Casting Your Independent Film

TFC commissioned this guest blog post by casting director Matthew Lessall, CSA because casting decisions have a big influence on distribution… and that we have never covered the subject before…

Matthew Lessall, CSA is a freelance casting director with credits that include the 2015 Cannes award winning film for best screenplay, “Chronic” (starring Time Roth) and the 2016 film “Miss Stevens” (starring SXSW best actress winner, Lily Rabe). Matthew is Co-President of the Casting Society of America. He is in the final stages of his “how-to guide”: “HOW TO CAST LOW BUDGET INDEPENDENT FILM – A guide for first time producers, directors and film makers.”

THE CASTING PROCESS

I think what is so unique about what I do, is that every film is different. The bones of what I do, how I do it, the pace, timing, knowledge, it is all part of the experiences I have had on previous work – but every job is different with different circumstances. Saying all of that, there are basic “actions” to tackle when casting.

Being ready to start can mean so many different things, but for the sake of pairing down what I do to basics, let’s assume that a film has a producer, line producer, attorney and director attached. Financing is in place (or at least some of it) and its now time to talk about casting. This is when I come on board.

The most important thing in my mind is that I have a firm grasp on story, characters, plot, tone and a mutual understanding about the direction the film makers want to take the film in. My number one casting philosophy is, “Everyone must be in the same film.” Meaning that all of the actors cast must feel like they are part of this universe being created. But possibly more importantly is that the crew needs to be on the same page. If the producer and director are not communicating well, if the costume designer or set designer, lighting, if everyone is not “on point” then you are going to have troubles.

From the start, what I do is flesh out who could be in the roles of the film. I create lists. I sit down and spend hours on each role trying to think about actors, the obvious ones who are box office draws, to the ones I have seen in theatre or film festivals, or met on a general a year or often years before. What I do is what I like to call, “casting director stalking,” following the careers (or the lack there of – because sometimes that’s where the gems are found) and cobble together the potential of what could make a great cast. This all takes time, because anyone can go on IMDBPro and make a list of actors, but a talented casting director gets into the mind of the writer, thinks about what an actor whom nobody else is thinking of could bring to a film and fights for those actors to illuminate the story in ways not thought of before. This concept may seem to contradict the, “everyone must be in the same film” philosophy, but if done correctly (it’s an art by the way—watch the HBO doc ‘Casting By’ and you will see what I mean) the casting process should elevate the script, enlighten the story, enhance the possibilities, and illuminate where there was no shine.

You have to remember we are talking about actors. Actors, the best ones, are artists, they are practicing a craft. When you watch great acting, you should feel transported. Your very state of being should be “out of body” you should not feel like you are watching, you should just be feeling. I know it sounds hippy-dippy, but that’s what I think I try to bring (under the best circumstances) to the job. I don’t hit it out of the park every time, it doesn’t always happen, but it was I strive to do – when I am given the freedom to do so.

Now that you have my philosophy, the basics are, I read the script, write a breakdown of all of the roles, write my own version of a synopses and log line (see if it matches what the writer has written) and then I consult with the director and producer. I bring the lists, I show my ideas, I send links of actors. I send the breakdown out to agents. I call the agents who I work with, I get the film covered by the agents. I think about who at every top agency has someone who may be right for the film. I discuss the budget with the agents so they know what the deals would look like. In general, I would say any film under $5 million dollars, the representatives have a good idea of what the standard fees and offers are going to look like. I then talk to my team and we start to figure out who we would make a direct offer to, who they would want to meet and I start auditions to introduce the director to actors and to give actors who want the chance to be seen (whom I think could be right for the role), a shot in front of the director.

Auditions are where a lot of creative work is done. It is often the first time the director has heard the words spoken out loud. It gives me a chance to see how the actors are responding to the script and to the director. And it shows me how the director communicates with the actors. I could write more on this topic, because this is a big deal: how the Director communicates – it can sometimes sabotage the casting process. But assuming everything is running smoothly, auditions are also where the characters as written can change from male to female, Caucasian to Latino, where can we see different types of actors who truly populate the world we are creating and/or reflect the world we live in.

I call the agents, set up the offers and deal points and confirm everything in writing, copy the production attorney and wait for an actor to accept the role. Once that happens, there is additional negotiation and additional deal points that need to be hammered out. Depending on various situations, I will do this work or the production attorney will take on closing the deal.

In general, anyone that is considered a scale player with no back-end or a day player, I will close that deal. Once a deal is closed, all of the paperwork is sent to production and they handle travel, housing, call times, etc…

ATTRACTING “NAME” TELENT AND HOW THIS EFFECTS DISTRIBUTION (AND CASTING GODS)

Many times I am asked to try to get a name actor into a film. This mostly has to do with the foreign distributors, because they feel more comfortable selling a film that has someone in it that they recognize. Every distributor is different, they all have different ideas and lists of who means something for their specific territory. In general, my rule is, if my Mother knows who the actor is then the distributor will be happy. It’s that simple and that lame all at the same time.

One thing I have seen time after time is that the more known names you have in your film the better chance you will have with distribution—this is true. This does not always correlate to creating a beautiful film. My second philosophy on casting is this: “Cast the best actor for the role.” You will always be happier doing this, it may mean more work from your producer or sales team to get the film in front of a distributor, but the film will be better for it and at the end of the day, that is what you want right? Not to sell out your integrity as a film maker? But so many do sell out—please travel to AFM, EMF or the Marche—where you will see film titles that make you wonder, “how is that film watchable?”

If you don’t have a ton of money to spend on an actor, then you better have a combination of the following to attract A-list talent: A director with an excellent festival history or some cool quotient like directing A-list music artists in music videos, or winning an Academy Award for a short film, or a writer/director with a script that wins a prestigious awards, like the Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting. A producer who has a great track record. An attorney who has worked on award winning low budget independent film. You should be able to show how amazing your cinematographer is. The vision of the film should be clear and presented in a look-book, on a website, with examples of how the film is to look. Any crew members with distinguished credits on their resume should be highlighted and touted. If you have an actor attached, who is that actor? Is your director or writer or producer represented by a major agency or manager – this can help a lot.

Try to remember that your film is not the only film that is being cast. You are competing with hundreds of films, television shows, theatre – all of them are trying to get the same 10 actors into their shows and getting an actor to read your script even with an offer (let alone getting the agent to read it) takes time. And if the casting situation is time sensitive, then you must have some combination of the above…or faith in your Casting Director to make a miracle happen.

As an example, last year, I cast a film called A POSTHUMOUS WOMAN. It was shot in Northern California and the budget for the film was under an Ultra-Low Agreement. I loved the script, and we had a well known, successful independent producer with known festival award winning credits to back up the film with a co-director/writing team that had never directed a feature film before. But the script was great, and Lena Olin’s manager liked it, so we made an offer to Lena Olin for the lead role. It took six months from the moment I offered her the role to the time she accepted the role. The only reason she even read the script is that her husband picked it up and read it randomly and told her that this was a role she had to play. I had faith that this material was going to connect with Lena Olin – I just prayed to the Casting Gods to make a miracle happen. And by the way, these are the only Gods I believe in, because let me tell you, they have come through multiple times in my career!

#iknowisoundcrazy – but it’s the truth.

There is a deep faith your casting director must have in the material in order to punch through getting A-list talent onto a low budget film. There is strategic consideration, strategic phone calls, placement of how to pitch the team, I try to make the film the coolest project ever – things like that that go into getting that talent to say yes and into getting the best cast possible.

SOME CASTING DOS & DON’TS

Do research who you want to cast your film. Look at films that you love, films that you think are similar to the one you are making and find out who cast that film. Reach out to that casting director and see if there is interest from them to cast the film. Just like actors, some casting directors will meet with you without an offer, some won’t.

Do trust your casting director: they are usually the ones who won’t bullshit you or sugar coat things. They are the ones who want this cast well too – it’s their name in the main titles – so it is in their best interest to make the best film possible.

Do have a strong opinion about actors. Know actors! If you don’t know actors, don’t poo-poo suggestions because they are not “The Ryans” (Gosling, Reynolds, Phillippe). If Joseph Gordon-Levitt or Rachel McAdams are on your list, you should probably have a back-up.

Do have a strong vision for your film. Answers like “yes” and “no” help us a lot. Casting Directors can work with “yes” and “no”, wishy-washy, not specific answers are not good. My high school acting teacher said it best, “God is in the details!”

Don’t show up late to auditions.

Don’t text during auditions. Pay attention to the actors!

Don’t ever ask how old an actor is while in the audition. You will be breaking State and Federal employment laws. Anything that you need that is personal background information on actors can be found out after the audition via the Casting Director speaking with the actor’s rep. And if you want to get to know an actor more, take them out to coffee after the audition to find out if this is the person you want to spend the next 3,4,5,6 weeks with.

IN CONCLUSION

Casting is about taste. It’s about knowing actors. It’s about connecting the written word to the spoken word by having a deep and meaningful understanding of the acting process and actors. Casting is about relationships. The relationships built with actors, agents, managers, producers, directors, etc… Casting well is about trusting in the process. Successful casting is not done in a vacuum. It takes a leader, a strong director with a vision, a producer who can execute that vision and great communication between all. Most of all, it should be the most rewarding part of the film making process.

Orly Ravid April 9th, 2016

Posted In: Uncategorized

Get Educated About Educational Distribution:

Part 1 of a 3-part Series

by Orly Ravid, Founder, The Film Collaborative

Orly Ravid is an entertainment attorney at Mitchell Silberberg & Knupp (MSK) and the founder of The Film Collaborative with 15-years of film industry experience in acquisitions, festival programming, sales, distribution/business affairs, and blogging and advising. She also contributed to the Sundance Artist Services initiative.

Filmmakers usually think selling their film to distributors means that they will handle the whole release including theatrical, home video, and of course now digital/VOD. One category of distribution that is often overlooked, or not fully understood, however, is educational distribution. It can be a critical class of distribution for certain films, both in terms of reaching wider audiences and making additional revenue. For a certain type of film, educational distribution can be the biggest source of distribution revenue.

What is it?

When a film screens in a classroom, for campus instruction, or for any educational purpose in schools (K-university), for organizations (civic, religious, etc.), at museums or science centers or other institutions which are usually non-profits but they can be corporations too.

This is different from streaming a film via Netflix or Amazon or renting or buying a commercial DVD. Any film used for classes / campus instruction / educational purposes is a part of educational distribution and must be licensed legally. Simply exhibiting an entire film off of a consumer DVD or streaming it all from a Netflix or Amazon account to a class or group is not lawful without the licensor’s permission unless it meets certain criteria under the Copyright Act.

Initially, this was done via 16mm films, then various forms of video, and now streaming. These days, it can be selling the DVD (physical copy) to the institution/organization to keep in its library/collection, selling the streaming in perpetuity, renting out the film via DVD or streaming for a one-time screening, or exposing the content to view and at some point (certain number of views) it is deemed purchased (a/k/a the “Patron Acquisition Model”).

What type of films do well on the educational market?

In general, best selling films for educational distribution cover topics most relevant to contemporary campus life or evergreen issues such as: multiculturalism, black history, Hispanic studies, race issues, LGBTQ, World War II, women’s studies, sexual assault, and gun violence; in general films that cover social and political issues (international and national); health and disability (e.g. autism); and cinema and the arts. A great title with strong community appeal and solid perception of need in the academic community will do best (and the academic needs are different from typical consumer/commercial tastes).

At The Film Collaborative, we often notice that the films that do the best in this space sometimes do less well via commercial DVD and VOD. This is true of films with a more historic and academic and less commercial bent. Of course, sometimes films break out and do great across the board. Overall, the more exposure via film festivals, theatrical, and/or social media, the better potential for educational bookings though a film speaking directly to particular issues may also do very well in fulfilling academic needs.

Sourcing content

Across the board the companies doing educational distribution get their content from film festivals but also simply direct from the producers. Passion River and Kanopy, for example, note that film festival exhibition, awards, and theatrical help raise awareness of the film so films doing well on that front will generally perform better and faster but that does not mean that films that do not have a good festival run won’t perform well over time. Services such as Kanopy, Alexander Press, and Films Media Group collect libraries and get their films from all rights distributors and those with more of an educational distribution focus as well as direct from producers. These services have created their own platforms allowing librarians etc. to access content directly.

Windowing & Revenue

There are about 4,000 colleges in the US and about 132,000 schools, just to give you a sense of the breadth of outlets but one is also competing with huge libraries of films. Educational distributors such as ro*co films has a database of 30,000 buyers that have acquired at least one film and ro*co reached beyond its 30,000 base for organizations, institutions, and professors that might be aligned with a film. All rights distributors often take these rights and handle them either directly, through certain educational distribution services such as Alexander Press (publisher and distributor of multimedia content to the libraries worldwide), Films Media Group / Info Base (academic streaming service), or Kanopy (a global on-demand streaming video service for educational institutions), or a combination of both. There are also companies that focus on and are particularly known for educational distribution (even if they in some cases also handle other distribution) such as: Bullfrog Films (with focus on environmental), California Newsreel (African American / Social Justice), Frameline Distribution (LGBTQ), New Day Films (a filmmaker collective), Passion River (range of independent film/documentaries and it also handles consumer VOD and some DVD), roc*co films (educational distributor of several Sundance / high profile documentaries), Third World Newsreel (people of color / social justice), Women Make Movies (cinema by and about women and also covers consumer distribution), and Swank (doing educational/non-theatrical distribution for studios and other larger film distributors). Cinema Guild, First Run Features, Kino Lober, Strand, and Zeitgeist are a few all rights distributors who also focus on educational distribution.

Not every film has the same revenue potential from the same classes of distribution (i.e. some films are bound to do better on Cable VOD (documentaries usually do not do great that way). Some films are likely to do more consumer business via sales than rentals. Some do well theatrically and some not. So it is no surprise that distributors’ windowing decisions are based on where the film’s strongest revenue potential per distribution categories. Sometimes an educational distribution window becomes long and sales in that division will determine the film’s course of marketing. But if a film has a theatrical release, distributors have certain time restrictions relative to digital opportunities, so that often determines the windowing strategy, including how soon the film goes to home video.

The film being commercially available will limit the potential for educational distribution, and at the same time, the SVOD services may pay less for those rights if too much time goes by since the premiere. Hence it is critical to properly evaluate a film’s potential for each rights category.

Revenue ranges widely. On the one hand, some films may make just $1,000 a year or just $10,000 total from the services such as Kanopy and Alexander Street. On the other hand, Kanopy notes that a good film with a lot of awareness and relevance would be offered to stream to over 1,500 institutions in the US alone (totaling over 2,500 globally), retailing at $150/year per institution, over a 3-year period, and that film should be triggering about 25% – 50% of the 1,500 institutions. Licensors get 55% of that revenue. On average, a documentary with a smaller profile and more niche would trigger about 5-10% of the institutions over 3 years.

More extreme in the range, ro*co notes that its highest grossing film reached $1,000,000, but on average ro*co aims to sell about 500 educational licenses.

If the film has global appeal then it will do additional business outside the U.S. All rights and educational distributors comment that on average, good revenue is in the 5-figures range and tops out at $100,000 +/- over the life of the film for the most successful titles. The Film Collaborative, for example, can generate lower to mid 5-figures of revenue through universities as well (not including film festival or theatrical distribution). Bullfrog notes that these days $35,000 in royalties to licensors is the higher end, going down to $10,000 and as low as $3,000. For those with volume content, Alexander Street noted that a library of 100-125 titles could earn $750,000 in 3 years with most of the revenue being attributable to 20% of the content in that library. Tugg (non-theatrical (single screenings) & educational distribution) estimates $0-$10,000 on the low end, $10,000 – $75,000 in the mid-range, and $75,000 and above (can reach and exceed $100,000) on the high end. Factors that help get to the higher end include current topicality, mounting public awareness of the film or its subject(s), and speaking to already existing academic questions and interest. Tugg emphasizes the need for windowing noting the need for at least a 6-month window if exclusivity before the digital / home video release. First Run Features (an all-rights distributor that also handles educational distribution both directly and by licensing to services) had similar revenue estimates with low at below $5,000, mid-range being $25,000 – $50,000, and high also above $75,000.

Back to windowing and its impact on revenue—Bullfrog notes it used to not worry so much about Netflix and iTunes because they “didn’t think that conscientious librarians would consider Netflix a substitute for collection building, or that instructors would require their students to buy Netflix subscriptions, but [they] have been proved wrong. Some films are just so popular that they can withstand that kind of competition, but for many others it can kill the educational market pretty much stone dead.” Yet, theatrical release is usually not a problem, rather a benefit because of the publicity and awareness it generates.

Passion River explains that filmmakers should not be blinded by the sex appeal of VOD / digital distribution—those platforms (Amazon, Hulu, iTunes, Netflix) can and will wait for hotter films on their radar. An example Passion River offers is Race to Nowhere which sold to over 6,000 educational institutions by staying out of the consumer market for at least 3 years. This type of success in the educational space requires having the right contacts lists and doing the marketing. But I would say, consider the film, its revenue potential per rights category, the offers on-hand, and then decide accordingly.

Stay tuned for Parts 2 & 3, which will go into the nitty gritty details of educational distribution.

The legal information provided in this publication is general in nature and should not be construed as advice applicable to any particular individual, entity or situation. Except as otherwise noted, the views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s). This alert may be considered a solicitation for certain purposes.

Orly Ravid February 18th, 2016

Posted In: Distribution, education, Legal

Tags: Alexander Press, Amazon, Bullfrog Films, California Newsreel, Cinema Guild, classroom films, educational distribution for films, educational market for films, film distribution, film library, Films Media Group, First Run Features, Frameline Distribution, Kanopy, Kino Lorber, Netflix, New Day Films, Orly Ravid, Passion River, ro*co, Strand Releasing, The Film Collaborative, Third World Newsreel, Women Make Movies, Zeitgeist Films

Wonk/Fest 2015: Exhibition and Deliverables for the Contemporary Age

This post is part 4 of an ongoing series of posts chronicling how rapid technological change is impacting the exhibition side of independent film, and how this affects filmmakers and their post-production and delivery choices. The prior three can be found at the following links: January 2013 • August 2013 • October 2014

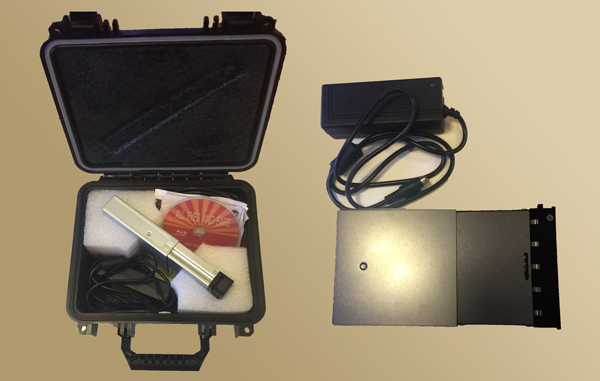

DCPs can be proprietary hard drives. Alternatively (not shown), then can look virtually identical to external hard drives

When I started this series back in 2013, a fairly new exhibition format called DCP was starting to significantly impact independent exhibition and distribution, and I was very afraid. I was sure that the higher costs associated with production, the higher encryption threshold, and the higher cost of shipping would significantly impact the independents, and heavily favor the studios.

Flash forward to today, and of course DCP has taken over the world. And thankfully we independents are still here. Don’t get me wrong…I still kinda hate DCP…especially for the increased shipping price and their often bulky complicated cases and how they are so easily confused with other kinds of hard drives…but they are a fact of life that we can adapt to. Prices for initial DCP creation have dropped to more manageable rates in the last two years, and creating additional DCPs off the master are downright cheap. And most importantly, they don’t fail nearly as often as they used to…apparently the technology and our understanding of it has improved to the point where the DCP fail rate is relatively similar to every other format we’ve ever used.

While DCPs rule on the elite level….at all top festivals and all major theatrical chains…filmmakers still need to recognize that a wide array of other formats are being requested by venues and distributors every day. Those include BluRays, ProRes Files on Portable Hard Drives, and, most significantly, more and more requests for downloadable files from the cloud.

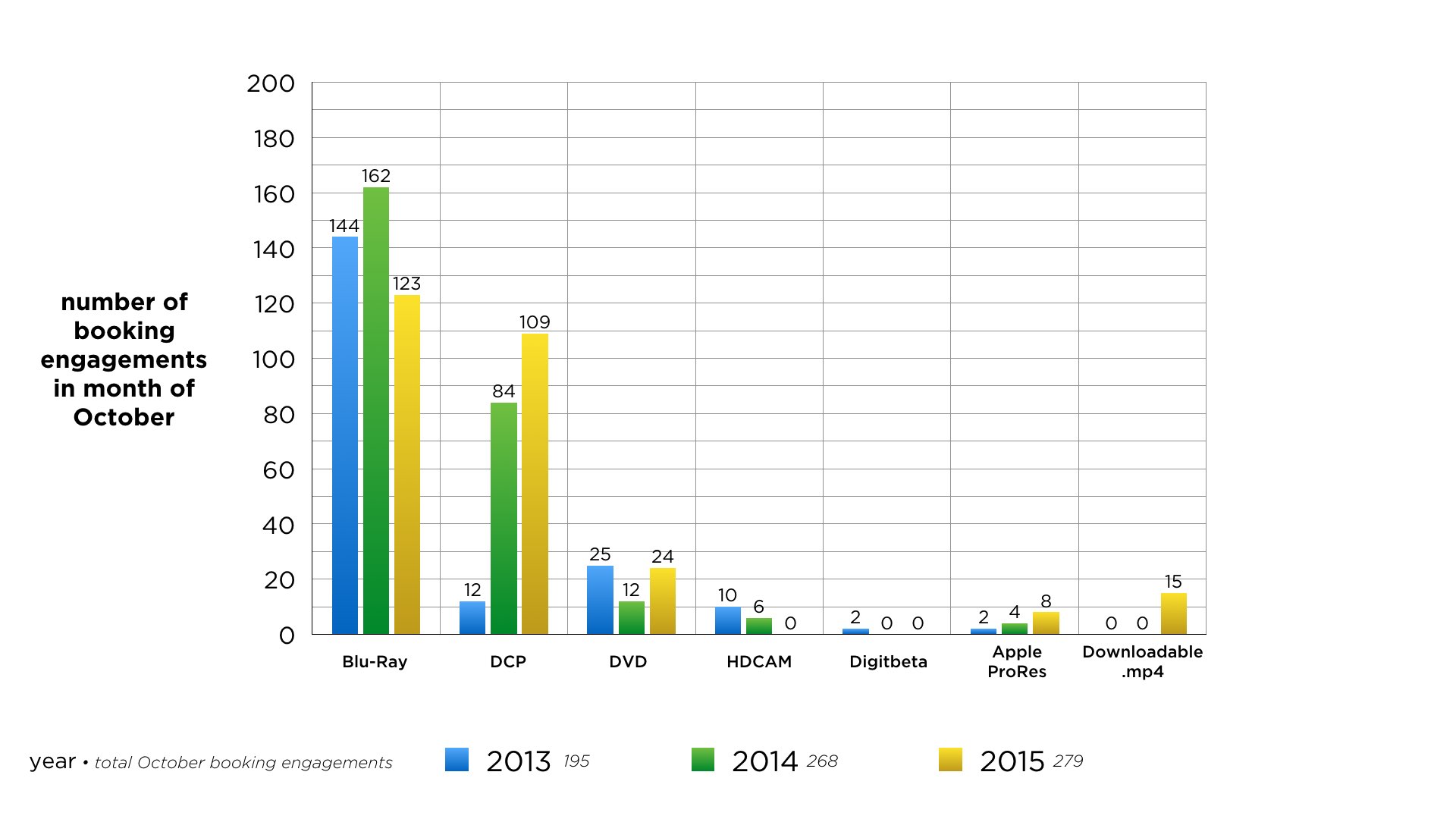

To track the evolution of formats over the last two years, please refer to the booking charts of Film Collaborative films below. Of the many things that The Film Collaborative does, one of our core services is booking our clients’ films in public venues all over the world – including everything from film festivals, traditional theatrical venues, universities, art galleries, etc. October is always the busiest month of the year…as it is the month of the year with the most film festivals. By comparing the last three Octobers, we can see quite clearly how venue deliverables have changed over the last two years.

Quick observations of the above include:

- Bluray use for exhibition has remained relatively constant over the last three years in terms of total Blurays used, although its percentage rate has declined by about 23% from last year.

- DCP use for exhibition has increased from 6.1 percent in 2013 to 31% in 2014 to 39% in 2015. It should be noted that the vast majority of high-end bookings such as top festivals or top theatrical chains require DCP now, and the vast majority of Bluray bookings are at the smaller venues.

- Digital tape formats, such as HDCAM and Digibeta, have entirely disappeared to 0. As we said in our last post to this effect….stop making these entirely!

- Requests for Quicktime files on hard drive format are on the rise…and the only reason their numbers above seem so low is because we resist booking them whenever we can—because they are an additional cost. So the 8 listed for October 2015 means in those cases we determined we had no other choice. We should discuss this further in this post.

- For the first year ever, our company is now offering downloadable vimeo links to festivals to show the film from electronic files delivered over the internet. This is a radical direction that has much to be discussed, and we shall do so later in this post. To date we are only offering these in extraordinary situations….mostly for emergency purposes.

While DCP is certainly the dominant format at major venues for now and the foreseeable future, I still maintain my caution in advising filmmakers to make them before they are needed. Nowadays, I hear filmmakers talk about making their DCP master as part of their post process, well before they actually know how their film will be received by programmers and venue bookers. Lets face it, a lot of films, even a lot of TFC member films, never play major festivals or theatrical venues, and their real life is on digital platforms. Remember that DCP is a theatrical format, so if your film is never going to have life in theatrical venues, you do not need to spend the money on a DCP.

If and when you do make your DCP(s), know that DCPs still do on occasion fail. Sometimes you send it and the drive gets inexplicably wiped in transit. Sometimes there is a problem with the ingest equipment in the venue, which you can’t control. Film festivals in particular know this the hard way….even just a year ago DCP failure was happening all the time. A lot (most) festivals got spooked, so now they ask for a DCP plus a Bluray backup. That can be a significant problem for distributors such as TFC, since it can mean multiple shipments per booking which is expensive and time-consuming. However for individual filmmakers this should be quite do-able….just make a Bluray and a DVD for each DCP and stick them in the DCP case so they travel with the drive (yes I know they will probably eventually get separated…sigh). And the Golden Rule remains….that is never ever ever travel to a festival without at least a Bluray and a DVD backup on your person. It never ceases to amaze me how many (most) filmmakers will fly to a foreign country for a big screening of their film and simply trust that their film safely arrived and has been tech checked and ready to go. If your DCP fails at a screening that you are not at…well that sucks but you’ll live. If you travel to present your film at a festival and you are standing in a crowded theater and your film doesn’t play and everyone has to go home disappointed, that, in fact, is a disaster.

As mentioned previously, more and more venues that cannot afford to upgrade to DCP projection are choosing to ask for films to be delivered as an Apple ProRes 422 HQ on a hard drive. Since this is not a traditional exhibition format, a lot of filmmakers do not think they need to have this ready and are caught unawares when a venue cannot or will not accept anything else. At The Film Collaborative, we keep a hard drive of each of our films ready to go at our lab…as mentioned we do not prefer to use them because of the extra shipping cost (DCPs are trafficked from festival to festival so at no shipping cost to us, while hard drives are not used often enough to keep them moving like this). However we do find we often need them in a pinch. So do keep one handy and ready to go out. This should not be a big deal for filmmakers, since the Apple ProRes 422 HQ spec is the most important format you’ll need for nearly all types of distribution deliveries, whether it be to distributors or digital aggregators or direct to digital platforms. So, if you plan to have any kind of distribution at all, this is a format you are almost certainly going to need. Make a couple to be safe.

Is the Future in the Cloud?

As I have touched on before, the Holy Grail of independent film distribution would seem to live in the cloud, wherein we could leave physical distribution formats behind and simply make our films available electronically via the internet anywhere in the world. This would change the economics of independent film radically, if we could take the P out of Prints & Advertising and save dramatically on both format creation and format shipping. Unfortunately today’s reality is far more complicated, and is not certain to change any time soon.

I can’t begin to tell you how often…nearly every day…small festivals looking to save on time and shipping will ask me if I can send them the film via Dropbox or WeTransfer or the like. The simple answer is no, not really. So every time they ask me, I ask them back…exactly how do you think I can do that? What spec do you need? What is the exact way you think this can work? And they invariably answer back…“We don’t know…we just hoped you’d be able to.” It is utterly maddening.

Here’s the tech-heavy problem. Anyone can get a professional-sized Dropbox these days…ours is over 5,100 gigs (short for Gigabytes, or GB) and an average 90 minute Apple ProRes 422 HQ is around 150 gigs…so that doesn’t seem like a problem. Clearly our Dropbox can fit multiple films.

The current problem is in the upload/download speed. At current upload speeds, a Apple ProRes 422 HQ is going to take several days to upload, with the computer processing the upload uninterrupted all the time (running day and night). Even this upload time doesn’t seem too daunting, after all you could just upload a film once and then it would be available to download by sending your Dropbox info. However, the real problem is the download…that will also take more than a day on the download side (running day and night) and I have yet to ever come across a festival or venue even close to sophisticated enough to handle this. Not even close. Think of the computing power at current speeds that one would need to handle the many films at each festival that this would require. And to be clear, I am told that WeTransfer is even slower.

To make this (hopefully) a little clearer…I would point out four major specs that one might consider for digital delivery for exhibition.

- Uncompressed Quicktime File (90 mins). This would be approx. 500 gigs. Given the upload/download math I’ve given you above, you can see why 500 gigs is a non-starter.

- Apple ProRes 422 HQ (90 mins). Approx 150 gigs. Problematic uploaded/download math given above. Doesn’t seem currently viable with today’s technology.

- HD Vimeo File made available to download (90 mins). Approx 1.5 – 3 gigs. This format is entirely doable—and we now make all our films available this way if needed. This format looks essentially the same as Bluray on an HD TV, but not as good when projected onto a large screen. This can be instantaneously emailed to venues and they can quickly download and play from a laptop or thumb-drive or even make a disc-based format relatively inexpensively. However, there are two major problems…a) most professional venues that value excellent presentation values and have large screens find this to be sub-par projection quality and b) this is a file that is incredibly easy to pirate and make available online. For these reasons, we currently use these only for emergency purposes…when we get last minute word that a package hasn’t arrived or an exhibition format has failed. It is quite a shame…because this is incredibly easy to do, so if we could find the right balance of quality and security…we would be on this in a heart-beat.

- Blu-Ray-Quality File (Made available via Dropbox)(90 mins). This spec would be just around the same quality as a Bluray (which is quality-wise good enough for nearly all venues) and made available via Dropbox or the like. It is estimated that this file would be around 22 – 25 gigs. This would be slow, but potentially doable according to our current upload/download calculations. This is the spec we at TFC are currently looking at…but to be clear we have NOT ever done this yet. Right now it is our pipe dream…and our plan to implement in 2016. I will follow up on this in further posts!

To conclude, where we stand now, we have yet to find a spec that is reasonably made available to venues via the internet, both in terms of quality and safety protocols…but a girl can dream.

It is critical to note that the folks I am talking to recently are saying this may NOT change in the foreseeable future…because internet speeds worldwide might need to quintuple (or so) in speed to make this a more feasible proposition. Nobody that I know is necessarily projecting this right now. And that’s a sobering prospect that might leave us with physical deliverables for quite a while now. And for now, that would be the DCP with Bluray back-up. If this changes, you can be sure we will write about it here.

But hey, maybe that Quantum Computer I’ve heard about will sudden manifest itself? Gosh, that would be cool. In the meantime…how about a long-range battery that runs an affordable electric car and is easy to recharge? That would be super cool too. We can save the world and independent film at the same time.

In the meantime…if you think I am missing the point on any of the nerdy details included in this post, or you know anything about how digital delivery of exhibition materials that I might have missed, please email me. Trust me….we want to hear from you!

Jeffrey Winter November 24th, 2015

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Film Festivals, Theatrical, Uncategorized

Tags: Apple Pro-res, BluRay, DCP, Digital Cinema Package, digital film delivery, DVD, film deliverables, film distribution, film exhibition, HDCam, Jeffrey Winter, Prints and Advertising, The Film Collaborative

Top 5 Errors Filmmakers make when doing DIY Distribution to iTunes and other Platforms

Always check with your lab or distributor to make sure their deliverable specs adhere to what is outlined below. Especially deliverables outside North America, which are sure to diverge from what is below. Much of this may apply to films who have sold to distributors, but this post is mostly aimed at those doing DIY distribution. The following also mostly applies to TVOD platforms, but may also apply to others. Again, check with your distributor/lab before you produce any deliverables.

- Know when not to do iTunes

iTunes is expensive. It will cost at least $2K to do iTunes/Amazon/GooglePlay. Think of how many people will need to rent your film at $4 (and that’s before the platform’s cut) for you to recoup that money, and then think how many more will have to do so for you to recoup your investment. Are your 1500 Facebook fans going to come through for you? Most probably won’t. A better option might be to do VHX or Vimeo on Demand and spend that money on marketing to drive people to your site. We have handled almost 50 films in the past three years via our DIY Digital Distribution Program, and the bottom line is that if you expecing people to find your film simply because it’s on iTunes while you sit back and move on to your next project, you are probably going to be in for a rude awakening. - Subtitles and Closed Captioning (part 1)

Pretty much the only way to go nowadays is to submit a textless master, with external subtitles. This can get kind of tricky, so it’s important to understand what is needed and to not expect that the lab you are working with is impervious to mistakes.- Your film is in English and has no subtitles

You will need to produce a Closed Captioning file - Your film is 100% not in English

You will need to produce a subtitle file only (Closed Captioning is not required) - Your film is mostly in English but there are a few lines (or more) of dialogue that are not in English

You will need to produce both a Closed Captioning file and what is called a Forced Narrative Subtitle file.

This “Forced Narrative” subtitle file is rather a new concept, so when you work with your subtitle lab (if you need suggestions for labs to work with, check out the ‘Subtitling, Closed Captioning and Transcription Services and Solutions’ section on the ResourcePlace tab on our website), make sure they understand that an English language forced narrative file (unlike Closed Captioning or regular subtitles) does not need to be manually turned on for territories where English is the main language, and in fact cannot be turned off in those Territories. Hence, they are forced on the screen. Together with the closed captioning, they make up a complete dialogue of your film, but they should not overlap, or else you’ll be in a situation where the same lines of text are appearing twice on the screen, and your film will be rejected.

TECH TIP: We recommend watcing your film through before you deliver with all subtitle and CC files. If your film is only in English and you only need to produce closed captioning, these files are pretty much gibberish. So ask the lab to ALSO provide you with a .srt subtitle file of the closed captioning (it’s an easy convert for them). Even though you won’t be submitting this file, you can watch it using, for example, VLC. Just make the filename of your .srt file the same as your .mov or .mp4 file, place it in the same folder, and the subs should automatically come on.

If your film has a forced narrative, keep track of your non-English dialogue…easy to do especially if your film only has a few lines of non-English. Then change the file extension .srt or .stl temporaily to .txt. This file can then be opened in any text application and eyeballed to ensure that no lines of foreign dialogue are misplaced. If you ask for a .srt conversion of your Closed Captioning file, you can do the same thing with this file to verify that these non-English lines are not repeated in the Closed Captioning. - Your film is in English and has no subtitles

- Subtitles and Closed Captioning (part 2)

Closed Captioning needs to be in .scc format. Subtitles need to be in either .srt or .stl format. But .srt file do not hold placement, so if you are making a documentary, for example, you will probably want to submit .stl. Because if you have any lower-thirds in your film, lines of closed captioning or subtitled dialogue needs to be moved to the top of the screen when lower thirds are on the screen. .srt files will appear on top of the lower thirds, and your film will be rejected.

TECH TIP: Again, watch your film back with closed captioning / subtitling to make sure your lower thirds are not blocked. - Dual Mono not allowed

Make sure the audio in your feature and trailer is stereo. This does not merely mean that there is sound coming out the L & R speakers. It means that these two tracks need to be different…and not where one side gets all the dialogue and the other gets the M&E. Think of how annoying that would be if you were in a theater. L & R tracks need to be mixed properly and outputted as such.

TECH TIP: Listen to your film before you submit, or at the very least make sure your film is not dual mono…download an applcation such as Audacity, a free program, and open your masters in that program. if the sound waves are identical for both L & R, you need to go back and redo. Don’t assume your sound guy is not infallable. - 720p not allowed

iTunes is no longer accepting 1280×720 films. In addition, they will not take a 1280×720 that has been up-rezed to 1920×1080. No one should be making movies in 720p and expect the world to cater to their film.

David Averbach September 16th, 2015

Posted In: Amazon VOD & CreateSpace, Digital Distribution, Distribution Platforms, iTunes, Vimeo

Tags: Amazon, audio on your film file, closed captioning for film file, David Averbach, Digital Distribution, filmmaker mistakes, Google Play, HD for film file, independent film, indie film, iTunes, subtitling, The Film Collaborative, TVOD, VUDU, YouTube

The Face-to-Face Teaching Exemption and Fair Use in Education Distribution: Clearing up some misconceptions

Written by Orly Ravid and Guest co-Author Jessica Rosner, who has been a booker in the educational, nontheatrical and theatrical markets since the days of 16mm. Recent projects include Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film and John Boorman’s Queen and Country.

A recent blog by Orly Ravid covered just a little bit about educational rights and distribution. This blog is intended to develop that in response to a comment about the “Face-to-Face” teaching exception. This exception defines what films can be shown for no license or permission by the producers or rights holders.

A recent blog by Orly Ravid covered just a little bit about educational rights and distribution. This blog is intended to develop that in response to a comment about the “Face-to-Face” teaching exception. This exception defines what films can be shown for no license or permission by the producers or rights holders.

The Copyright Act provides for an exception to needing a copyright holder’s permission to exhibit a copyrighted such as a film. That exception, however, is only for “face-to-face teaching” activities of a nonprofit educational institution, in a classroom. That’s why it’s called the “face-to-face” exemption.

I emphasized the key words to clarify that this exception does NOT apply to social club or recreational screenings of films or any exhibition that is not in “classroom” or “similar space devoted to instruction” where there is face-to-face instruction between teacher and student and where the exhibition relates to the educational instruction. Second, not all institutions or places of learning are non-profits. All this to say, the “face-to-face” exemption is not a carte blanche free-for-all to show any copyrighted work in any context as long as there are books around within a mile radius. This is important because educators and distributors are often unclear about what can and cannot be done under this exception to proper permission to distribute or exhibit a film without permission (which often includes a fee).

Below is some key information about the state of educational distribution in 2015 and can be done lawfully without the licensor’s permission (under the Copyright Act):

Viable options for educational distribution that involves either selling physical copies, download, or licensing streaming rights or other rights and type of rights or sales, including price points, terms, limitations, etc.

It’s important to understand that “educational sales & use” is not legal term and that educational institutions have the right to purchase any film that is available from a lawful source and use it in an actual physical class under the “face-to-face” teaching section of copyright law (discussed above). Also okay is for them to keep a copy in the library and circulate as they choose.

However, if as increasingly the case, they wish to make films available via streaming or to exhibit them outside of a class they must purchase those rights. A filmmaker or distributor can charge a higher price to an institution to purchase a DVD if they control all sales but that would be a contract situation and mean the film basically has no sales to individuals. This is done but mostly with non-feature films or ones whose market is intended to be only institutions and libraries.

Streaming rights offer a real opportunity for income for filmmaker provided they are willing to sell rights to institutions in “perpetuity” (meaning, forever). They will make more money and the institution is far more willing to purchase. Many if not most universities now want to have streaming rights on films that are going to be used in classes.

Exhibition of film at universities or educational institutions that is NOT paid for (not licensed or bought from copyright holder) – when is it legitimate (lawful) and when is it not so?

It is legal to show the film in the classroom provided it is legal copy (not duped, bought from pirate site, or taped off television). Any public showings outside the classroom are illegal. Streaming entire feature films is also illegal but streaming clips of films is not.

What is the reason or rationale for the non-lawful use?

If it is a public showing (exhibition) they (and this is usually either a student group or professor, not administration) claim “they are not charging admission” and/or that “it being on a campus” makes it “educational and in extreme cases they claim that it actually IS a class. Illegal streaming is far more insidious and involves everything from claiming streaming a 2-hour film is “fair use,” (which would justify showing it without permission) or, that somehow a dorm room or the local Starbucks is really a classroom. Bottom line: not all use of film can be defended as “fair use.” Exhibiting not just clips but a whole film is usually not lawful unless the “face-to-face” teaching exemption requirements (discussed above) are met.

There is a disconnect for these educational institutions between how they treat literature vs. cinema:

All the parties involved in streaming (legal and illegal) librarians, instructors, tech people, administrators know that if they scanned an entire copyrighted book and posted on campus system for students to access it would be illegal but some of the same people claim it is “fair use” to do with a film. I actually point blank asked one of the leading proponents of this at the annual American Library Association Conference if it was legal to stream CITIZEN KANE without getting permission or license and he said yes it was “fair use” when I followed up and asked if a school could scan and post CATCHER IN THE RYE for a class he replied “that is an interesting question.” It is important to note that “fair use” has never been accepted as a justification for using an entire unaltered work of any significant length and recent cases involving printed material and universities state unequivocally that streaming an entire copyrighted book was illegal.

Remedies to unlawful exhibition of copyrighted works for distributors or licensors:

Independent filmmakers need to make their voices heard. When Ambrose Media a small educational company found out that UCLA was streaming their collection of BBC Shakespeare plays and took UCLA to court supported by many, other educational film companies, academics reacted with fury and threatened to boycott those companies (sadly the case was dismissed on technical grounds involving standing & sovereign immunity and to this day UCLA is steaming films including many independent ones without payment to filmmakers). For decades the educational community were strong supporters of independent films but financial pressures and changing technology have made this less so. (Jessica Rosner’s personal suggestion is that when instructors protest that they should not have to pay to stream a film for a class, they should be told that their class will be filmed and next year that will be streamed so their services will no longer be needed). Orly Ravid gives this a ‘thumbs up’.

Of course remedies in the courts are costly and even policing any of this is burdensome and difficult. Some films have so much educational distribution potential that a distribution plan that at first only makes a more costly copy of the film/work available would prevent any unauthorized use of a less expensive copy or getting a screener for free etc. But not all films have a big enough educational market potential that merits putting everything else on hold. And once the DVD or digital copies are out there, the use of that home entertainment copy in a more public / group audience setting arises. As discussed above, sometimes it’s lawful, and sometimes, it’s not but rationalized anyway. It is NEVER legal to show a film to a public group without rights holder’s permission. Another viable option for certain works, for example documentaries, is to offer an enhanced educational copy that comes with commentary, extra content, or just offer the filmmaker or subject to speak as a companion piece to the exhibition. This is added value that inspires purchase. Some documentary filmmakers succeed this way. It is extremely important to make sure your films are available for streaming at a reasonable price.

Parting thoughts about educational distribution and revenue:

Overall, we believe most schools do want to do the right thing but they are often stymied when they either can’t find the rights or they are not available so get the word out.

Streaming rights should be a good source of income for independent filmmakers but they need to get actively involved in challenging illegal streaming while at the same time making sure that their works are easily available at a reasonable price. It can range from $100 to allow a school to stream a film for a semester to $500 to stream in “perpetuity” (forever) (all schools use password protected systems and no downloading is allowed). TFC rents films for a range of prices but often for $300. You may choose to vary prices by the size of the institution but this can get messy. Be flexible and work with a school on their specific needs and draw up an agreement that protects your rights without being too burdensome.

Happy distribution!

Orly & Jessica

Orly Ravid August 20th, 2015

Posted In: Distribution, education, Legal

Tags: educational distribution for films, fair use, film exhibition, film streaming rights, independent film, Jessica Rosner, Orly Ravid, The Film Collaborative

Letter to Filmmakers of the World: What Do You Want Next?

Dear Filmmakers of the World,

I write to you to ask: what do you need, what do you want?

For five years The Film Collaborative has been excelling in the film festival distribution arena and education of filmmakers about distribution generally and specifically as to options and deals. TFC also handles some digital distribution directly and through partners. And we have done sales though more on a boutique level and occasionally with partners there too, though never for an extra commission. You know how we hate extra middlemen! We even do theatrical, making more out of a dollar in “P&A” than anyone and we do a really nice job TFC has a fantastic fiscal sponsorship program giving the best rates out there.

TFC published two books in the Selling Your Film Without Selling Your Soul series and we are probably due to write a third, detailing more contemporary distribution case-studies. I got a law degree and am committed to providing affordable legal services to filmmakers and artists, which I’ve started doing.

We have never taken filmmakers rights and find that most filmmakers are honorable and do not take advantage of that. We trust our community of filmmakers and only occasionally get burned. And we have accounted without fail and paid every dollar due. No one has ever said otherwise. We do what we say we’re going to do and I am so proud of that and so proud of the films we work with and the filmmakers in our community.

So, now what? What do you, filmmakers of the world, want more of? What don’t you need anymore?

Personally, I find it staggering and sad how much information is still hidden and not widely known and how many fundamental mistakes are made all the time. Yet, on the other hand, more information is out there than ever before and for those who take the time to find and process it, they should be in good shape. But it’s hard keeping up and connecting-the-dots. It’s also hard knowing whom to trust.

TFC continues to grow and improve on what it excels at, e.g. especially festival/non-theatrical distribution. We’ve got big growth plans in that space already. My question to you is, do you want us to do more Theatrical? Digital? Sales? All of it? More books? What on the legal side? Please let us know. Send us an email, tweet, Facebook comment, a photo that captures your thought on Instagram, or a GoT raven. I don’t care how the message comes but please send it. We want to know. TFC will listen and it will follow the filmmakers’ call.

We’re delighted to have been of service for these last 5 years and look forward to many more. The best is yet to come.

Very truly yours,

Orly Ravid, Founder

p.s. our next new content-blog is coming soon and will cover educational distribution and copyright issues.

Orly Ravid July 29th, 2015

Posted In: Distribution, education, Film Festivals

Tags: film distribution, film festival distribution, Film Festivals, independent filmmakers, Selling Your Film Outside the U.S., Selling Your Film Without Selling Your Soul, The Film Collaborative

8 Legal Tips for Documentary Filmmakers

This article was originally posted on Indiewire on July 6, 2015.

From life rights to fair use, here’s what you need to know about legal issues before you make your documentary.

Over the course of my career, as both the founder of The Film Collaborative and an attorney in private practice at Early Sullivan, I have noticed a lack of understanding by filmmakers regarding the law and documentary film distribution. I hope to provide some clarity in the following blog post. But keep in mind that this post does not replace legal advice tailored to a specific film, filmmaker and distribution options/deals. Feel free to contact me with specific inquiries (contact info at the end of this post).

1. Life rights

Recently at the Edinburgh Pitch / Film Festival a filmmaker asked me a very interesting question about “life rights.” He asked whether he could prevent a media outlet from covering a story about a person or persons in a way that competed with his forthcoming documentary. He wanted to know if his having life rights to a person’s or persons’ story would make a difference. The short answer is “no;” there really is no legal protection of “life rights.”

A life rights agreement obligates the subject selling his/her life rights to cooperate with the buyer. The subject/seller is committing to helping the buyer obtain information about the subject’s life and releasing the buyer from any claims by the subject against the eventual filmmaker, and ideally also to promoting the project. These agreements, however, cannot stop a third-party from taking an interest in the story facts and covering them.

Factual information is not copyrightable. That is not to say there are no copyright theories to protect a documentary from being overtly copied. But there is no legal way to prevent a third-party from using the same true facts and expressing those facts in another work. So, one might want to keep exposure of the story under wraps, if possible, until the documentary is out, and proceed with making an excellent documentary that demands to be seen and won’t be trumped by news segments or other content.

If this issue is coming up for you and you have a concern about being overtly copied beyond the facts, then you may want to discuss with an attorney. Chances are the other party will not copy too much beyond the non-copyrightable facts for there to be legal recourse. And many jurisdictions are not so copyright-friendly to begin with. This would be especially true for documentaries where the content is non-fiction and akin to journalism.

2. Worldwide rights deals

This issue combines legal and business issues I have encountered as both an executive and an attorney. These days, with platforms such as Netflix providing international opportunities to documentary filmmakers, one should be wary of committing to international sales agents to make the “worldwide” deal. An adept U.S. sales agent or lawyer could procure and handle a great worldwide Netflix or CNN deal. A U.S. agent or lawyer might have a better shot at the worldwide deal, hence it makes sense to exhaust that option before committing to an international sales strategy. This may be of interest because often the U.S. agents’ and lawyers’ commissions and recoupable expenses are sometimes lower than an international sales companies’ (and there is often good reason for that given the breadth of territories and markets to cover on the international front).

In my experience, many American documentaries do not do well overseas and, even when they sell, they sell small. Of course there are exceptions. Point being; evaluate the potential of one big U.S. deal with lower commissions versus using international sales agents, who typically charge more. Have an experienced lawyer or producer help you carve out rights based on these possibilities (if applicable) or perhaps to help you know if and when it is appropriate to bring an international sales agent on board. Being realistic about your film’s potential based on market conditions and appropriate comparisons is critical to effective distribution and the avoidance of mistakes.

3. Educational rights vs. digital distribution

At The Film Collaborative we often notice that the more successful a film is via educational distribution and festival/non-theatrical distribution the less successful it is via traditional television and digital distribution. In short, certain less-commercial content is appealing to film festival programmers, universities, museums and other educational/non-theatrical outlets. There are, of course, exceptions to that rule and some documentaries do well across all rights and categories of distribution. These days, educational distribution involves streaming (in addition to digital master exhibition or DVD sales) but for a higher price-point than retail streaming.

Some education institutions are savvy enough not to use commercial retail copies of your film for a classroom or campus exhibition, but some do, without realizing there is a potential legal issue. If your film could do especially well on the festival circuit and through educational distribution, then you might want to delay your regular home entertainment digital and television distribution. It is also true that many film festivals will not show your film if it’s commercially available via consumer-facing platforms such as iTunes and Netflix. Most all-rights distributors do not handle educational rights either at all or as well as certain specializing educational rights distributors. Therefore, you might want to save those rights for a company specializing in “exploiting” them. The key will then be coordinating rights and windows between distributors in any given territory. Note that splitting rights is generally not an option with the majors but it is with many others and I have personally done as many as seven deals in a single territory.

4. Rights for the future

Protecting your rights for the future while satisfying the licensee (buyer/distributor) for the term of an ongoing deal can be challenging. Most deals of the past didn’t anticipate the digital age, including the Internet and streaming. There have been scores of legal battles over contracts that didn’t explicitly address digital distribution, causing parties to a deal to fight over digital rights (for example squabbling over what is included in “all technologies now known or hereinafter invented,” home video or “videogram” rights). Another even more common battle would be over whether digital rights falls into the video (VHS and then DVD) royalty or TV/broadcast.

The reason for the fight was, of course, the fact that the royalty to licensor (producers/filmmakers) or distribution percentages to distributor differ based on rights category (classification of rights). I think the degree to which one raises this as an issue should be based on the overall potential of the film in the present and the degree to which it may be evergreen or experience an uptick based on cast name recognition or genre. I like to do deals that are not only rights class/category-oriented (e.g. broadcast rights, theatrical rights), but that are broken down by revenue, and anticipate the future. You may not always have leverage to do this but if you do, it’s worth analyzing so that you do not risk having a category of rights or type of distribution that you once took for granted all of a sudden emerges as very significant and the terms are simply not in your favor and now you are locked in for 20 years. Also, you would have other protections for such a long license term if it cannot be avoided.

5. Fair use

A quick note to enlighten filmmakers about the doctrine of Fair Use, which affords one an exception to copyright protection for content used that would otherwise be protected by copyright, but only if certain factors are met. Factors include an analysis of how much of the copyrighted content at issue is used in the work; the nature and purpose of the work (for e.g. is it educational); and the effect of the use of the copyrighted work on the marketplace (e.g. will its use likely effect the potential market for the copyrighted work). This comes into play in documentaries all the time. Documentaries use new footage, photography, movie clips, archival content, etc. Fair Use is a copyright principle that allows certain otherwise copyright protected content to be used for commentary, criticism and educational purposes.

Fair Use is a legal theory and an exception to copyright that one can use a defense. It is not a license. This means that the holder of the copyright may still sue you even if you have a fair use letter from the attorney who helped you to obtain E&O insurance. So, for example, you and your attorney may believe that your use of 15-minutes of “Magic Mike XXL” in your documentary about contemporary feminism in the least expected place is “fair use,” but Warner Brothers might think otherwise. Or, maybe they’ll love it and even offer you a distribution deal. But if the copyright owner of the content perceives they lost money because of your work or is offended by how your work portrayed their work, you may be more at risk.

Of course, my example is a tad silly but the point is that when you use someone else’s copyrighted content, the degree to which you can is not always crystal clear at the outset as a matter of law. All this to say, just remember that fair use opinions are just that, opinions. A copyright holder can still sue your distributor and/or the production company entity that made the film if they feel their content has been infringed. [This assumes that you know better than to make a film under your own personal name that could expose you to significant risk of legal liability risk.] Be sure to consult an attorney BEFORE you edit your film to final cut so that you can minimize your risk of including content that might trigger a lawsuit. Lawsuits are costly and can impede distribution.

6. Price lock for licensing rights not actually licensed ahead of premiering

Well before your premiere, resolve the price for any music, footage, etc. that you are not licensing for worldwide rights in perpetuity. For example, your production budget may not allow for worldwide licensing in all rights and you may never have good reason to pay for that. So at first you license more limitedly. But it is best practice to resolve the price for any remaining rights (and for any remaining territories) so you don’t have to worry about the price being higher once the film is finished and distribution is underway. The price most often would only go up based on any success you have, and it’s better to have your licensing details resolved before you show the film and prepare it for distribution, whether DIY or via distributors.

7. Contracts are for honest people

This one is for ALL filmmakers, not just documentaries. I have seen countless disputes between people who verbally agreed to or thought they agreed to something and then argued about the agreement. It is also much more difficult to enforce an agreement not on paper. Contracts help people clarify and establish on paper what they mean (note that I have seen many convoluted contracts seemingly designed to confuse). With proper thinking, planning and good lawyering, contracts can help clarify exactly what people intend and mean by certain terms or phrases.

Contracts help force parties to think things through. Unfortunately, people fear entering into a contract or bringing up the idea of a formal agreement because they think it’s insulting or offensive. “What, you don’t think I’m honest?” Yet if one establishes from the outset that contracts are for honest people, then the other party will likely not be offended. A clear and well-drafted contract will help avoid litigation, not create it. I have seen way too many people wronged by trusting things will work out. Friends turn to frenemies over credit, money and vision issues that weren’t explicitly laid out on paper. Someone worth having on your team will not object to having a formal, non-onerous agreement. If they do, you want to analyze why.

8. Lawyer who knows distribution

Do not have your uncle, friend or family attorney who knows nothing about distribution do your legal work for your film. That is irresponsible and will harm you in the long run. Handling distribution and film licensing contracts requires a strong knowledge of the business and supporting law. Even issues around how to enforce rights via international deals and whether or not to have an arbitration provision are specific and require industry knowledge, specifically distribution knowledge. Of course, this is especially true for rights issues.

I have been asked other questions pertaining to chain-of-title, project control, financing, etc. that are beyond the scope of this post. Please feel free to reach out if you would like me to address something specifically.

Disclaimer: This article does not constitute legal advice and you should consult a lawyer about your specific situation. Also note that the images which accompany the story represent examples of films that TFC is handling for festival distribution. They are not involved in the legal concerns mentioned in the article.

Orly Ravid July 9th, 2015

Posted In: Legal

How to Win at Film Festival Roulette: Stacking Your Odds at the Top Fests

This article was originally posted on indiewire on June 26, 2015.

Be smart in organizing your priorities, do your homework and prepare for the emotional roller coaster of festivals. To help you, we’ve asked an experienced distributor to run down the numbers, so you can determine your odds.

Bryan Glick is the director of theatrical distribution for The Film Collaborative. Some of his notable releases include "I Am Divine," "Manos Sucias" and "1971". He has also worked for LAFF, AFI Fest and Sundance. Below is his take on the top festivals.

We at The Film Collaborative frequently hear from filmmakers after the fact that they regretted premiering at festival "A" and wish they had opted for festival "B." Similarly, when we ask a filmmaker why they want to premiere at a particular film festival, we rarely get an answer grounded in research.

The truth is that all the top festivals have certain types of films they gravitate towards, and all attract certain kinds of buyers looking for a particular type of product. With Sundance, Berlin, SXSW, Tribeca and Cannes behind us (and many filmmakers going into production to meet their Sundance deadline or wrapping up to apply for TIFF), we thought that now would be the perfect time to step back and look at the bigger picture of the 2015 festival landscape (including TIFF 2014).

We chose to define this list based on the number of films that screened at each festival and had not publicly stated they were being distributed before the festival lineup was announced.

The number of films listed as being acquired is to the best of our knowledge. This includes many films that have yet to go public with their distribution deals but that we can confirm from filmmakers, distributors and/or sales agents.

While we focused on a small list of top festivals, please note that major deals can come from any of a variety of festival. All that said, the following is the look at the major premiere festivals most filmmakers we meet with are pursuing.

2015 Sundance Film Festival

By the numbers:

- 74 Sundance acquisitions (including 19 for over $1 million)

- 74 of 104 films acquired

- 18 of 25 award winners acquired

Buyers: A24, Alchemy, Broad Green Pictures, Film Arcade, Fox Searchlight, Gravitas, HBO, IFC, Kino Lorber, Lionsgate, Magnolia, Netflix, Showtime, Sony Pictures Classics and The Orchard.

The lowdown: Sundance is perhaps the Holy Grail as far as buyers are concerned. Sundance is a popular stomping ground for Netflix and the all rights deals that

are much harder to come by at Cannes or TIFF. The fest is especially effective for highlighting documentaries and top notch narrative films.

The only catch is that Sundance simply isn’t an international festival. If you don’t take the all rights deal it can be much more work selling the film abroad. Since Sundance is the first big festival stop of the year, many distributors jockey for position. But if your film is not American, this might not be the festival for you. Half of the world doc/world dramatic films have yet to secure North American distribution; all but four films in the U.S . Dramatic and Documentary section have secured distribution and almost all were in six or seven figures.

As far as getting into the festival, the festival is notoriously insular. A strong majority of U.S. Competition films are backed by the Sundance Institute and/or come from Sundance alumni. Also, Sundance tends to stick to theatrical length films. You will rarely see 50-70 minute films accepted. They show a particular interest in politically-oriented documentaries.

SXSW 2015

By the numbers:

- 37 SXSW Acquisitions

- including 3 for over $1 million

- 37 of 100 films acquired

- 11 of 17 award winners acquired

Buyers: Netflix, Drafthouse Films, Roadside Attractions, Gravitas, FilmBuff, Alchemy, Vertical Films, Ignite Channel and IFC

The lowdown: SXSW is always a tricky proposition. With 145 films (20+% more than Sundance or Tribeca) presented over nine days instead of 11-12, there’s simply a lot going on. This means it is much easier to fall through the cracks. Since the festival doesn’t sell tickets ahead of time, it’s very possible nobody will show up to your screening.

However, the fact that the slate skews younger and is more adventurous often means that films have large built-in fan bases, and that there are bold discoveries that distributors can sometimes get at bargain prices. There is a reason FilmBuff and Gravitas nabbed at least eight films combined. Throw in Netflix and you have 11 titles that we can confirm going a targeted digital route.

This is the one top festival where your film is guaranteed to get screened by a festival programmer when you submit. They go out of their way to find filmmakers who are not as connected to the industry. If you don’t have industry contacts, this might be your best bet. The festival primarily programs American films and is a popular follow up to TIFF and Sundance. They also shine a light on local Texas talent.

2015 Tribeca Film Festival

By the numbers:

- 22 Tribeca acquisitions including 3 for over $1 Million

- 22 of 79 acquired

- 3 of 15 award winners sold

Buyers: A24, IFC, Saban Films, Paramount and Strand Releasing all took multiple titles

The lowdown: Tribeca screens fewer films than the other top North American fests and has a reduced schedule during the regular workweek. As the only top festival in a major U.S. industry hub, things tend to follow a more traditional trajectory.

However, we find films at Tribeca often don’t think about the long game. With summer being a slow period, many films will simply stop pursuing festivals while waiting for a deal—a strategy that tends to backfire, as more often than not they wind up forgotten.

While the narrative quality is growing, the star-driven fare tends to dominate. Some based on their star brand can get big deals, but at its heart, the fest is really about documentaries. They have a lot of character profile and political documentaries that fall under the awards bait category and frequently appeal to a more traditional indie film crowd.

As Sundance continues to narrowly define their documentary programming, Tribeca is proving to be an industry asset. This is also a great fest to go to as a North

American premiere. Frequently films that fall through the cracks at Berlin, IDFA and Rotterdam get more attention here, and also tend to be the winners on awards night. Accordingly, if you’re an American filmmaker and awards are important to you, recent history suggests that you might want to bypass this fest. Additionally (unlike SXSW), they embrace their local filmmakers far less, preferring to focus on the international power.

2015 Cannes Film Festival

By the numbers:

- 21 of 81 acquired

- 9 of 25 award winners acquired

Buyers: Alchemy, Cohen Media Group, IFC, Kino Lorber, Radius-TWC, Strand Releasing, Film Movement, IFC and Sony Pictures Classics

The lowdown: Cannes is the international behemoth and certainly being in competition is the best place to launch a film as a foreign language contender. The festival skews much more international in its programming and deal opportunities. While the U.S. distribution picture is bleaker, the rest of the world rapidly snatches up everything they can from the festival.

This is perhaps the most insider-y of the festivals. Only one film in competition was from a first-time director. Cannes frequently pulls from their own rank and file. They also show the fewest number of documentaries of any festival on the list and those are almost solely films about film/filmmakers/actors.

There are similarly few slots for genre fare. Films in the other sidebars like Directors Fortnight and Un Certain Regard are far less likely to get North American distribution when the dust settles, but can usually count on a long festival life.

Cannes, of course, is committed to films from France. However, the festival has continued to struggle in highlighting female directors.

This festival is easily the worst of the bunch for thinking outside-the-box when it comes to distribution. DIY is basically a dirty word and very few crowdfunded films get in. Distributors are also less likely to tout how much they paid for a film in press releases, which is why we do not list the amount of seven-figure deals.

2015 Toronto Film Festival

By the numbers:

- 99 TIFF films acquired (including 16 for over $1 million)

- 99 of 214 acquired

Buyers: A24, Alchemy, Bleecker, Broad Green, Image Entertainment, Lionsgate, Magnolia, Roadside Attractions, Paramount, Radius-TWC, Relativity, Saban Films, Sony Pictures Classics, Breaking Glass Pictures, China Lion, Focus World, Cinema Guild, Cohen Media Group, Film Movement, IFC, Lionsgate, Magnolia, Monterey Media, Drafthouse Films, Oscilloscope, Strand Releasing, Music Box Films, Screen Media, Saban Films, Kino Lorber and The Orchard

Now, keep in mind that TIFF was a full nine months ago. So why the relatively low numbers when compared to Sundance or even SXSW?