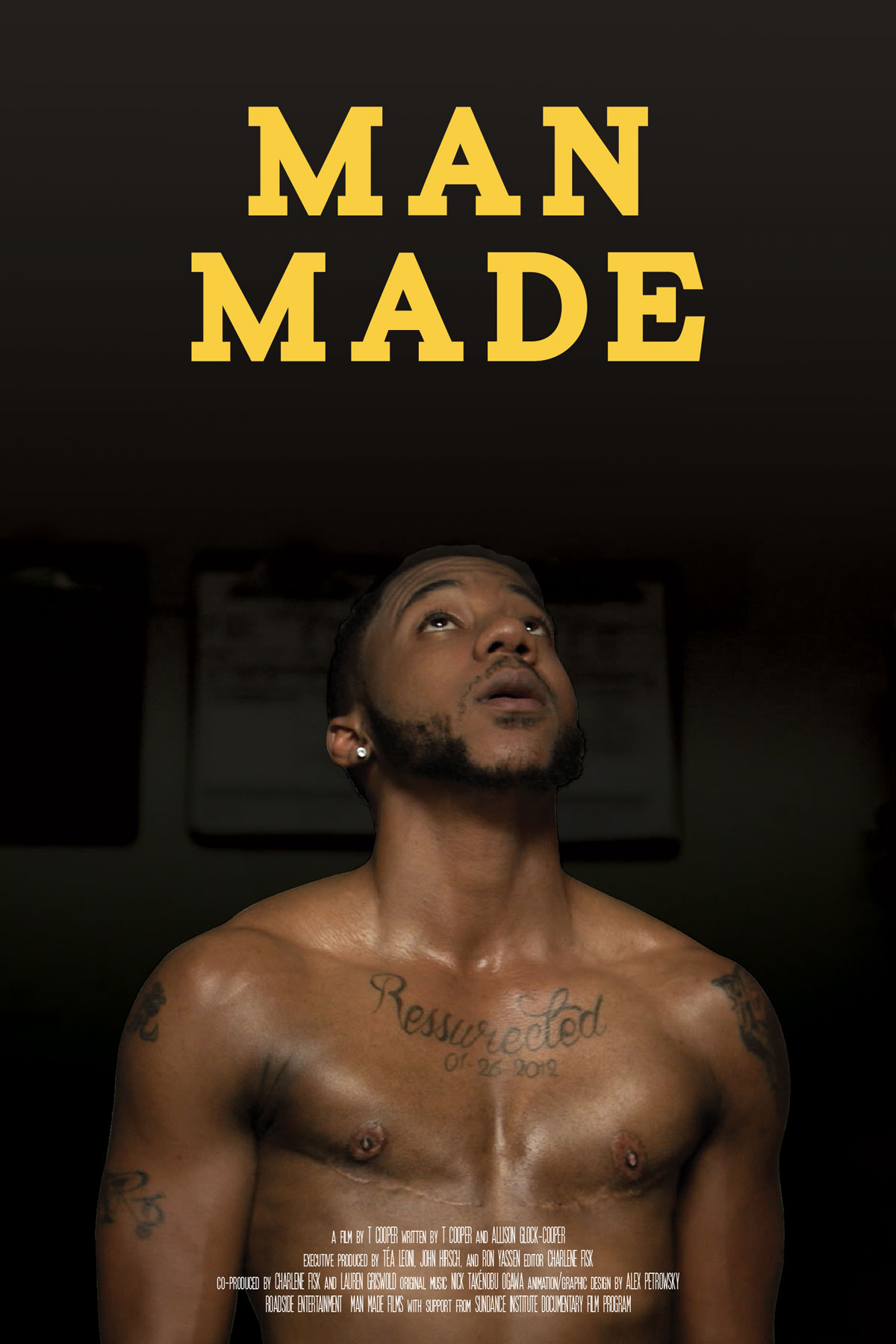

How the Director of Man Made Forged a Path for his Passion Project

January 26, 2021

T Cooper is the director of Man Made.

I made this film because I didn’t see people like me—my life, my body, my family, my identity—on the “big screen.” If I did see transgender male lives portrayed, they were often caricature, side shows, or worse—focused on what makes us (and keeps us) different and apart, as opposed to what makes us as human and recognizable as anybody else.

When I learned about Trans FitCon, the only all-trans bodybuilding competition in the world at the time, I felt compelled to document this entirely novel realm of the athletics world. But even more so, I was ignited by the creative potential of the metaphor of bodybuilding as a backdrop against which I could celebrate the trans male lives I knew—and to provide a counter-narrative to the common conceit that trans lives are miserable, or that trans people are a problem that they and their families (and society) must “overcome.”

Trans lives are not limited to our transitions, although one might be forgiven for thinking this, considering how much of storytelling around trans lives (made by cis creators) focuses solely on the particulars (and effects) of medical and social transition. I felt it imperative to show a full range of trans male life experience—from the inside looking out, rather than from the outside looking in. This trans lens is one of the things that makes Man Made unique: it is 100% trans-made trans storytelling.

Since its completion, Man Made has been embraced with uncommon passion by both trans and cis audiences alike. That is partly because of the generosity of my subjects and the trust and experience we share, and partly because Man Made reveals not just what it means to be a transgender man, but what it means to be alive during this particular cultural moment. At a time when civil rights for LGBTQIA+ people (and so many others of difference) are being attacked and rolled back at alarming rates, I believe that this project and ones like it are more vital than ever; that if we insist on continuing to tell our stories, it will be harder and harder to erase us.

Because I told the stories of my subjects’ lives like I would tell my own, in some ways Man Made *is* my story. But it is also the story of anybody who has done what it takes to become the person s/he is meant to be—despite a world that insists otherwise.

Goals

Beyond wanting to make a kick-ass, moving, and ideally beautiful movie, the goal was always for the film to reach the eyes (and hopefully hearts) of as many folks as possible, to offer a window on this small corner of a small corner of the population (trans men, most of whom are of color). To allow audiences to see the subjects’ 360-degree lives, which—again—aren’t grounded solely in their transgender identity. The dream was for the film to premiere at one of the top five festivals, so that we would have the opportunity to get it in front of potential buyers who would also recognize the importance of elevating “different” stories actually made by people of difference. But we did not get accepted into any of the “big festivals,” despite hearing from some of them that they loved the film and came very close to programming it. (But did not ultimately have space because, in some cases, there was already a transgender film that had been accepted. It was notable, at least to me, that these were trans films not made by trans filmmakers.)

If I am being honest, throughout this whole journey, I was learning as I went. Luckily, I’m a quick learner. Before beginning the filmmaking process, I wasn’t terribly informed about the multi-faceted trajectories that indie films can take as they make their way out into the big, bad world. I pretty much just began soliciting advice and guidance from colleagues and friends, as well as my management and representation (Paradigm and Mosaic, which rep me for my TV writing and producing work). So, I suppose my hopes and dreams (as I gained both filmmaking and other industry experience, like the Sundance Documentary Film Program Creative Producing Summit, which I attended during the editing stage of production on Man Made), grew to include the desire to sell the film to a streamer or network. I felt strongly (and, ultimately, wrongly, seeing as we did not ultimately place the film with a streamer or broadcast partner), that this film depicts a world that has not really been explored before in a documentary, or even, scripted, space, so I was feeling pretty hopeful all along that we could find a broadcast and/or streaming home for it.

Festival Premiere

We decided to have our world premiere at The Atlanta Film Festival. This felt felicitous to us because not only did we complete post-production in Atlanta (at the local Moonshine Post-Production), but I am located part-time there, and of course some of the film takes place in Atlanta (it’s where the bodybuilding competition is held, and where one of the four subjects is based).

The premiere was in April 2018. It was an amazingly positive experience all around. The ATLFF was extremely excited to premiere the film, and we received incredible placement at the festival (Closing Night at the largest venue/theater). There was solid word-of-mouth, and some good local and national press, and we sold out well in advance of the premiere—and also ended up taking the Best Documentary Jury Prize.

We hired a publicist (Matt Johnstone) to help with publicity around the premiere—for national (and in some cases international—United Kingdom & Canada—coverage). We received a good amount of media attention just prior to and after the world premiere, including an exclusive trailer release in Entertainment Weekly, as well as reviews in venues like The Hollywood Reporter, and features in publications like Mother Jones and Out/The Advocate.

I suck at social media, but with a little assistant aid, we did begin to build a decent social media presence, which was definitely helped by the fact that some of the main subjects and secondary subjects in the film had social media followings in the first place. With backgrounds in journalism and publishing, my wife Allison Glock-Cooper (who is also a producer and co-writer on the film) and I were able to supplement Johnstone’s press blitz, and in the end, the level of attention we received premiering at Atlanta could’ve exceeded what we might have been able to secure at one of the bigger, noisier, and more crowded festivals, where, presumably, it’s harder to get attention for smaller films. (This is, of course, ultimately unknowable.) You can find a full list of the press we received during the entire festival run and up through worldwide release/distribution (including CNN, Nightline/ABC, The New Yorker, The Guardian, and more) to the right in the sidebar.

Film Festivals

After securing the first five festivals myself (Atlanta, OutFest, Frameline, Translations, and Bentonville), I began working with the lovely and talented Jeffrey Winter at The Film Collaborative, who secured approximately 75 additional festival screenings all over the U.S. and abroad. We couldn’t have traveled that far without the help of TFC’s festival distribution shepherding, a possibility I’d only learned about (via Jenni Olson), after I started applying to festivals myself, so I was super grateful that TFC was interested in taking the helm with Man Made’s festival life.

I traveled to about a dozen of the film festival screenings, sometimes alone, sometimes with subjects of the film (including Outfest, Newfest, Inside Out Toronto, Translations, Bentonville, Cleveland, Guadalajara, and others). It was fortifying to see people from all kinds of backgrounds connect with the film in real time—no lie to say it is one of the true gifts in my life.

We were also invited to screen the film at a few company headquarters (including HBO in LA, CNN in Atlanta, and ESPN in Connecticut). The subjects were invited to join for the panels and/or talk-backs after the screenings.

Digital Distribution

We started contemplating distribution around the time the film was looking for its world premiere. The producers and executive producers (including Ron Yassen and John Hirsch at Roadside Entertainment, actor/producer Téa Leoni, along with my wife and me), were reaching out to get the film in front of potential buyers. Our sales agent (Derek Kigongo at Paradigm, who connected with the film and worked hard on its behalf) was also trying to sell the film beginning in about Feb/March 2018 and through the first six months or so of its festival run.

We had one offer for broadcast with a smaller mainstream cable network, but we waited so long that the original offer ended up going away (the network stopped acquiring docs). In the end, we went with Journeyman Pictures (UK) to distribute the film worldwide, and it was released on Amazon Prime and iTunes in September 2019.

For the film’s digital release with Journeyman, we again hired Matt Johnstone to do a few weeks of publicity surrounding the worldwide release of the film, which we specifically timed to coincide with Trans Awareness Week. Matt did some publicity and targeted outreach around that (and he secured some additional coverage as a result, most notably in The Guardian). I again spearheaded my own publicity blitz, which garnered coverage on CNN (a video segment about the film, along with a film review), as well as a segment on Nightline/ABC News, which produced a lengthy segment about Man Made, which aired a couple weeks after its release).

Our deal with Journeyman was for worldwide distribution, with educational and film festival screening rights remaining non-exclusive. Frameline is handling educational distribution in the U.S.

Journeyman has licensed the film in these territories thus far:

Cielo/Sky Italia (Italy)

Global Eagle (in-flight entertainment on New Zealand Air)

Globo (Latin America)

CNEX (Hong Kong and Taiwan)

RTP (Portugal)

UR (Sweden)

Organizational Partnerships

I sought to partner with a few social-justice oriented organizations, but nothing concrete materialized (Sylvia Rivera Law Project, Trans Lifeline, and GLAAD, who was a source of general support in the form of including Man Made in blasts, lists, social media, etc). It seems that one is so completely and constantly in the weeds at every stage of an indie film’s production that there is little spare time to pursue non-production-related opportunities and devote the kind of time required to connect with fruitful partners in a meaningful way. In retrospect, I wish I’d had a part-time PA or producer to devote resources to this area, because I think it’s a missed opportunity for a film like this in particular to reach more communities who might’ve enjoyed knowing about it.

Corporate Sponsorships

At one point we were talking to a U.S.-based international liquor and beverage company about potential sponsorship to help with finishing funds (this was something that was presented to my producing partner, Roadside Entertainment). While we were in discussions about the opportunity, the initiative changed focus, and we were lucky to receive another type of foundational support (the Sundance Documentary Film Program grant, see the next section).

Foundational, Investor, Crowdfunding Support

We received a Sundance Documentary Film Program grant for the film, which was funded by The Sundance Institute (along with the Arcus, Just Films, and Open Society Foundations). I applied to several foundations before, during, and after production, but Sundance was the only one that awarded us funding.

In addition to the Sundance Institute funding, both myself and Roadside provided funds upfront (mainly for filming). Our EP Téa Leoni offered funding as well.

I used fiscal sponsor Creative Visions (an organization I heard about through a fellow filmmaker, at a time when I wasn’t yet working with TFC and thus didn’t know there was an opportunity to use them as a fiscal sponsor). Ultimately, we took in about $35K in tax-deductible donations through fiscal sponsorship, raised through e-mail blasts, social media, and reaching out to personal friends who were invested in helping this film get finished and find its way into the world.

We also had a rough-cut screening/fundraiser at SoHo House in NYC, the costs for which were donated by a friend/supporter of the project.

Speaking Engagements and Fees

I have been to a handful of colleges and universities with the film. They pay a screening fee, as well as a small speaking fee (and cover travel). Depending on how long the visit, and how many classes I speak with, I sometimes also speak about my (literary) writing at colleges (if say, an English/Creative Writing department co-sponsors my visit with Film/Media Studies at whatever university. Before I started making films, I was—am!—a novelist and nonfiction writer).

The film was also accepted on the Southern Circuit of Independent Films, which enabled me, as the director, to travel with the film for one month, taking it to small towns and colleges/universities and other venues throughout the Southern U.S.

Ancillary

I self-funded Man Made T-shirts and sold them on the festival circuit and through the film’s website (or gave them to donors to the film). I’m pretty sure I didn’t break even on this venture—it was more to help get the word out about the film—and the T-shirts are still available on our website! (They’re soft and dope-looking.)

Revenue Analysis

Film Festival Revenue: Man Made earned a little less than $25K on the festival circuit, playing at over 70 festivals between mid-2018 and the end of 2019. One international booking scheduled in 2020 was canceled due to the pandemic.

Pretty certain we won’t ever find ourselves in the black on this project, but of course we’re hoping it has a long tail and will continue to be sold and screened in the years to come. To date, we have earned approximately $6K in our deal with Journeyman, and COVID-19 has seemed to put a serious damper on educational opportunities, though Frameline is continuing to work in this space and is in the process of getting the film onto Kanopy—they have made a few educational sales to date. (Roadside and I are equal partners, so we split everything that we recoup.)

Takeaways

In most ways I wouldn’t change much, because I feel like I learned a ton and made the best film I could make with the tools and skills and budget I had available to me at the time I was making it. I learned and grew so much, out of sheer necessity as various needs popped up throughout the entire journey, so in retrospect I can’t really envision it unfolding any other way than it did. Furthermore, the film is a success as a creative project, and is doing what I wanted it to do in that it is moving and changing people who see it in some way, even if not on as wide of a scale as we’d originally hoped.

But if I had to do it over again, there are some things I might have changed—for example, the funding/fundraising process. I probably should have tried to secure some of the private funding I ended up securing before embarking upon the type of making/filming/production that this film required—i.e., traveling to so many different parts of the country to follow these subjects. I was essentially fundraising as I went, sometimes week-to-week, trip-to-trip, which didn’t allow me to focus fully (or even primarily) on the filmmaking itself.

I would also perhaps have tried to raise or specifically dedicate funds to have at least one person helping me when I shot, whether it was a PA, or someone even nominally skilled in, for example , running audio or handling other production tasks like securing releases/locations, equipment, driving, booking travel, etc. I took one of my daughters on a day of shooting with a secondary subject in the Bronx, and even that amount of production support was invaluable—unpaid labor! Not for nothing, this daughter also composed what is for all intents and purposes the theme song for the film’s soundtrack, which is beautiful and I’m so grateful to have in the film.

I think there is good and bad that came from my shooting about 85% of this film myself. Mostly good, which comes from the intangible “magic” moments that materialized while spending so much time with the subjects, and that I was able to capture on camera because it was just me rolling wherever life took them. On the other hand, there were things I likely missed because I was effectively producing, directing, DP-ing, running audio, camera, and asking questions, setting up interviews, scheduling, etc. For most of the shoots, I did them solo (which was almost all of them, outside of the bodybuilding competitions, which co-producer Lauren Griswold at Roadside helped me with on the producing side, which was invaluable). So, the quality of some of what I shot solo was naturally lowered, and I missed things that I know would’ve been helpful to have later in edit (i.e., storytelling solutions I missed having on hand—of course we had no budget for pick-ups).

Another thing I also would do differently is not show a rough cut of the film to my major funder before it was ready to be seen by anybody outside of our production team. While they assured me that they understood the nature of a rough-cut and just hoped to offer feedback on one of their supported films, I feel like I probably exposed it too soon, before it was anywhere near ready for outside eyes, and because it was in such a rough/vulnerable state, it was perhaps more easily dismissed later as not festival-ready, which in retrospect likely could’ve hurt the film’s chances to find a broadcast or streamer sale in the long-run. Perhaps it is just my imagination—but I think I exposed my rough cut too soon.

With any film about a marginalized or underrepresented community, I feel, there can be whiff of, “yeah, but will it matter to mainstream audiences?” I think that these types of films (often social justice projects in general) very quickly get stamped as one of two things: 1) “elevated” to the status of mainstream-ready; or, more often, 2) shunted into a festival run that more directly serves the community already represented in the film.

I’m not trying to suggest that queer- or black- or trans- or women-centered festivals (and the like) are not as important, or vital to the world of filmmaking on the whole (they are likely more important), but rather, I’m suggesting that perhaps being pre-sorted into, “Oh, this is a LGBTQ film,” or that’s an “Asian film” (whatever the case may be), rather quickly sends a film down a certain path, one that doesn’t always involve the high-profile mainstream festivals, which ends up directly affecting that film’s chances for gaining the kind of attention necessary to get picked up for broadcast and/or theatrical release.

I believe that films like these (about marginalized or under-represented communities), are precisely what mainstream audiences should be exposed to more—alongside the top-selling, more requisite films about or involving celebrities or well-known subjects, historical events, crimes, etc.

As far as what I might want filmmakers to learn from this case study, it would be to take what might be helpful, and throw away the rest, like any “advice” one receives in life. The main revelation I had along the way, in fact, is that there is no single path for an indie documentary passion-project like this. What may work for one project might not work for another. I had thought that there were a few different set paths for films, and at some point you would find your film going down one them, and there would be sign-posts that help guide you, or give you some suggestions about how fast to drive, where to turn, or in other words, how to safely arrive at your destination. On my particular path, however, there wasn’t a ton of that signage. Even with some deeply-appreciated—and at times do-or-die—institutional support, and a number of instances of my reaching out for advice/help/thoughts from friends and contacts along the way, at a certain point, it just hit me that we were just going to have to figure it all out on our own, make the best decisions possible with the whatever information was available at the time.

Through the entire five-year process, I learned that each and every film literally forges its own singular path, almost as though each project has its own fingerprint. There are not going to be clear signposts, signals, or guard-rails, and if you believe in your project, you will just end up doing whatever it is you have to do at any fork in the road to get the thing made and eventually seen by people who want (and in some cases need) to see it.

There were dozens of reasons to quit making this film every single day, starting with a lack of funding, all the way down to a culture at large that fundamentally doesn’t care about the lives and people portrayed in the film. So, I suppose the main advice is: don’t give up, because there will be a million reasons to do so throughout the process. Filmmaking is a marathon—no, a triathlon—and definitely not a sprint.

TFC Takeaways

The Film Collaborative is really grateful to T Cooper for being so forthcoming, both in terms of his willingness to participate in our case study program and for providing such a heartfelt account of his journey with the film.

There are two things here that could use a bit of contextualization. The first is that we see many projects where the filmmakers are disappointed at not getting into A-list or more high-level mainstream festivals. Yet not all of them have the LGBTQ film festival circuit to “fall back on”…and we do not mean that in a pejorative sense, we simply mean that the LGBTQ festival niche can be heavily monetized and it makes no sense for a filmmaker not to avail their film of the LGBTQ festivals. Having built-in interest is a good thing because if no one knows about your film, hearts and minds will never be changed. A niche festival circuit helps build awareness, even if in the short term one feels like they are preaching to the choir. In the long term, one hopes that their film will be discovered by more of the masses than it was allowed to on festival circuit. There are scores of niche-less films that don’t get to have this.

The second is that while 2018 is less than three years ago, a lot has changed. In 2021, trans representation is more visible than ever—in movies, TV shows, state legislatures, and now in the White House, with the recent news that Biden has nominated a transgender physician as assistant health secretary. But in 2018, if you recall, many in the LGBTQ community were still using the somewhat didactic term “FTM,” something we have thankfully moved on from. And while the existence of trans men was certainly known, the awareness of the many ways that trans men can present in the world was not as great as it is just a few short years later—and the idea that there might be only one slot in a program for a trans film in mainstream festival is no longer really true. Most programmers now realize that there are many stories to tell, and although they would never program, for example, two trans bodybuilding films in the same edition of a festival any more than they would program two similar stories of any type, they are also less likely to lump trans films as a whole into a single category, as if they were checking some sort of diversity box. And hopefully, Man Made has contributed to this widening of perspective that will make future filmmakers looking to tell trans stories feel a little less pigeonholed.

TL;DR

Part of T Cooper’s success with Man Made is undoubtedly the authenticity of the storytelling: “100% trans-made trans storytelling.” Creatively, he has no regrets, although if he had to do it all over again he would have improved the way the film was funded (less on-the-fly money) so that he could perhaps not have to constantly “do it all.” He feels that would have improved the final product with more production support. In terms of his goal of reaching hearts and minds, he could not hide a bit of disappointment at being sucked into the sort-of LGBTQ film circuit rabbit hole a bit too quickly, as he questioned how many hearts and minds would be changed if one were just showing the film to folks who were already drinking the Kool Aid. However, with the help of Journeyman Pictures, and the handful of additional international broadcast deals it secured, and being able to participate in the Southern Circuit of Independent Films, the film will undoubtedly be circulated for years to come. So while the film may not ever be in the black financially, future trans stories will owe a debt of gratitute to Man Made for its pioneering spirit and authenticity.