The Implosion of Distributor Passion River… And What it Means for You

by Pat Murphy

Pat Murphy is a documentary filmmaker and editor. His latest film, Psychedelia, uncovers the history and resurgence of psychedelic research. It was sold to universities, nonprofits, international broadcasters, and the streaming service Gaia.

Passion River Films was one of those rare distributors. In an industry with plenty of shady companies, they had a reputation for honesty. Some of the most influential figures in the independent documentary distribution space referred their colleagues to them. And yet under the hood, in that nondescript office building in New Jersey, the operation at Passion River was in serious trouble. And it had been for some time.

Founded in 1998 by Allen Chou, Passion River’s catalog focused on educational documentaries, which they sold to universities, libraries, nonprofits, and the DVD/VOD market. Unlike a lot of distributors, they were flexible with filmmakers. They allowed them to put a cap on distribution expenses and reserve certain rights for themselves. I signed my film Psychedelia with them in 2021 and got the feeling that it was in good hands.

Yet for the past few years, Passion River had been withholding accounting reports and payments to filmmakers. Communication slowly dropped off and eventually went completely silent. Requests for information were ignored. And then earlier this year, they announced—in an unexpected, evasive, and self-serving manner—that they were insolvent. Hundreds of filmmakers lost many thousands of dollars, and some are still dealing with the logistical nightmare it caused for their films.

What happened at Passion River? How did it slip by undetected? We may never know. But Passion River’s collapse should serve as a stark warning to all filmmakers of the precarious nature of film distribution. It comes during a tumultuous time for the industry and the larger economy. It’s a bombshell story that demonstrates the inadequacy of systems to deal with this situation. And it shows how the hardship lands squarely on the creatives who make this industry possible.

What We Know

If you’re pressed for time, here’s a summary of the situation:

- In January, Passion River announced that they had become insolvent, and were selling the “majority of their assets” to another distributor called BayView Entertainment.

- Once filmmakers were connected with BayView, they were told that they had purchased the “assets, but not the liabilities” of Passion River.

- Passion River had been withholding accounting statements and payments to producers in 2022 and earlier, leaving producers without any record of the money they were owed. BayView said they were not responsible for these payments.

- Filmmakers had nobody to contact. Passion River abandoned its offices, shut down their phone lines and email domains, and transitioned their employees to new positions at BayView.

- The total damage in lost payments, although difficult to determine, is likely in the multiple six figures. There appears to be no accountability on the part of Passion River.

Keep reading to get the full story, as well as distribution strategist Peter Broderick’s key takeaway.

Announcing Their Insolvency

On January 31, 2023, Josh Levin (Head of Sales and Acquisitions at Passion River), sent the following note to most (but not all) of the filmmakers that had contracts with the company:

I have some news to share – the parent company of Passion River Films lost the ability to meet its obligations and has sold the majority of its Passion River assets to BayView Entertainment, LLC. BayView is a venerable, much larger film distributor with an outstanding 20+ year reputation in film distribution.

I am sure you have questions about what this transition means for you and your films. These questions can best be answered by speaking directly with Peter Castro, the VP of Acquisitions at BayView. Please email Peter at ***** to set up a call. Peter is looking forward to speaking with you.

According to their contract with filmmakers, Passion River was supposed to send accounting statements and payment 60 days after the end of each quarter. This meant that all sales that Passion River made in the fourth quarter of 2022 (October-December) were supposed to be reported and paid by March 1, 2023.

This timing was particularly unfortunate for me and my film, which had been released in Summer 2022. We secured a streaming deal with Gaia and it was released on TVOD. Gaia pays their licensing fee in two installments. So, I was waiting on the second payment ($9,750) plus all the TVOD and educational sales from my film’s release. Those payments came in the fourth quarter 2022, so I was waiting for that statement and payment to come by March 1, 2023.

Naively, I responded by asking Josh Levin about his own well-being. While I found Passion River’s work a bit sloppy and frustrating, I took Josh to be an honest broker. I was relieved to hear that he was going to work for BayView as Vice President of Sales [LinkedIn account required to view]. To me, the whole thing was portrayed as a standard acquisition. I thought that I would work with Josh as before, but this time under a new company name. I assumed my payment of over $10,000 would come from the new company.

But by the time I was able to get through to Peter Castro (VP of Acquisitions at BayView), it was already March 3, 2023. Neither my accounting statement nor my payment had arrived. My conversation with Peter turned out to be extremely unsettling. This was no ordinary acquisition. BayView had purchased the “assets but not the liabilities” of Passion River.

Yes, that’s a thing. Apparently BayView did not actually purchase the rights to our films, and therefore they were not responsible for any outstanding payments from Passion River. And they had no way of collecting that money or telling us what happened to it. We had the option to sign new contracts with them, at a less favorable split than we had with Passion River.

As for getting answers on what happened over at Passion River, such as why they became insolvent or what they did with the money that was due to us? There was no avenue to explore those questions. Josh Levin, now employed by BayView, said he was forbidden to talk about anything that happened at Passion River. Allen Chou, the president of Passion River, whom most people had never met, was elusive. The voicemail boxes at Passion River were full and their email domains would bounce.

I was devastated. And furious. Like most folks, my film was an independent labor of love over several years. What made it sting even more was the fact that Passion River did not actually secure my streaming deal with Gaia. Gaia heard about my film through my own marketing efforts, and as a good faith move towards Josh Levin, I decided to give Passion River their 25% commission on that deal.

As it turns out, I was not alone.

Finding the Others

Without any helpful information, we began finding each other through online forums like The D-Word and the Facebook group, Protect Yourself from Predatory Film Distributors [Facebook account required and one must join the group to view]. Eventually, we gathered on a private channel, so we could share information and piece together whatever we could from our own investigations and experiences.

Each film’s situation was different, but pretty much everybody reported the same experience working with Passion River: disorganized workflows, poor communication, improper accounting, missed payments, and even downright deception.

Filmmaker Jacob Bricca of Finding Tatanka said, “They were responsive at first, informing me of sales they had made and giving me regular statements showing that I was slowly paying off the charges associated with creating the DVD and distributing the film. This communication dropped off as the years went on. I finally contacted them again in mid 2022. These inquiries went unanswered. Finally, after repeated attempts to get a reply, I got a statement in early 2023 that I was owed over $1,400… I have never seen a penny from Passion River.”

Jacob was the only filmmaker I ever spoke to that had received an accounting statement for the fourth quarter of 2022. The rest of the filmmakers did not receive any accounting statements for that quarter, leaving them without a written document of what they were owed. Many reported incomplete accounting prior to the 4th quarter as well. Time and again, filmmakers were told by Josh Levin that he would “ping accounting” about their issue. However, filmmakers received no response or follow through.

While all this was happening, Passion River was still actively marketing their catalog. In March of 2023, I found an End of the Semester Sale on their website, which was active from December 1, 2022 to January 31, 2023. My film was featured prominently on the page, even though I had never received a single report of an educational sale. The fact that they would deliberately run a sale as late as December (when the sale to BayView must have been known), raises serious ethical questions.

“Passion River is not the first, or last, film company to go out of business,” said Emmy-and Peabody-winning and Oscar-nominated producer Amy Hobby. “But the lack of transparency, failed reporting, and missed payments simultaneous to continued recoupment off filmmakers’ backs is egregiously unethical.”

Attempts at a Resolution

Besides dealing with the financial fallout from Passion River, our other big question was about what to do with our films moving forward. They were still up on VOD platforms, but where was that money going? And what do we do now that we don’t have a distributor?

Director Kim Laureen, of Selfless, signed with Passion River in 2020: “Since day one I have had to chase reports and payments.” Unlike me, she was never notified of the sale to BayView. With nobody to contact about her pending payments, Kim sent a tweet out to Passion River. That got the attention of Peter Castro, VP of Acquisitions at BayView. Kim had a conversation with Peter, in which she explained why people were frustrated. Peter agreed to host a Zoom call with Kim and any other filmmaker who felt mistreated. Kim and I put out notices to the group of filmmakers about a “virtual town hall” on March 17, 2023.

Peter must have been surprised when he logged on to zoom and found dozens of angry filmmakers asking tough questions and demanding answers. Consultant Jon Reiss also joined and was instrumental in getting straight answers. The conversation went on for almost an hour and a half. We were able to confirm the following during that meeting:

- It’s unclear exactly what BayView purchased from Passion River, but it allowed them to collect revenue off of our films without a contract.

- Since BayView was currently collecting revenue on our films, they would send us payment for 2023 sales whether or not we signed new contracts with them.

- For those of us who wanted to move on to new distributors, BayView would facilitate that.

It sounds like many people ended up signing with BayView. But most of the people I’ve spoken to decided to move on to new distributors or go a DIY route without any distributor. Figuring out how to do all this and getting Allen Chou to cooperate was full of complexities over the ensuing months:

- Many distributors required an official release from Passion River. Through a collective effort led by producer Amy Hobby, Allen Chou wrote an official letter on May 9, 2023. This was his first communication to us, more than four months after the transition.

- Passion River had used an aggregator called Filmhub to upload many of our films to TVOD platforms. We were able to transition accounts with a representative there. In this scenario, the filmmaker keeps 80% of TVOD revenue, rather than giving Passion River or BayView their commission.

- BayView sent us accounting statements for Q1, as promised, on May 15, 2023.

Legal Recourse

One of the biggest revelations for me was the inadequacy of the legal system to deal with this situation. When I signed my deal with Passion River, I went back and forth on the legal language endlessly. I did everything I thought I could to protect myself and spent thousands of dollars in legal fees to do so. And when Passion River blatantly breached the contract? There was no good answer on what to do.

One avenue the legal system provides is small claims court. It’s designed to get your case heard in front of a judge without the need for an attorney. One filmmaker, who wishes to remain anonymous, decided to go this route. Their lawyer told them it was a “clear-cut case.” The filmmaker and their partner had painstakingly put together a Statement of Reasons, outlining their relationship with Passion River and what they were owed. In New Jersey, the maximum allowance is $5K.

Small claims court was on Zoom, and Allen Chou was there with his attorney, Spencer B Robbins. When it came time to present, Robbins interjected with an arbitration clause that was in Passion River’s contract, stating that any dispute between the parties should be brought in front of an arbitrator. With that, the judge threw out the case. The filmmakers tried to make a rebuttal but felt they were not given a proper chance to speak.

The filmmakers were so distraught that they decided to cut their losses and move on. “It’s why people lose faith in the justice system,” said one of them. While it’s difficult to say how much Passion River withheld from filmmakers, we can make a general estimate. Passion River had around 400 films in their catalog. So even if each film was only owed $1k that would aggregate to $400k. Almost half a million dollars. Where all that money went remains unknown. And as far as we can tell, nobody involved has been held accountable.

Key Takeaways

Here we are almost a year later. Many have expressed anger and depressed feelings around the whole situation. Writing this article has brought up a lot of emotions. But it’s also made me determined to not give in to cynicism. We need to turn this awful situation into something productive. In an attempt to do so, the following are some key takeaways from the experience.

1) The Importance of Due Diligence

“The best way that independent filmmakers can protect themselves from bad distributors is to do due diligence,” said distribution strategist Peter Broderick. “Due diligence should involve speaking to 3-5 filmmakers who are currently, or recently, in business with that distributor. The filmmaker should not ask the distributor for referrals, they should look up which films the company is working with and have confidential conversations with them about their experience. Is the distributor sending reports regularly and paying on time? Are they easily accessible to their filmmakers? Have the results matched the expectations created by the distributor? If the filmmaker isn’t comfortable sharing numbers, that’s fine. You just need a clear sense of whether working with this distributor is an opportunity or could be a disaster.”

It’s true that if I had done proper due diligence in 2021, when I was considering signing with Passion River, I probably would have avoided disaster. It seems that Passion River had been withholding payments even back then. But we also need some sort of institution where we can centralize our experience and knowledge around distributors. The issue is that everybody exists in their own silo and they don’t speak up out of fear. We need some sort of centralized way to create accountability.

2) The Filmmaker Suffers Most

It’s clear that the filmmakers bore the brunt of this entire fiasco. We were the ones who invested in our films. We are the ones who suffered the financial fallout. The employees at Passion River got new positions at BayView. Josh Levin maintains a faculty position at American University. There’s not much revenue in independent documentaries, and there is a layer of professionals who scrape whatever exists up top, leaving little to nothing for the filmmaker. So be careful where you spend your resources.

3) A Warning of What’s Ahead

The collapse of Passion River happened at an uncertain time for the industry at large. 2023 started off with the Sundance Film Festival, which saw the worst sales of documentaries in years. There will continue to be more disruptions as new technology and viewing habits change the way films are made and seen. This is also happening in a tumultuous macroeconomic environment. I would not be surprised if more distributors start to become insolvent or if they sell off their assets in the same manner Passion River did. In fact, there’s a thread on the Protect Yourself Facebook Group [Facebook account required and one must join the group to view] about filmmakers not getting paid by 1091 Pictures. If you have a contract with a film distributor, be on high alert. Stay on top of payments and reports. Ask the difficult questions. Be vigilant. If Passion River gets away with all of this, it could become a blueprint for other distributors to follow.

Thank you for reading. If you have any questions or comments, please reach out to me at pat@hardrainfilms.com.

admin October 31st, 2023

Posted In: Distribution, DIY, Documentaries, Facebook, Legal

Don’t Just “Take the Plunge” in a Distribution Deal

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To • by Orly Ravid

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next • by David Averbach

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals • by Orly Ravid and David Averbach — COMING SOON

Part 1: Know What You Are Saying “Yes” To

by Orly Ravid

We know from filmmakers the reasons they often choose all rights distribution deals, even when there is no money up front and no significant distribution or marketing commitment made by the distributor. Regardless of whether the offer includes money up front, or a material distribution/marketing commitment, we think filmmakers should consider the following issues before granting their rights.

The list below is not anything we have not said before, and it’s not exhaustive. It’s also not legal advice (we are not a law firm and do not give legal advice). It is another reminder of what to be mindful of because independent film distribution is in a state of crisis, and we are seeing a lot of filmmakers be harmed by traditional distributors.

Questions to ask, research to do, and pitfalls to avoid

- Is this deal worth doing?: Before spending time, money, and energy on the contract presented to you by the distributor, ask other filmmakers who have recently worked with the distributor if they had a good (or at least a decent) experience. Did the distributor do what it said it would do? Did it timely account to the filmmakers? These threshold questions are key because once a deal is done, rights will have been conveyed. So ask that filmmaker (and also decide for yourself) whether they would have been better served by either just working with an aggregator or doing DIY, rather than having conveyed the rights only to be totally screwed over later.

- Get a Guaranteed Release By Date (not exact date but a “no later than” commitment): If you do not get a “no later than” release commitment, your film may or may not be timely released and, if not, the point of the deal would be undermined.

- Get express specific distribution & marketing commitments and limitations / controls on recoupable expenses: To the extent filmmakers are making the choice to license rights because of certain distribution promises or assumptions about what will happen, all of that should be part of the contract. If expenses are not delineated and/or capped, they could balloon and that will impact any revenues that might otherwise flow to the filmmakers. There is a lot more to say about this including marketing fees (not actual costs, but just fees) and also middlemen and distribution fees. But since we are really not trying to give legal advice, this is more to raise the issues so that filmmakers have an idea of what to think about.

- Getting Rights back if distributor breaches, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy: Again, lots to say about this which we will avoid here, but raising the issue that if one does not have the ability to get their rights back (and their materials back) in case a distributor materially breaches the contract, does not cure it, becomes insolvent, or files for bankruptcy, then filmmakers will be left having their rights tied up without any recourse or access to their due revenues. It’s a horrible situation to be in and is avoidable with the right legal review of the agreement. Of course, technically having rights back and having the delivery materials back does not cancel already done broadcasting, SVOD, AVOD and/or other licensing agreements, nor can one just direct to themselves the revenues from platforms or any licensees of the sales agent or distributor (short of an agreement to that end by the parties and the sub-licensees)…but we will cover what is and is not possible in terms of films on VOD platforms in the next installment of this blog.

- Can you sue in case of material breach? Another issue is, when there is material breach, does the contract allow for a lawsuit to get rights back and/or sums due? Often sales agents and distributors have an arbitration clause which means that the filmmakers have to spend money not only on their lawyer(s) but also on the arbitrator. Again, there is much more to say about this, but we just wanted to raise the issue here. There are legal solutions for this, but distributors also push back on them, which gets us back to the first point, is this deal worth doing? Because if the distributor’s reputation is not great or even just good, and, on top of that, if it will not accommodate reasonable comments (changes) to the distribution deal that would contractually commit the distributor to some basic promises and therefore make the deal worth doing and protect the filmmaker from uncured material breach by the distributor, then why would you do that deal?

Filmmakers too often just sign distribution agreements without understanding what they are signing or without hiring a lawyer who knows distribution well enough to review the agreement. This is foolish because once the contract is signed and the delivery is done, the film is out of the filmmakers’ hands and they will have to live with the deal they made. If that deal was not carefully vetted and negotiated, then the odds are that it will not be good for the filmmaker. Filmmakers can make their own decisions, but we urge them to be informed.

How to best be informed:

- Get a lawyer who knows distribution

- Check out our Case Studies

- Read the Distributor ReportCard to see what other filmmakers have said about a distributor and/or find filmmakers to talk to on your own who have used them recently. If we haven’t covered a certain distributor in the DRC but one of our films has used them, just contact us. We could be happy to ask them if they’d be willing to speak with you, and, if so, make an introduction.

Part 2: Thank U (4 Nothing), Next

By David Averbach

When TFC started our digital aggregation program[1] in 2012, there was a palpable sense of possibility, that things were changing–access was opening up, and filmmakers were finally being given a more even playing field. Who needed middlemen when one could go direct [2]!?

In many ways, going direct, choosing to self-distribute, was (and maybe still is) viewed a bit like electing to be single, as opposed to the “security” of a relationship and/or a marriage. When your film gets distribution, it’s a little bit like, “They said, ‘yes!’ Somebody loves me. I don’t have to go it alone.” Less stigma, more legitimacy.

Relationships and distribution deals have a lot in common. If you are breaking up with your distributor, it can get messy. That’s why TFC Founder Orly Ravid has outlined above some of the basic concepts and things you can do with your lawyer to make sure that if you choose to do a deal, you protect yourself as you enter into a binding relationship. Like a pre-nup. So that you get to keep everything you brought with you into said relationship when you part ways.

Good News, Bad News

So, let’s say there is good news in the sense that you are able to hang on to whatever belongings you brought into the relationship.

But there’s bad news, too. Your ex is keeping all the stuff you bought together.

At least it’s going to feel like that. I know…you would rather kick your ex out and stay in your apartment. Really, I get it. But it’s not going to happen. It’s going to feel like your ex has all your stuff and won’t give it back. Because you are not going to feel grateful like Ariana; you will want someone to blame. But that’s not really fair. Because it’s more like you are both getting kicked out of the apartment and technically your partner still owns all the stuff that’s still inside, but also that they changed the locks and neither one of you can get back inside and access it. And, also, you are now homeless. Good times.

OK, let’s back up for anyone confused by the breakup metaphor: You got the rights to your film back.[3] Yay! Your film is up on all these platforms. All you want to do is keep it up on those platforms. Sorry, not gonna happen. You’re going to have to start again from scratch.

Why you have to start from scratch with most platforms when you get your rights back.

I know, you have questions. From a common-sense perspective, it makes zero sense. I’m going to go through the reasons as to why this is the case, on a sort of granular, platform-focused basis, but the answers I think say a lot about how the distribution industry is and, in many ways, has always been set up. And it underscores everything I’ve always suspected about the sorry state of independent film distribution.

I have to thank Tristan Gregson, an associate producer and an aggregation expert of many years, who was generous enough with his time to rerun questions that filmmakers have asked him over the years about salvaging an existing distribution strategy, and why, unfortunately, it is pretty much impossible.

So, let’s begin by limiting our parameters. I mentioned shared materials that were created after your deal was signed. If your distributor created trailers and artwork, I suppose that technically they own the rights, even though your distributor probably recouped their cost, but the train has left the station on those, so how likely is it that someone would go after you for continuing to use them? I would recommend making sure you have a copy of the ProRes file for your trailer and layered Photoshop files (along with fonts and linked files) or InDesign packages for your posters before things go south, because you are going to need the originals again when you start over. I’m assuming you still possess the master to your actual feature. And don’t forget about your closed captioning files.

Licensing deals (that ones that come with licensing fees) have been harder to come by for many years, but if your distributor has licensed your film to a platform, the license itself would be unaffected, so that would not have to be “recreated,” so to speak.

The rest—the usual suspects: transactional platforms (TVOD), rev-share based subscription platforms (SVOD), and ad-supported platforms (AVOD) (in other words, situations where revenue is earned only when the film is watched)—are what I’m going to be focusing on here.

Let’s say your film is up on a handful of TVOD and/or AVOD platforms. Why is it not possible for them to remain up on those platforms?

In the best of all possible worlds, couldn’t somebody simply flip a switch, change some codes, and point all the pages where your film currently lives to a new legal entity and let you continue on your merry distribution way?

But who exactly is this “someone”? They would have to have a direct contact at the platform. So maybe that’s your distributor, maybe it’s their aggregator. And is this contact at the platform the person who will do this? Probably not. It’s probably someone who deals with the tech. So now, you need to mobilize a small army of hypothetical people who are all willing to do this work for you for free. For each platform that you’re on. And don’t forget things between you and your distributor are complicated and tense right now. They are going to do you a favor to save you a few thousand bucks?

But it’s actually worse than that. You would also be assuming that Platform X, who perhaps is also trying to sell books, goods, phones and tablets, actually cares one single iota about your tiny (but fantastic) little film enough to do this for you. They do not. Despite happily taking 30-50% of your selling price for all these years. They absolutely do not.

The Nitty Gritty

I had suspected this, but I sought out Tristan for confirmation. I had only spoken previously to Tristan on a handful occasions, but he is an affable guy. Gregarious but not to the point of being garrulous. He cares. Talking to him, you get the feeling that he would go the extra mile for you if he could. Please remember this as he recites answers that he has probably given more times than he can count. His cynicism is well earned…it comes from experience.

[Note: I’ll ask and answer some of my own questions in places. Tristan’s responses will be in italics, mine will be in plain font.]

You are my distributor’s aggregator. Can’t I just work with you directly?

The answer is yes, if you start from scratch. But your distributor paid for the initial services. They paid to have it placed there. Not you.

But I made the film, and I got my rights back. Why can’t you tell Platform X to keep it up there and just change where the money should go?

Yes. I know your name is listed. But that string of 1s and 0s is associated with your distributor, not you.

It all comes back to tech. Because at the end of the day, it’s a string of 1’s and 0’s that are associated with a media file. It’s not your movie in a storefront or on a digital shelf or anything like that. In the encoding facility/aggregator world, these 1’s and 0’s are the safety net for us. We have an agreement with Party X. If Party X ends the relationship or ceases to exist, it’s written into that agreement that we pull everything down—we kill it from our archives. We’re protecting everyone. We don’t want to hold onto assets that we don’t have any relationship with. Those strings of 1’s and 0’s that go up onto a platform, and that platform has an ID tag that’s tied with the back end of the system, and that system reconciles the accounting, and the accounting reconciles with the payout. We can’t go in and just change a name on a list. That’s just not how that works.

You (the independent filmmaker with a movie) do not have a relationship, direct or indirect, with any of the platforms your distributor placed your title onto. As such, your title would not continue to be hosted at any of these outlets should your relationship with your distributor officially end. People often would say “it’s my movie, now that Distributor X is gone, just have the checks go to me.” That’s not how the platform or the aggregator ever see it, which I know is very painful for the creator who may now think they control “all their rights.”

It’s just a business entity change.

Aren’t you going to be sending me a new file anyway? Isn’t the producer card or logo going to change at the beginning the film? That’s gotta be QC’d again, in any event.

Are you telling me that if I had a 100-film catalogue, I’d have to re-QC 100 titles from scratch? That’s insane.

Let’s say Beta Max Unlimited Films had 100 titles with us and then, Robinhood Films, who is also a client of ours comes along and says, ‘Hey, we bought Beta Max Unlimited Film’s catalog, we bought all the rights to all of it. Work with us to move it over. All you guys have to do is do it on the accounting end.’ Let’s say we would be willing to do it. And let’s say we contact Platform X, we were to talk to them, talk to our rep there, and they say they are willing to relink all that media on their end, they’ll move the 1’s and 0’s over. Even then, 99 times out of 100, it never happens because you’ve got a bunch of people, and these people are kind of working pro bono on something that doesn’t really matter to them.

Just because you may think something is easy or “no work at all” doesn’t make it true, and even when it is, nobody wants to work for free. Something may be technically possible, but having all the different parties communicate and execute just never happens when nobody’s directly being paid to do the actual work.

Are you kidding me? Platform X wouldn’t move a mountain for a hundred titles?

Like, that’s nothing to them, it means nothing. What matters to them—is that stuff plays seamlessly, and it has been QC’d and approved and published. They don’t need to deviate from this because at the end of the day, it’s not going to help sell tablets and phones.

And again, we’re talking about multiple platforms. What happens if they could do this… and they get 6 out of 8 platforms to comply but the other two are intransigent? They’re going to come back to you and say, “Sorry, we tried. We hounded them 16 times, but these two won’t do it. And now you have to pay anyway to redeliver if you want to be on these two platforms.” You are going to think the aggregator is scamming you. It will not be a good look for them. Why would they want to agree to work for free with the likelihood that they will end up looking bad in the end? KISS (Keep it simple, stupid). It only makes sense to ask you to start from scratch.

Are there platforms I can actually go direct with?

You can do Vimeo On Demand on your own. (Note that for top earners [top 1%], there may be an extra bandwidth charge. You can read more about that here).

You can also do Amazon’s Prime Video Direct.

Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick…More on these later.

I thought Amazon wasn’t taking documentaries?

I believe that’s still true? However, I have access to a small distributor’s Amazon Video Direct portal. In 2021, there was a big, visible callout that said something to the effect of, “Prime Video Direct doesn’t accept unsolicited licensing submissions for content with the ‘Included with Prime’ (SVOD) offer type. Prime Video Direct will continue to help rights holders offer fictional titles for rent/buy (TVOD) through Prime Video. At this time Amazon Prime does not accept short films or documentaries.” This is June 2023. I cannot find this language anywhere in the portal. But I believe that is still the case.

What about “Amazon Prime” SVOD?

In the portal, all the territories that were once available for SVOD are still “listed,” it’s just that the SVOD column whereby you could check each one off is gone. So, no SVOD for unsolicited fiction. If you create your own Amazon Video Direct account, the territories that are available in an aggregator’s account might differ from an individual filmmaker’s account. All this seems to be moot if SVOD is not available.

So, for Amazon, it’s only TVOD?

Yes.

[Sidebar: It has usually just been US, UK, Germany, and Japan. Amazon just announced Mexico, but for this option to be available in your portal, one needs to click a unique token link that was sent out. The account I have access to received this notification. I am not certain whether this link was or will be sent out to all users. Localization is required for the non-English speaking territories in this category.]

But my distributor had gotten my documentary onto Amazon. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to once again allow it in?

Best of luck with that. Amazon is notoriously difficult and unresponsive, even with aggregators. You can try, and even if it is initially rejected, there is an appeal link somewhere in the portal that you can write in to. I have no idea if that will do any good.

My film was Amazon Prime SVOD. If I have to start from scratch with my own account, is there a way to convince them to keep it in there?

“Keeping it” is not the most accurate way of looking at the situation. It’s basically going to create a new page. And that will be controlled by the back-end in your personal account. SVOD will probably not be an option in this account. You can write in, as mentioned above, but it seems as though Amazon is trying to lessen the content glut for its Prime Video service, so I have my doubts as to whether very many people who make this request prevail.

Wait…what??! You mean that I will have a new page and therefore will lose all my reviews?

Yes and no. The old page and reviews might still be there, but “currently unavailable” to rent or buy. But on your page, the page where it is available, the reviews will not carry over. Reviews not carrying over is probably true for all platforms, but Amazon reviews are more prominent than on other platforms, so they are usually what filmmakers care about the most.

My distributor had gotten my film onto AVOD platforms Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. Do I have a better chance of getting my “pitch” accepted because it was on there before?

No.

But why? It was making some pretty good money.

You are assuming that the Tubi / Roku / Pluto TV, etc. acquisitions person is the same person who approved your film in the first place, and even then, they are going to remember your film, or are going to take the time to look up your film and see how it was doing, and also that amount of earnings you may have gotten is going to mean enough to them to matter.

If I somehow could convince someone to keep assets in place, there’s no downside, right?

Actually, that may not be true. It’s about media files meeting technical requirements, which change over time. What was acceptable yesterday isn’t always acceptable today. So when you attempt to change anything at the platform level, you risk removal of those assets already hosted on a platform.

OK, I think you get the point.

Tristan reminded me that you need to think of yourself as a cog in the tech machine.

You think all this is too cynical? Think about it…

It’s always been that way, even though we never wanted to believe it. Take the Amazon Film Festival Stars program circa 2016 as an example. A guaranteed MG. Sounded great. But on a consumer-facing level, did they make any attempt to create a section on their site/platform where discovery of these purported gems could take place? No. Did you ever stop to ask yourself why? Because at the end of the day, they didn’t really care. Any extra money they would have made was so insignificant to them that it was not worth the effort. So, they discontinued the program and blamed lack of interest.

To be fair, iTunes for many years had a very selective area for the independent genre. But it’s gone/hidden/trash now with AppleTV+. They would rather peddle their own wares than create a section that champions festival films. And remember that one, poor guy who I shall not name that you had to write to and beg in order to get your film even considered for any given Tuesday’s release? Even if you were lucky enough to be selected, if your film didn’t perform well enough it would be gone from that section by Friday morning. Or by Tuesday of the following week. All that seems to be gone now. Independent films don’t make money for them. Even though they are willing to spend $25M on CODA and $15M on Cha Cha Real Smooth.

And every so often, new platforms (like Altavod, Filmdoo, Popflick) emerge that want to change this. There are films that you actually recognize, that have played in festivals alongside yours…just…listed all together! But, have you heard of these platforms, let alone rented a film off one of them platforms or paid a monthly subscription fee? Chances are you haven’t.

This is not to blame you. But by all means, check these mom-and-pop platforms out and support your fellow filmmakers. And these are not the type of platforms that would be so hard to re-deliver to anyway. They’d probably be happy to go direct with you. It’s the big platforms that are calling cards, the ones that everyone uses, that you will want to be on even if you secretly know they are not bringing in much in terms of revenue. But either way, these platforms don’t care.

Let’s remember why aggregators exist. It’s because platforms don’t care, couldn’t be bothered, and waived their magic wand over some labs out there and said, “Now you deal with them. You be the gatekeepers.” And a whole business sector was created.

There are some distributors out there who have been around for a while that may very well have contacts at some of these platforms, but it doesn’t matter. You don’t have those connections, and chances are that they are drying up for these distributors, too.

And while this is crushing, it might also be freeing.

Tristan echoed what TFC has been saying for years: You are your own app, your own thing, most importantly, your own social media marketing campaign.

If you think about getting into bed with a distributor being like a relationship or a marriage, then your film is the kid you are raising. What kind of parent is your distributor? What kind of parent are you? Your distributor might say they will do marketing (change the dirty diapers), and then do it once or twice, but then they don’t do it again. Who is going to change those diapers it if it’s not you?

So, this relationship metaphor I am positing should not solely be directed at filmmakers who are getting their rights back. When you enter into a deal with a distributor, some filmmakers think they can now be deadbeat parents, when in reality you should co-parenting. And when your relationship with your distributor ends, you still need to raise the kid, right? It’s all on you now. And the truth is, it always was.

Notes:

[1] TFC discontinued our flat-fee digital distribution/aggregation program in 2017. [RETURN TO TOP]

[2] When we say “direct,” we mean direct to a platform, or semi-direct through an aggregator that doesn’t have a real financial stake in your distribution, as opposed to a distributor that takes rights and is (or purports to be) a true partner in your film’s distribution strategy. [RETURN TO TOP]

[3] It’s important to ensure that you have your rights back. Easiest and best way is to ask your lawyer and go through it with them both in terms of your distribution agreement, but also on a platform by platform basis. Also, to the extent that you will need to start from scratch, make sure your distributor’s assets on each platform have been removed or disabled before you attempt to redeliver them to each platform. [RETURN TO TOP]

Part 3: Goals, Goals, Goals

By Orly Ravid and David Averbach

Coming soon

admin June 8th, 2023

Posted In: Digital Distribution, Distribution, Distributor ReportCard, DIY, education, Legal

Dancing With The Real Sway: The making and releasing of “The Song of Sway Lake”

We invited longtime TFC friend Ari Gold to muse about his experience making and distributing his latest film, The Song of Sway Lake.

When I set out to make “The Song of Sway Lake,” I figured it would be a quick summer movie—designed to be shot in one location with mostly natural light—a cheap “practice movie” to get myself back into the groove of working with actors after my first film.

My co-writer Elizabeth Bull and I both loved the intellectual-romantic movies of Éric Rohmer that were set in a stunning vacation zone that provided beauty to a filmmaker who could only afford to choose shots wisely. But we also had our own American way of thinking, so of course our script became something completely different: a love triangle about family, nostalgia, theft, the lost jazz of the 1930s, and a young Russian’s passion for a much older woman. But it retained its eye towards being able to be shot very cheaply and still feel big and beautiful.

Spending summers in the Adirondacks as a kid, I was fascinated by this place that seemed to exist outside of time. On the lakes lived a declining American royalty. Along with having unfair privilege, its members were saddled with emotional paralysis. Still, I was jealous of those private lakes. For me, the “real sway” was always out of reach. Maybe I could get the life I wanted by recreating it in this movie—and traveling the world as a glamorous European style film director!

I knew that casting carefully was crucial to my success, and I figured that providing a rich and sexy role to a woman in her 70s or 80s would give me access to a neglected but glamorous movie star for a price I could afford. That’s a key with getting big actors into indies—give them chance to do something that mainstream Hollywood doesn’t.

However, low rates can lead to slow responses, and our casting director (who was also being paid a low rate) didn’t actually bother to send out my offers and inquiries. Realizing summer was rapidly approaching, we replaced the negligent casting director, and a great new one, Jessica Kelly, sprinted in to cast the film under the gun. With only weeks before the warm weather ended, we had to go by instinct, and I took the risk of casting an Irishman to play the Russian, since Robert Sheehan was the only actor of any nationality who seemed to understand the seriocomic aspects of a character we’d written based on a wild man friend from St. Petersburg. Seeking an immigrant whose adoration of a fabled America meets reality in the Sway family, a real Russian director helped me feel confident that Robert Sheehan was our man.

For the character of the broken family heir Ollie Sway, we needed an actor who could carry the shock of family trauma on his face, and found it in Rory Culkin. And for the role of the matriarch Charlie Sway, which demanded icy majesty, sensual beauty, and hidden layers of feeling, we were lucky to find Mary Beth Peil—who came in at the last minute, with a cheerful and super-pro attitude (from lots of TV and stage experience) that was able to help us through indie nights without heaters or electricity.

For the character of the broken family heir Ollie Sway, we needed an actor who could carry the shock of family trauma on his face, and found it in Rory Culkin. And for the role of the matriarch Charlie Sway, which demanded icy majesty, sensual beauty, and hidden layers of feeling, we were lucky to find Mary Beth Peil—who came in at the last minute, with a cheerful and super-pro attitude (from lots of TV and stage experience) that was able to help us through indie nights without heaters or electricity.

Every movie thinks it doesn’t have enough money. Shooting a low budget film can be crazy making, but it also can help a small crew feel like they’re all on the same team. We filmed on Blue Mountain Lake, New York, pretending that the entire lake was once a glamorous private estate, and its residents played along. The schedule was in constant flux as we danced to the ever-changing weather, which was written intricately into the plot—but never quite on the days we planned.

Plenty of adventures were there for the summer camp atmosphere. I’ll never forget rowing under the moon for a secret midnight conversation with Elizabeth Peña, who played the resentful family maid. Elizabeth asked me to consider adding a secret about her character: that she’d had an affair with the patriarch “Captain Sway” decades before. I loved it and suggested new dialog to tease her secret to the audience. “I’ll play a secret better if no one knows it,” Elizabeth said. What a rare actor to ask for less lines! Her loss is a huge one.

By the time our four weeks of shooting were up, I felt that we’d triumphed by finishing on time and on budget. I didn’t expect what happened next: my brother Ethan, who was composing the essential jazz score, suffered a traumatic brain injury; our rough-cut was politely turned down by my old standby Sundance; and my support-team moved on to other projects.

Suddenly I was sitting alone with an unfinished film and no prospects. It’s hard even for me to admit this, but I then spent several years, on and off, cutting and re-cutting the movie to figure out how to resurrect its rhythm, while my brother worked his way back to health—and finally to an ability to create the beautiful orchestral-jazz score that was essential to the story.

Music is a boobytrap that yanks us into the past, which can be intoxicating or toxic, depending how we process it. But feeling I’d orphaned the film and my own aspirations, I sunk into a depression. I didn’t have proper funds to finish the movie, without a festival acceptance to give my investors confidence; I couldn’t get into a festival without proper funds to complete it. Classic Catch-22!

Nostalgia and trauma are often linked. My characters were in it, as was I. Two days into my first silent meditation retreat, the image of a sinking wristwatch shot into my mind. I didn’t understand what it meant. When I emerged, I realized that this vision was both my life’s greatest challenge and the meaning of my film. I was linked to the three main characters not by biography, but by the struggle to let go of my mistakes. I had to look at my characters: Charlie Sway, a glamorous matriarch in her seventies, seeks her own past; her burdened grandson Ollie seeks the past’s perfection only to destroy it; and the outsider, Nikolai, wants to steal someone else’s past as his own. I was also stuck on the past, trying to relive it or destroy it or steal it.

Understanding that this sinking watch was the missing shot, I got a watch on eBay, used my iPhone to film it sinking in a local pond, did some VFX for it to match the lake water, and with this simple change and a new voiceover recorded on my bed with the noble Brian Dennehy, was able to complete the film and get it into the Los Angeles Film Festival.

Understanding that this sinking watch was the missing shot, I got a watch on eBay, used my iPhone to film it sinking in a local pond, did some VFX for it to match the lake water, and with this simple change and a new voiceover recorded on my bed with the noble Brian Dennehy, was able to complete the film and get it into the Los Angeles Film Festival.

We had great reviews–riding on 100% on Rotten Tomatoes, as long as the reviewers knew we were a tiny film—but no sales agents came to the screening. Feeling great about the reaction but scared about the finances, I accepted an invitation to be the opening night film at a festival on the island of Mallorca, Spain. Eight hundred people showed up—more great press!—and I sat with Oscar winner Paul Haggis to hear the thunderous applause. Surely this would mean I’d get the film out! But still, no one in the industry cared. Paul commiserated, and made a subtle suggestion: cut another ten minutes from the movie.

Terrified to open that can of worms, I rolled the dice with an editor friend, to see what we could do to unlock the mixed and colored cut and shave off 10% of the film. Three laborious months later, I began to swap the new cut into dozens of festivals, from Emir Kusturica’s Kustendorf festival in the mountains, to a Chinese festival, all of which were now playing and awarding the film with prizes. Still, even with Paul’s help, no distributor wanted to touch a European-style American movie about nostalgia—even with some sexy nudity and a pile of festival trophies. “Americans critics aren’t going to get it,” I was told. At one industry screening, we were told that “for a $20 million movie, it’s very gentle.” When we told them that we’d spent well below one million, people were totally confused. “But it looks so expensive!”

Realizing that for my own sanity I had to make the film available to regular people—and gamble that I could make some kind of return for my investors—we granted world-sales rights to a company called Kew Media, and worked with The Film Collaborative and The Orchard to release it in theaters in my home country. Kew made a bunch of small sales in the countries we’d had screenings, but in the States, despite massive work by our tiny team, we could barely get anyone to notice the film except a few hostile reviewers who reluctantly watched it on their laptops. The market was in a state of massive change, and these years of work got chewed into the wheels. Then, worst of all, Kew Media declared bankruptcy without having paid a single penny of my earnings. I learned the hard way that one has to be relentless about invoicing your own partners, and my team also learned the hard way that no one is to be trusted until they write you a check.

However, the movie is now available all over the world. Ever so slowly, fans are trickling into Instagram, some telling me it’s their favorite movie of all time. All my pain and nostalgia for the old world of cinema as an art form is there on the screen—and in the movie itself. I stuck to my guns and got the film into the universe, and I am finally “dancing with the real sway”—which the movie told me to do from the beginning. Sometimes our creative dreams are telling us the truth.

admin September 11th, 2020

Posted In: Uncategorized

How I Stopped Worrying and Learned to Love The Cloud: Exhibition/Distribution Technology 2020

by Jeffrey Winter

Sometimes revolutions happen with a bang, sometimes with a whimper. More often they arrive in stealth mode; one day you look up and is everything is different…just not quite the way you thought it would be.

Ever since 1) I have worked in film exhibition/distribution and 2) there has been an internet, there has been one shimmering vision on the horizon… that 1 & 2 would fully merge and the physical formats and pipelines of so-called “print” delivery would merge seamlessly into the digital data flows of the world wide web. Simply put: no more 35mm prints, no more VHS tapes, no more DVDs, Digitbetas, HDCAMs, or suitcase sized DCPs. No more trips to the post office, Fed Ex forms, tracking numbers, fretting about customs and worrying whether a snowstorm would screw up the print delivery and cancel the screening. Most importantly of course, none of the hideous and often prohibitive costs associated with all of this, that can heavily weigh down the distribution balance sheets. Simply put, something akin to distribution heaven.

Sometime in 2019, it dawned on me that after many years of twists, hiccups, re-visions and rude awakenings, the future wasn’t just the future anymore. We have finally arrived at the moment where a working draft of end-to-end digital distribution/delivery is actually in place, in rough-cut form. It’s certainly not the push-one-button, send-a-film-over email nirvana I had imagined; instead it’s a hodgepodge of file formats, myriad cloud-based services, and calculations around uploads/downloads, storage space, and piracy considerations. But it is happening and it is wonderful, with tremendous upsides and seemingly negligible negatives other than an investment of time, technical education, and reasonable precautionary practices.

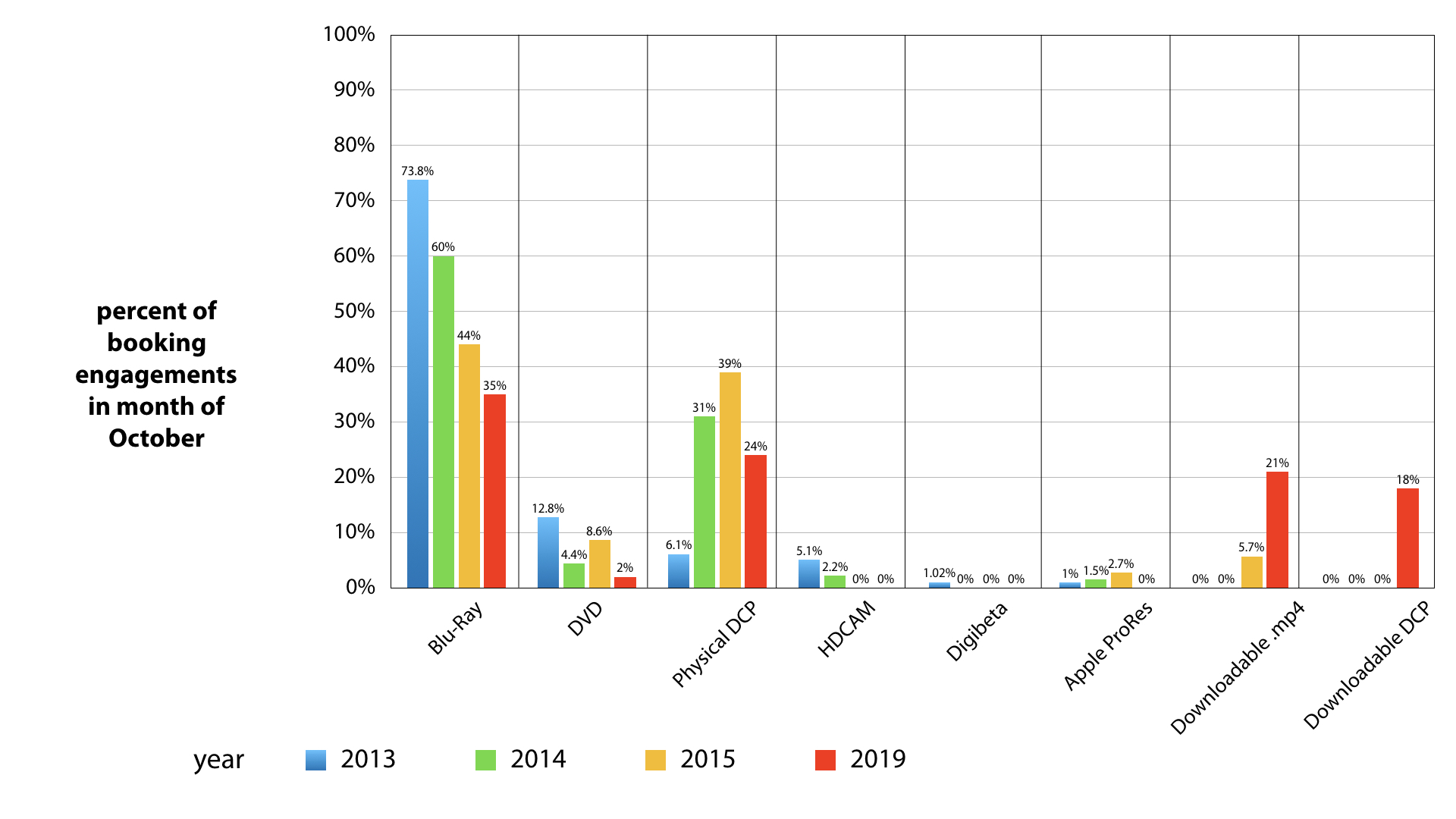

Allow me to throw some numbers at you. Every year, The Film Collaborative books and executes a few thousand screenings of our films at public venues such as film festivals, theatrical venues, universities, community centers, etc. For many years now, we have been tracking the formats we show at each booking, and analyzing the data to show how the exhibition formats are evolving. It should be noted that not all of the factors are in our control, regardless of what formats and delivery services we OFFER to a venue, THEY have to have the willingness and technical capacity to receive and show it. So, as an industry made of up many players and technical capabilities, we evolve together.

Consider the following change between bookings in October 2015 and October 2019. We typically use the month of October for purposes of analysis because it is reliably one of the busiest months of the year, so the data holds the most statistical significance.

click image to open larger

Let’s look at just 2015 versus 2019 for a moment:

Exhibition Formats: 2015 vs. 2019 (2015/2019)

total October bookings = 279/249*

Bluray: 123/83 bookings (44%/35%)

DVD: 24/4 bookings (8.6%/2%)

Physical DCP: 109/58 bookings (39%/24%)

Digital Tape Formats (HDCAM, Digibeta etc): 0/0 bookings (0%/0%)

Apple ProRes (Physical HARD DRIVE formats): 8/1 bookings (2.7%/0%)

Digital Download .MP4 FORMAT: 15/51 bookings (5.7%/21%)

Digital Download DCP Format (cloud service download): 0/43 bookings (0/18%)

*note: 9 of the Oct. 2019 bookings required no deliverables because the venue already had the film in house from a prior booking, either in physical or digital format.

Of course, in all the data, the physical versus digital delivery comparison stands out well above the rest…

- In 2015: entirely digital delivery was in its infancy at 5.7% of 279 bookings in a 31-day period.

- In 2019: digital delivery rose to 39% of all bookings in the same 31-day period.

- In 2015, digital DCP delivery was not even something we discussed, and all digital delivery was made via .mp4 downloads sent either through direct download from a website or, mostly, though DropBox links.

- In 2019, we delivered 45.75% of our total digital downloads as standard DCP files made available from an Amazon cloud based storage service, and 54.25% of all digital downloads were sent as .mp4 download links shared via Dropbox.

Looking at this dense array of formats, stats, delivery systems and storage spaces, it seems safe to revert to my pervious assertion: we have certainly not yet arrived at the push-one-button, send-a-film-over email nirvana we might once have imagined. I now currently suspect that we never will, and that was a fundamental misunderstanding of how distribution systems and broadband technology could ever work…in much the same way the flying cars in the Jetson were an absurd vision given the contemporary reality of 2019 urban traffic patterns.

And that, my filmmaking friends, is just fine…and definitely heading in a good direction!

In looking at the current data points, we clearly see that physical formats have not turned into dinosaurs, or at least not yet. A lot of that is due to residual resistance from both festivals and filmmakers, especially the most established ones. Most big film festivals, especially in the United States (we have always been the furthest behind in digital cinema in the U.S. for reasons associated with government funding structures and de-centralized infrastructure), still see digital delivery of their films as risky and substandard, and perhaps even not worth the time and energy since they can get filmmakers to deliver at their own cost. Indeed, a majority or festivals and screening venues ask for PHYSICAL BACKUPS to digital delivery…which on some level is patently absurd since once a venue downloads a film they literally have a pristine copy that can be duplicated and is just mirrored by the physical backup, which is much more susceptible to damage, loss, etc. Also…there are still plenty of smaller venues and grassroots venues, especially at universities as well as in countries with less robust broadband, that are not yet set up for internet delivery of film yet (though this is rapidly changing).

Just as significantly, many filmmakers who have been around a while still worry that internet delivery makes their films less safe, and are reticent or slow to give us full access to their pristine digital files. In analyzing the October 2019 data, it is critical to note that one well-performing film that premiered at the 2019 Tribeca Film Festival and was peaking in October festivals refused to allow us ANY access to digital files, even forbidding us from creating an emergency digital back-up to send over if the physical format failed or did not arrive! As such, the percentage of the October bookings in digital delivery would have most certainly been higher had we not been denied access to the film’s digital assets, perhaps as much as 10% higher.

It should also be noted that while digital delivery has tremendous upsides, it is also much more complicated and technical at the outset. Burning Blurays in a lab is arduous but compressing a file to decent exhibition specs and making it small enough to conform to DropBox capacities is no simple matter either. We at TFC have only been able to achieve successful digital exhibition capabilities through years of exploring technology partners and services, and amazing staffers who understand far, far more about bits and bytes than I ever will. And you’ll have to spend a lot of time prepping the films for delivery to those technology partners too.

However lest this all starts to sound frightening to filmmakers, let me list some of the ways that embracing digital exhibition has greatly enhanced our business and our sanity.

- Enormous savings in time. No, we can’t just attach a movie to an email and hit send. However, once we’ve uploaded a film once to the cloud, it’s mostly just as simple as messaging a download link to the venue (my print traffic colleague assures me that it is at least a bit more complicated to work with large files stored with Amazon Web Services). The fact that we can service a booking of four films in in Bratislava in 30 seconds by just sending an email with four links is miraculous. Multiply this by many dozens of bookings across a month, the time saved is breath-taking.

- Enormous savings in shipping costs and resources. Although the data above shows that the number of digital bookings was generally less than 50% of the total, our shipping and duping costs for the associated business quarter was actually more than 80% less than normal! At first, I was so shocked by this reduction in cost, I genuinely freaked out and assumed we had lost a huge number of our receipts! Upon closer examination, it became clear that by having digital delivery as an option, we were able to convince the venues that would have required the most expensive shipping to switch to digital receivership, and also we were able to adjust the distribution supply chain to save money in many places, especially from labs. NOTE: I generally draw the nerd/wonk line once I start using words like “distribution supply chain,” so enough about that for now. However, discussion of resources is critical…and not just in terms of saving money from duping. Obviously, any significant reduction in duping of plastics and use of carbon-based fuels associated with shipping has a tremendously positive and feel-good effect on the climate science of it all, even if I cannot offer you numbers to prove that.

- Huge reductions in stress and emergencies. One cannot overestimate the fact that now we have emergency digital backups that can resolve any sort of delivery/exhibition snafu. Throughout the entire history of film exhibition, there has always been the worry that a print will malfunction, or a delivery truck won’t arrive on time, etc. That has resulted in many a week, weeknight, or weekend filled with panicked calls and crisis management. Those days it seems, are very nearly gone, and good riddance.

To close, it should be stressed that there are lingering questions as to whether digital delivery of films makes our intellectual property less or more safe, and if filmmakers and distributors should worry how piracy will evolve to take advantage. It is important to note that for as long as there have been physical formats, especially following the decline of the all-35mm supply chain with the introduction of video, there have always been those who will figure out how to a pirate a film, regardless of format. The internet at least offers passwords, analytics, tracking, and geo-blocking that are a far cry safer than sweatshops in Asia copying DVDs smuggled out of a lab.

I, for one, have not seen any data to suggest piracy is on the rise due to digital cinema, and am open to re-evaluation should I see some. However, for now, I have learned to stop worrying so much, and hope the rest of you can see clear to join me at this exciting new juncture.

admin January 28th, 2020

Posted In: Uncategorized

Bunker 15 Films brings a modern tech twist to Indie Publicity

We invited Bunker 15, whom we worked with on the theatrical release of The Light of the Moon, to write a guest blog post for us, explaining who they are and what they did for TLOTM and other films.

Tech Entrepreneur bringing Influencer Marketing to Hollywood

Technology may be making it easier to get a film made and distributed…but how do you get your film to stand out in such a crowded marketplace? Sundance just had a mind-blowing 14,000+ applicants for their festival. Even with a theatrical release, it is difficult to capture the mind-share of viewers and build a critical mass when you have a small marketing budget and no A-list talent. To publicize their films, distribution firms and filmmakers are turning to social media campaigns to get in front of an audience because they are easy to run, relatively cheap and (hopefully) you can target a niche audience. However, in practice, again and again, social media campaigns cost more than the viewership they produce.

There might be other options. Daniel Harlow, a tech entrepreneur and founder of Bunker 15 Films, has a strategy that seems to be working—even for small indie films with limited budgets.

Background

Harlow sold his IT Consulting company (founded right out of UCLA) in 2015. After 23 years of work, 6 offices, and 300 employees, he suddenly nothing to do. He ended up going back to UCLA, this time for their post-graduate Film Studies Program for Independent Producers—mostly for fun. Harlow became fascinated with the technology changes in the entertainment industry. DVD sales had mostly gone away and theaters were primarily for large Special-Effects-driven studio blockbusters. Indies were seen at home through streaming services where piracy cut into revenues even further. “There were no answers at UCLA Film Studies for how to draw audiences to a particular film,” said Harlow. All new technology players in the film space were making their money from the Long Tail theory. Less revenue per film but a massive number of additional films will lead to more revenues overall. The game is volume. Players like Apple, Amazon and Netflix were making money but each individual film was getting a smaller and smaller share of a larger overall pie.

At his former company, Harlow ran several marketing campaigns for clients like Walmart, Nike, Macy’s, Sephora, The Gap and others. “In many situations we had exactly this Long Tail issue: an infinitely large storefront of the internet. How do you make a product stand out? Most times, we used Influencer Marketing campaigns – which are now common for the Makeup, Fashion and other industries,” said Harlow. “I went to SXSW thinking that I could find the thought leadership on this and work on real solutions, but there was no leadership on the subject. The only solution anyone proposed was the Do-It-Yourself model which I thought was only applicable to a small number of filmmakers.”

Do-It-Yourself

The DIY movement in film certainly has a lot of buzz and momentum. The Sundance Institute and other prominent institutions advocate filmmakers marketing their own films. “I had interviewed dozens of filmmakers and I just don’t know if you could possibly find a worse fit than a filmmaker with marketing. They aren’t oriented toward that and they really don’t want to do it,” said Harlow.

The DIY process for PR is fairly simple. Go online and hunt down journalists and critics yourself. Find them or their editors and email them about your film. You are bound to find some interested in watching or writing about your movie which is, by definition, more PR than you had before. And you Did It Yourself. Voila.

For a small minority of filmmakers, it works – if it fits their personality. Some producers are exhausted after the filmmaking process and would love to do something more left-brain like monetizing, marketing and distributing the film. “These types of filmmakers would probably have been involved in the business side of the film no matter what happened,” said Harlow. But it is a small group. The majority of filmmakers are artists, right-brain thinkers, and writers. Monetizing the film is too tedious for them and they probably have a queue of scripts and projects they want to move on to. The majority, once the film is finished, want to do a little press then start working on the next project. Often, these projects take so long to come to fruition that if they don’t move on quickly, it could be years before they have another finished film.

Plus, there are practical obstacles of trying to publicize your own film. Many publications have rules forbidding communicating directly with a film producer. The publication needs to be communicating with a third party to keep the article unbiased. And the sheer difficulty of chasing down critics one by one and asking them to review a film is a daunting task, particularly when coupled with the time-critical nature of the job. Film critics usually want to publish an article within a week of a film’s release. If it’s already been released, it’s ‘old news’ and if it’s not going to be released for 3 months, then don’t bother me yet, they think. That’s a narrow time window to communicate with dozens of journalists.

Thinking Forward

Despite the fact that it would be difficult for an individual filmmaker, Harlow thought that if Influencer Marketing could work in other industries, why not film? After all, film journalism already has a rich and storied history. “There must be a way to leverage the hundreds of entertainment writers out there, at least I hoped so,” said Harlow. But his initial research wasn’t encouraging. Project Lodestar did a study that surveyed 750 entertainment writers worldwide and found an overall downward trend in the coverage of Indie films. Publications had downsized their writing staff and decreased the size of their Entertainment sections, and thus they mostly needed to focus only on the biggest films. Journalists were more restricted than ever to covering only theatrically-run films in their local market.

“SXSW, UCLA and now Project Lodestar all gave off this grim picture for individual filmmakers, but I thought that what they were missing was this burgeoning space of film writers that were taking to the internet to blog on their own. More entertainment publications (especially websites) were decoupling from any given geography. And it was the geographical boundary that tied a publication to theaters in their area. The hard copy nature of old-world, established journals limited physical space available for Indie articles but these limitations also didn’t apply to website and blogs. For example, Roger Moore’s Movie Nation covers a large number of Indie films every month. So why not work with publications like that?” Harlow thought.

After several initial Beta-tests with tiny films that gave Bunker 15 Films encouraging results, it took on a big festival winner: Light of the Moon by Jessica M. Thompson. Light of the Moon was one of their first major efforts to see if the system would work. And did it! 75 Rotten-Tomatoes journalists requested to see a preview screener of the film. As expected, many of them couldn’t get their publications to publish a review about an Amazon Prime release but even some of the larger outfits did cover the film in other ways. The LA Times, for example, made Light of the Moon their VOD Pick of the Week based on Bunker 15’s outreach. The Chicago Tribune interviewed one of the actors for a piece in the paper and several of the writers wrote reviews for their blogs, many of which had huge followings. All in all, Bunker 15 Films secured 17 additional Rotten Tomatoes certified reviews for the film and a number of other pieces like the LA Times, Chicago Tribune, FilmINK in Australia, etc.

What Bunker 15 Does and How it Works

Bunker 15 doesn’t just have a large database of film and entertainment journalists but also it catalogs the films they have written about. There is information on what they have liked and disliked over time. Therefore, they can target the journalists that cover and like small Indie films. Mike Bravo, the company’s CTO, says, “There’s quite a bit of technology in place now to find entertainment bloggers and reach out to them when certain films fit their profile. We are building profiles of both critics and the publications they write for, which is complicated, because one writer might write freelance for one publication doing VOD Streaming movies but might only cover theatrical films for another publication. Plus, writers move around and change publications all the time. We are also trying to build resources for the critics themselves so the critics have an interest in being in contact with Bunker 15,” Bravo says.

“The key for us really is finding that subset of critics that are going to be interested in a particular film and that’s not real easy. Each journalist and publication has geographical and theatrical constraints, genre interests, timing issues… there are a lot of variables but we try to find the journalists that are really into a particular film or genre and focus there,” Harlow says.

The results have been amazing. Turns out that critics really want to watch Indies and like them when they watch them. It’s all about expectations. If it’s a small film, the critic will judge it on its own merit, not by its production value or special effects budget.

Critical reception for many of their films, like Light of the Moon, Stay Human, A Boy Called Sailboat, and others has been overwhelmingly positive. “Not every film we work with has a fantastic reception among the critics but our ability to get to journalists that do like Indies (as opposed to those whose expectations are met only by large Studio efforts) can make a big difference,” says Harlow.

The Future of Bunker 15 Films

“We see ourselves moving into other industries eventually because the same macro-trends that are affecting film are also at work with literature and music. The technologies that allow them to be created and distributed have resulted in an explosion of content for the average consumer to wade through with little except Influencers and reviewers to help choose among everything coming at them each day. But for now, we continue to build out tools and content for entertainment journalists and focus on film,” he says.

“As we move forward, I think the ground will shift in our favor,” say Harlow. The MN Star Tribune now has a Rotten Tomatoes certified movie critic reviewing VOD releases for the week. The LA Times is expanding their coverage of Streaming films and so is the New York Times. In addition, many publications are treating Netflix Originals in the same category as Theatrical releases. Harlow continues, “The trend to cover more and more VOD Streaming releases will increase which will put more journalists within our reach for our Indie films.” If it’s working now, then it’s safe to say it will work better as time goes on.

About Bunker 15 Films

Bunker15’s smart-tech Publicity Engine helps find the right journalists to promote your film (VOD or Theatrical). Even VOD releases can earn Press. Every film deserves to find its audience. Whether you have a small film with a limited theatrical release or you have a Straight-to-VOD feature, they can reach out to the journalists that are interested in your story.

admin April 15th, 2019

Posted In: Uncategorized

What Nobody Will Tell You About Getting Distribution For Your Film; Or: What I Wish I Knew a Year Ago.

By Smriti Mundhra

Smriti Mundhra is a Los Angeles-based director, producer and journalist. Her film A Suitable Girl premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in 2017 and is currently playing at festivals around the world, including Sheffield Doc/Fest and AFI DOCS. Along with her filmmaking partner Sarita Khurana, Smriti won the Albert Maysles Best New Documentary Director Award at the Tribeca Film Festival.

I recently attended a panel discussion at a major film festival featuring funders from the documentary world. The question being passed around the stage was, “What are some of the biggest mistakes filmmakers make when producing their films?” The answers were fairly standard—from submitting cuts too early to waiting till the last minute to seek institutional support—until the mic was passed to one member of the panel, who said, rather condescendingly, “Filmmakers need to be aware of what their films are worth to the marketplace. Is there a wide audience for it? Is it going to premiere at Sundance? Don’t spend $5 million on your niche indie documentary, you know?”

Immediately, my eyebrow shot up, followed by my hand. I told the panelist that I agreed with him that documentaries—really, all independent films—should be budgeted responsibly, but asked if he could step outside his hyperbolic example of spending $5 million on an indie documentary (side note: if you know someone who did that, I have a bridge to sell them) and provide any tools or insight for the rest of us who genuinely strive to keep the marketplace in mind when planning our films. After all, documentaries in particular take five years on average to make, during which time the “marketplace” can change drastically. For example, when I started making my feature-length documentary A Suitable Girl, which had its world premiere in the Documentary Competition section of this year’s Tribeca Film Festival, Netflix was still a mail-order DVD service and Amazon was where you went to buy toilet paper. What’s more, film festival admissions—a key deciding factor in the fate of your sales, I’ve learned—are a crapshoot, and there is frustratingly little transparency from distributors and other filmmakers when it comes to figuring out “what your film is worth to the marketplace.”

Sadly, I did not get a suitable answer to my questions from the panelist. Instead, I was told glibly to “make the best film I could and it will find a home.”