became known worldwide as the DCP (Digital Cinema Package).

Once the largest technological and exhibition purveyors worldwide had made their move towards standardizing film exhibition, the writing was already on the wall, although it would take several more months to make its impact fully felt in the independent world.

What is a DCP?

A Digital Cinema Package (DCP) is a collection of digital files used to store and convey digital cinema audio, image, and data streams. General practice adopts a file structure that is organized into a number of Material eXchange Format (MXF) files, which are separately used to store audio and video streams, and auxiliary index files in XML format. The MXF files contain streams that are compressed, encoded, and (usually) encrypted, in order to reduce the huge amount of required storage and to protect from unauthorized use (if desired). The image part is JPEG 2000 compressed, whereas the audio part is linear PCM. The (optional) adopted encryption standard is AES 128 bit in CBC mode.

The most common DCP delivery method uses a specialty hard disk (most commonly the CRU DX115) designed specifically for digital cinema servers to ingest the files. These hard drives were originally designed for military use but have since been adopted by digital cinema for their hard wearing and reliable characteristics. The hard drives are usually formatted in the Linux EXT2 or EXT3 format as D-Cinema servers are typically Linux based and are required to have read support for these file systems.

Hard drive units are normally hired from a digital cinema encoding company, sometimes (in the case of studios pictures) in quantities of thousands. The drives are delivered via express courier to the exhibition site. Other, less common, methods adopt a full digital delivery, using either dedicated satellite links or high speed Internet connections.

In order to protect against the piracy fears that often surround digital distribution, DCP typically apply AES encryption to all MXF files. The encryption keys are generated and transmitted via a KDM (Key Delivery Message) to the projection site. KDMs are XML files containing encryption keys that can be used only by the destination device. A KDM is associated to each playlist and defines the start and stop times of validity for the projection of that particular feature.

As a result of all the standardized formatting and encryption features, the DCP offers a quality product generally considered to be superior to 35mm (while simultaneously conforming to the beloved 24 fps rate of 35mm), and a product that can theoretically be shared around the world with less variables and greater reliability than most formats (since 35mm) to date. Given the confusing array of formats facing filmmakers in recent years, there are many ways that the DCP revolution seems a singular advancement worth applauding, and at least on the surface, as a clear way forward for film exhibition and delivery for years to come.

So what’s wrong with that?… DCP survival for independents.

Before running out to master your film on DCP now, it is important to consider at least the following mitigating factors, 1) the utility of the format, 2) the price of DCP (including the hidden costs), and 3) the newness of the format and the inherent dangers associated with new formats, and 4) the ways that DCP will not save you from the usual headaches of delivery, and is in many ways an existential threat to independent film distribution as we currently know it.

With regards to the utility of DCP, remember that it is currently a cinema exhibition product, not a format that will be useful for delivery to distributors, consumer-facing platforms, DVD replicators etc. So, obviously you must be quite sure that you have actually made a theatrical film, and by this I mean theatrical in the broadest sense possible…i.e. will your film actually find life in cinematic venues including top film festivals etc. Following the industry at large, film festivals around the globe are in hyper-drive to convert to DCP as their preferred or even exclusive format. Going into the film festival circuit in 2013 and forward in any mainstream/meaningful way without a DCP…especially for narrative features….will be challenging to say the least (although likely still doable if you are willing to forfeit some bookings and some quality controls). But if you aren’t sure yet if your film will actually command significant public exhibition at major festivals and theatrical venues, you probably shouldn’t dive into the pool just yet.

Not surprisingly, the largest concern to independents is the issue of price. While nowhere near to the old cost of 35mm, DCP does represent a significant increase in mastering cost over HDCAM, Digibeta etc. In researching this article, most labs quoted me a rate of approx. $2,000 for a ninety minute feature, plus additional costs for the specialty hard drives and cables etc. that put the total closer to $2,500 +. As is the case with most digital products, however, it appears the costs are already headed downward as more and more independent labs get into the space, and it seems reasonable to assume that the price-conscious shopper should be able to find $1,500 and even $1,000 DCPs in the near future (especially with in-house lab deals working for specific distribution companies).

Following the initial mastering costs, the files can be replicated onto additional custom hard drives for prices in the range of $300 – $400, which is at least relatively commensurate with HDCAM replication. This replication process is controversial however — there is no doubt that one can decide to skirt this cost by transferring the files to standard over-the-counter hard drives that run in the range of $100 (we have already distributed one film theatrically and successfully using standard, low-price hard drives). But many labs and exhibitors will warn you against this, telling you that using non-custom hard drives and cables increase the chance that the server at the venue will not be able read the files, and therefore unable to ingest and project the film when it counts most.

In fact, to avoid these potential compatibility issues with differing hard drives, cables etc, some exhibitors (most notably Landmark) are requiring distributors and filmmakers to use specific labs who encode all their content, which perilously puts the modes of production in the hands of the few, and may ultimately keep the cost artificially high. And while indeed there are many reasons to fear compatibility issues between DCP and server (I have already heard of/attended numerous screenings cancelled or delayed in 2012 due to DCP compatibility issues), it is in fact this level of lab and exhibitor control over the product that makes me very nervous about the future of DCP in the independent distribution space.